In addition to the much more contemporary mass slaughter of ethnic Chechens by the Russian Federation (and earlier waves of deadly internal deportations by the Soviet Union), there’s the simple, horrifying reality that the Sochi Olympics are being held pretty much at ground zero of a 19th century genocide/mass expulsion.

In addition to the much more contemporary mass slaughter of ethnic Chechens by the Russian Federation (and earlier waves of deadly internal deportations by the Soviet Union), there’s the simple, horrifying reality that the Sochi Olympics are being held pretty much at ground zero of a 19th century genocide/mass expulsion.

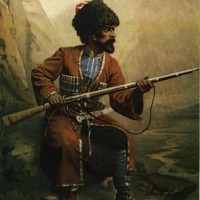

In May 1864 — 150 years ago this coming May — Imperial Russian troops completed the conquest of the independent multi-ethnic country of Circassia, located in an area stretching from the Black Sea into the Caucasus Mountains that includes or borders on the still-troubled Abkhazia and Ossetia regions. These Russian troops killed or starved 600,000 Circassians of various ethnicities (who were predominantly Muslim at that point) during the Circassians’ last stand that year, after several years of Russian invasions. The final battle occurred not far from Sochi. The Imperial Russian Army then mass-marched 900,000 more people out of their villages and expelled them in wave after wave of ships leaving from Sochi’s port and other nearby coastal towns to cross the Black Sea.

Sochi had been the cultural and political capital of Circassia and the Circassians (a term which refers collectively to the country’s citizens of all ethnicities, including perhaps most prominently the Adyghe people) before the Russian Empire pushed southward to claim the country. 1.5 million Circassian citizens were killed in the region or deported to Ottoman Empire. No more than about 25% of the country’s entire non-Russian population remained behind in their traditional homeland (and most of those survivors were forcibly relocated internally eventually).

One place they were permitted to settle within the Ottoman Empire, beyond what is now Turkey, was in the East Bank, in what’s now the Kingdom of Jordan. They became an important group in a small community that would later become the capital when the country gained independence, and they now represent a full 1% of the citizens of Jordan. Opposition to the Sochi Olympics and the upcoming key anniversary has been a motivating force in reinvigorating activism among Jordan’s Circassian population.

Today there are at least 3 million Circassians living outside Russia — and another 700,000 still in Russia today, including fewer than 125,000 members of the Adyghe ethnic group.

Russia has ignored the diaspora’s demands for recognition, let alone right of return. There has certainly been little mention, whether by Russia or the U.S. media, of the region’s history from before the Imperial Russian period, including the fact that it was the capital of a once-free nation with a rich cultural heritage.

Then again, maybe Russia’s brutal conquests in 1864 are an uncomfortable reminder that the United States military was busy committing the exact same acts of violence in the 1860s and 1870s against American Indian nations making their last stands against the U.S. Cavalry in the American West.