Past Arsenal For Democracy co-host Greg on the significance of today’s trademark ruling against Washington’s NFL team.

This morning, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) ruled in favor of Amanda Blackhorse, a psychiatric social worker and Navajo woman who, along with four other Native Americans, challenged the “Washington Redskins” trademark in court this Wednesday. The ruling cancels six federal trademarks registered by the professional football franchise from Washington, D.C. between the late 1960s and 2000.

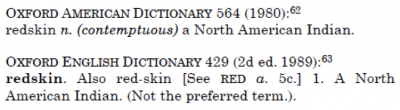

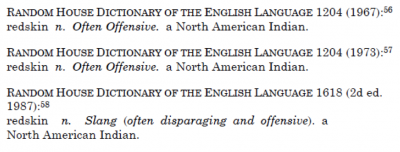

Blackhorse, et al. challenged the trademark under Section 2(a), 15 U.S.C. §1052(a) which prevents the issuance of trademarks that “may disparage or falsely suggest a connection with persons, living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, or bring them into contempt, or disrepute.” That the name “redskins” is disparaging has been fairly well established over the past several decades–the USPTO had already cancelled the “redskins” trademark in 1992 because of its disparaging nature, a decision that was only reversed in federal appeals court because of a technicality–and does not warrant reexamination here (you either get it or you don’t). More telling are the USPTO’s selections from this enormous evidence body of evidence:

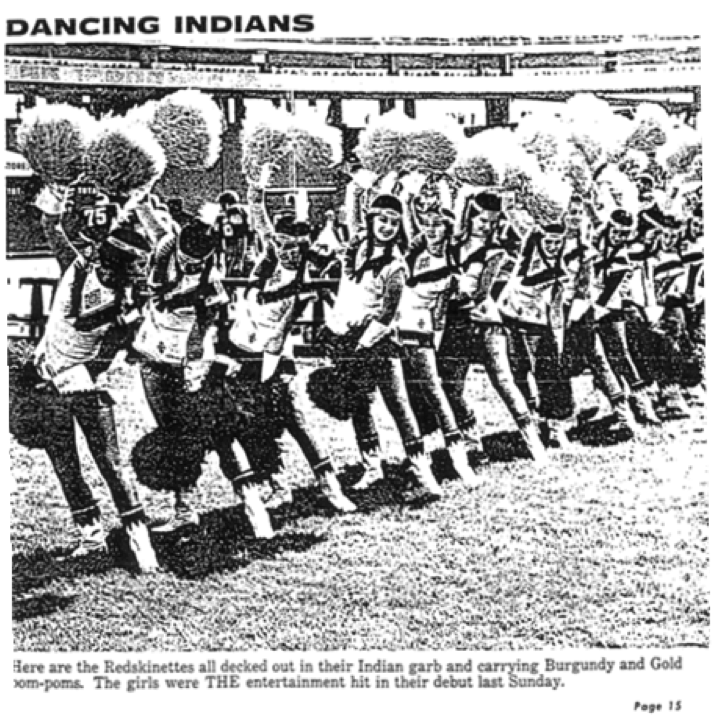

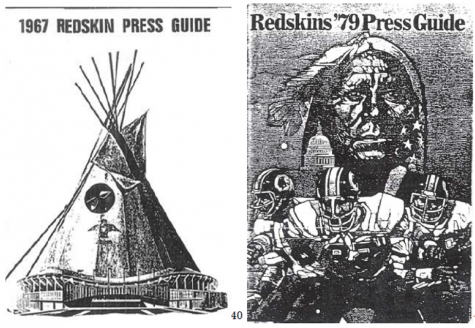

Some highlights from the official 177 page opinion document include…

Multiple dictionary definitions.

And many more.

Far from tyrannical (as some in the #tcot echo chamber on Twitter have suggested today), this decision is well within the purview of the federal government, the guarantor of Intellectual Property. Protection of intellectual property, that is, in a manner that prevents individuals from using others’ proprietary ideas to make money, is not an inalienable right. The government has not banned Washington’s football franchise from calling themselves the “Redskins.” Instead, they have reevaluated the value of protecting such a trademark and determined that its harm (the marginalization of an entire race) exceeds its benefit (preventing individuals from profiting from ideas that are not their own).

It is unlikely that this decision alone will precipitate a name change. The team will, undoubtedly, appeal the decision and there is a chance an appeals court could once again rule in its favor. However, the movement to change the name is near critical mass. Now that the USPTO will no longer enforce the “Redskins” trademark individuals are free to create their own Redskins merchandise to sell for profit.

In fact, they have always been free to do so, but the Washington Redskins now have fewer tools at their disposal to go after trademark infringement. Which is not to say we condone or recommend such an action. Not only is still remarkably offensive, but Washington Redskins owner, Dan Snyder, has never been one to shy away from a lawsuit.

Unfortunately, loss of revenue from unofficial merchandise sales are probably of little concern to an organization worth a reported $1.7 billion. Yet the USPTO decision is one of great symbolic importance and illustrates an ongoing trend: if public opinion continues to move against using an obvious racial slur as a mascot, Washington owner, Dan Snyder, may need to reconsider the declaration he made in May 2013:

“We’ll never change the name…It’s that simple. NEVER — you can use caps.”