When protesters in Burkina Faso’s capital last Thursday burned the parliament to the ground and forced President Compaoré’s resignation the following day, some there and in other sub-Saharan African nations immediately dubbed the uprising the “Black Spring,” in comparison to the ethnically-labeled Arab Spring of North Africa and the Middle East. They were hoping that Black Africans would have their own moment to try to throw out dictators in a big wave.

Francophone (French-speaking) Twitter was flooded with the phrase “printemps noir” — literally “Black Springtime” — used alongside and in comparison to “printemps arabe,” the French term for the Arab Spring uprising that kicked off in Tunisia in December 2010. Tunisia, like Burkina Faso, was formerly part of the French colonial system, and Tunisian dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali rose to power in November 1987 just weeks after Blaise Compaoré seized power in Burkina Faso, so the comparisons are natural.

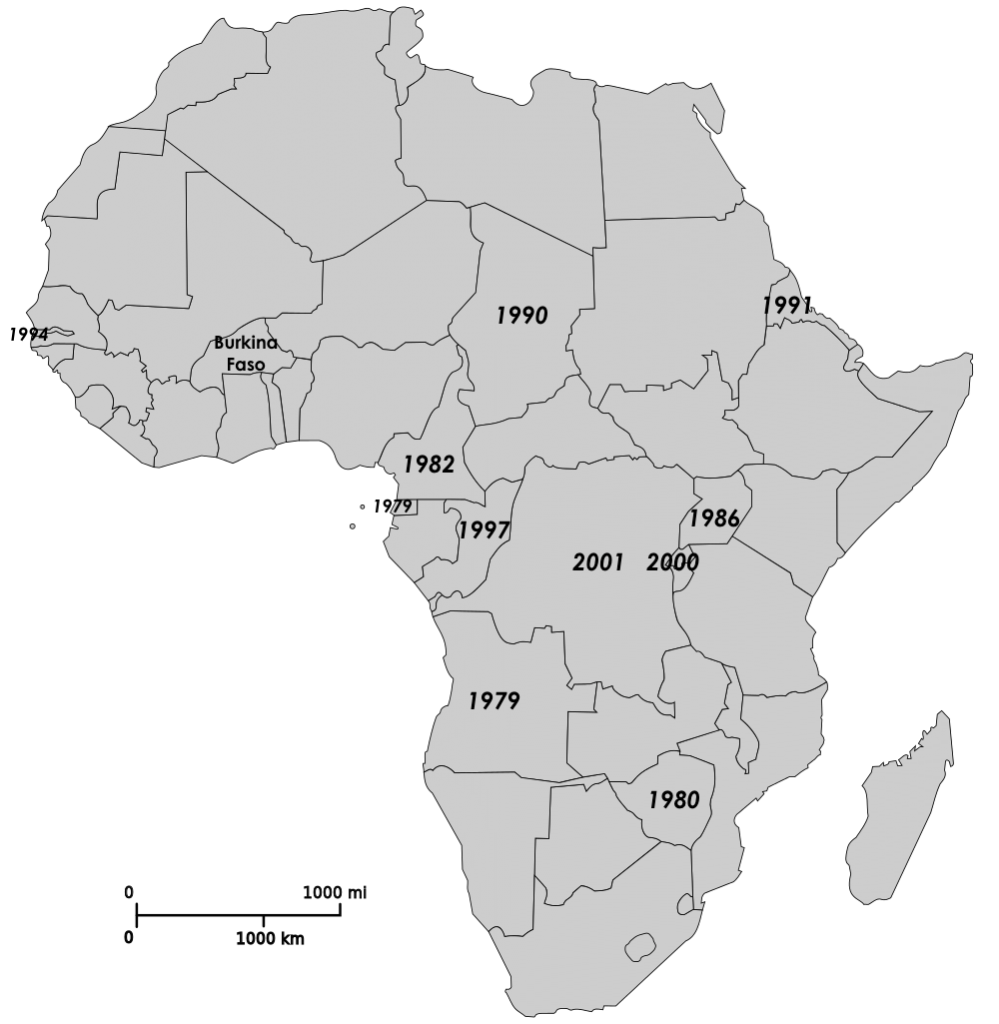

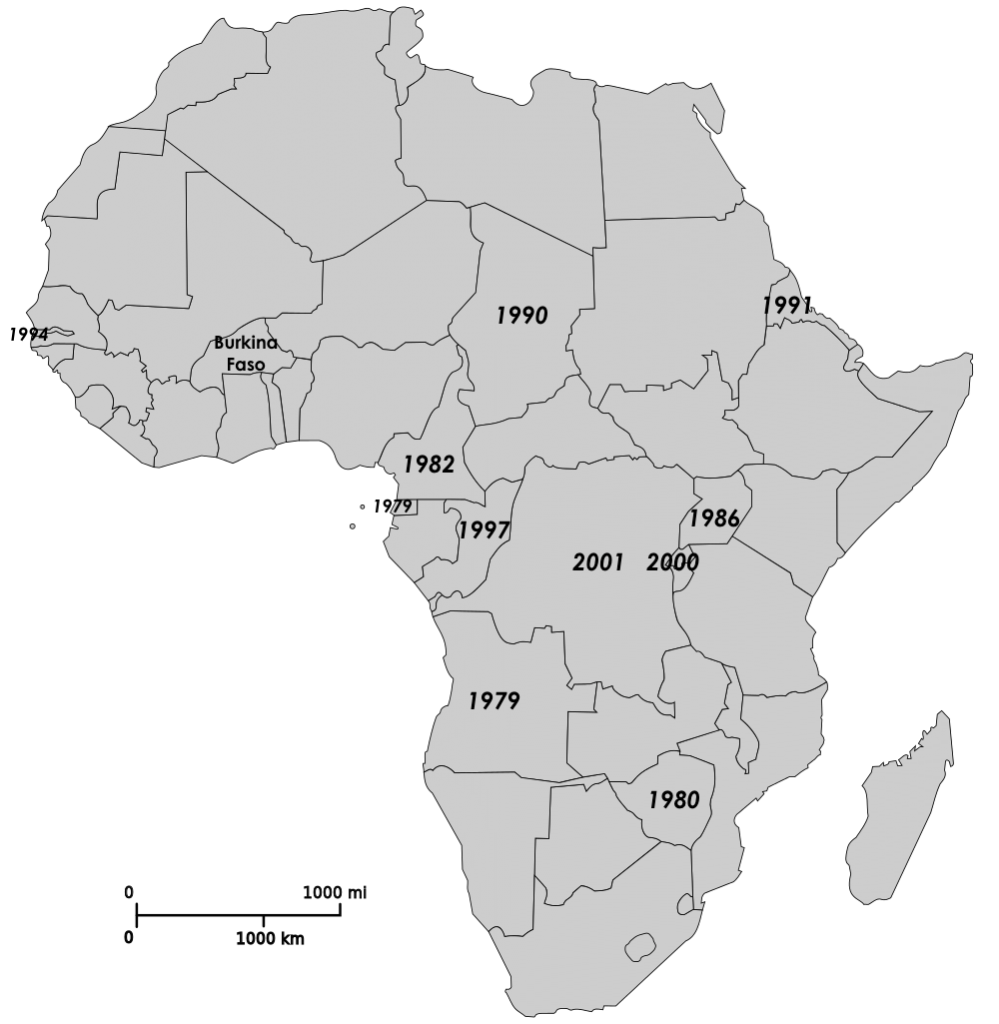

Moreover, there are a number of other sub-Saharan African leaders (see map at bottom) who have been in office either nearly as long or significantly longer, who might be vulnerable to a domino effect like that seen in North Africa, while others with authoritarian leanings from the post-Cold War period who might be looking to extend their rule unconstitutionally or excessively. In the latter category, Rwanda, DR Congo, Republic of Congo, Chad, etc. In the former, Cameroon’s Paul Biya has been president since 1982 (and remains entrenched despite recent mounting spillover chaos from the Nigeria insurrection); in Equatorial Guinea, one of Africa’s two “1979 Presidents” (now the world’s longest-serving non-monarch leaders) has passed the 35 year mark and shows no sign of stopping; Uganda; Zimbabwe; etc.

In sum, Reuters reports:

[…] several “Big Men” rulers are approaching the end of their mandates amid concerns that they may try to cling to power by changing their countries’ laws.

Particularly in West Africa, some opposition supporters believe they can thwart such ambitions in the same way that Arabs in North Africa forced out the rulers of countries such as Tunisia and Egypt in 2011.

But how likely is that really? For one thing, it’s still not clear yet that Burkina Faso will successfully move from a military-led “transition” government currently in power toward democratic, civilian rule.

For another, it’s distinctly possible that this is an outlier that won’t be replicated domino-style, as in North Africa and the Middle East. On the one hand, Burkina Faso isn’t all that similar to other countries that might appear to be primed for mass uprisings:

The poor, cotton-producing state south of the Sahara desert already had a tradition of street protest and military-supported social uprisings. Marxist military captain Thomas Sankara led a popular revolution in 1983 inspired by Fidel Castro’s rise to power in Cuba in the late 1950s.

[…]

However, they face more firmly entrenched rulers and elites than did the protesters in Burkina Faso. Crucial to the success of Compaore’s overthrow was army sympathy with the disgruntled masses, following a 2011 military revolt over unpaid bonuses.

[…]

By contrast, presidents of wealthy oil-producing states, such as Angola’s Jose Eduardo dos Santos or Equatorial Guinea’s Teodoro Obiang Nguema [both 35 years in power], can use state resources to grease the wheels of political patronage and invest in the loyalty of their military hierarchies.

Plus, they have the added advantage of seeing this coming from farther off, in part by having watched the missteps and failed suppression of the Arab Spring uprisings in some countries — as well as the far more “successful” suppression or avoidance tactics employed by some of the rulers of potential Arab Spring countries, such as the Kingdoms of Morocco and Jordan.

On the other hand, sometimes these things have a habit of getting away from you and beating expectations:

But veteran leaders cannot underestimate their increasingly vocal young urban populations. Millions of youngsters are coming onto the labour market and if their hunger for jobs, equality and a greater political say is not met, this could be a demographic time bomb for those who are reluctant to go.

After all, most observers (me included, to be sure) didn’t expect the Tunisian revolution’s example to explode so quickly and strongly into Libya, Egypt, or Yemen — and result in the collapse of their strongmen.

A partial map of the years that Sub-Saharan African strongmen took office, in relation to Blaise Compaoré’s 1987 coup in Burkina Faso. (Map labels by Arsenal For Democracy.)

As the BBC

As the BBC