Like many U.S. communities large or small, there’s a debate afoot in Newton, MA about the merits of “development” and “growth,” as has occurred every decade without fail, probably since the earliest second ship landed in an American community after a first ship already had.

Below is an excerpt from one of a number of rather frustrating recent local commentaries against urbanization and densification of Newton, Massachusetts. I wanted to link to the long one published this week, but it wasn’t online yet — and this one will do for my purposes, as the specific people involved are less relevant to my analysis than the sentiments expressed:

Newton is the home we cherish. We value its character, history and scale. Newton residents are deeply invested in their community, both economically and emotionally. Whether they have been living here for decades or recently moved here, most residents chose Newton precisely for its suburban qualities, not because they hope to see it grow ever more urban.

[…]

All discussion of “smart growth,” “transit-oriented development,” and “right-sizing” is misdirected because Newton is already “right-sized.” Newton is not yet overcrowded, but risks becoming so.

[…]

In truth, Newton is a suburb, not a city, so imbued with the character of its 13 villages that it has little in common with a typical urban environment. Newton has benefited from transit-oriented development for more than a century, as businessmen who worked in Boston found that the railroad and later the trolley could bring them to work in Boston each morning in half an hour, then home again in the evening, allowing them to live with their families in an environment of clean air, tree-shaded streets and yards, and wide lawns. Remarkably, all these years later, we still enjoy the same advantages. And most residents would probably agree that neither biking, jogging, or walking is improved by denser development.

It takes a certain amount of self-absorption and myopia to genuinely believe that these suburban locales (which, I can verify after knocking on doors for campaigns in several states, all basically look identical) are somehow unique snowflakes, with incomparable community values, visual aesthetic, and appeal to home buyers. It takes an additional dash of naivete to genuinely believe that a community one is about to move into will remain unchanged forever.

A certain attitude

The attitude captured above — generally coming from any place’s “longtime residents,” who in Newton’s case lord that status over everyone despite almost universally having moved into the area half a century or more after my own family — is fairly typical of most communities like this. It boils down to “develop this far, and no further.”

It’s a view that says it was ok that everything changed hugely right up until my arrival, after which it must freeze in place and never, ever change again, even as the population grows and societies become more complex. It’s pulling the ladder up behind one’s self and slamming the door shut. I don’t think it’s as much NIMBYism as a reactionary fear of the unknown and fear of change. It’s gatekeeping via arbitrary construction limits to prevent new residences, thus obviating the need to become an actual gated community.

Sometimes I want to tell suburbanites complaining about “urbanization” and “pro-density” policies that the existence of their houses in the once-undivided miles of fields behind the house I grew up in is affecting my hay production for the local horse-drawn carriage industry. And the ice man is having trouble keeping up with the growing population’s ice box needs.

Yes, we should all go back to a time when there were just vast sprawling tracts of farmland behind my family’s house (I’m the fifth-generation in it, not that it matters), because all the development that happened afterward was just too crowded and there was too much construction.

According to my literal back yard and its history, we should have frozen in time before 1900 and never built anything since. But even that’s not fair to the people whose houses were built in the 1880s or 1870s and had to see the newcomer house I live in get put up. The railroad generation never expected streetcars to be added all over the community! The stagecoach generation never wanted the trains! Oh the horror. Let’s just roll it all back to pre-colonial status and call the whole thing off.

Tempus fugit

It would be valid to critique the type of development, or the process of development, even the impacts (which are real). But change itself? Time marches onward. Each generation conceptualizes (and remembers) the city differently from the last. And that’s not good or bad, it just is.

But it means development will continue too. We need to make sure it’s sustainable, responsible, and conceived within a bigger picture plan. The debate should not be Yes to Development or No to Development — that’s unrealistic and pointless — and it shouldn’t be Yes or No to one specific project — that’s tunnel vision. The debate should be about what kind of development is most desirable, what kind is needed, and how to make it all fit together harmoniously.

What kind of a community are we hoping to have in twenty years or more, for example? What kind of businesses and industries do we hope to attract? What level of services do we want to provide publicly? What kind of schools do we want? Do we want to be a multi-generational community or focus on fostering population weighted toward a specific age range? How do we best achieve all those goals?

Public participation is an important part of that conceptualization process. But it’s important in the sense of shaping the direction and preferences of a broader, longer-term vision for development on a citywide basis. It’s not helpful or useful for one activist faction to try to veto all development of any kind. That always fails in the long run, and it then results in undesirable policies being rammed through without public input either way, which is the worst possible outcome.

Envisioning the future

Citizens should be engaging in conversations with each other and their officials about what they want their communities to become, not trying to freeze everything in place like Sleeping Beauty behind the magical hedges. Any growing community near any big population center will change into something over time that it isn’t right now, whether for good or ill. There’s just no way, realistically, to prevent change of all kinds.

We don’t get to decide whether our communities will become something else in the future — only what they will become.

For my part, I’d much rather have an increasingly efficient concentration of resources and services resulting from higher density living. And I’m a heck of a lot more interested in “urbanization” than the ecologically devastating and socially inefficient exurban monstrosities flowering across the country’s rural landscapes. But that’s still just my preference for a vision. Other people are welcome to their ideas of what would they hope the city will become in twenty years or more. I’d like to hear those ideas. I’m just not as eager to hear what they believe it was twenty years ago.

Since “all politics is local,” I’ll close with my all-time favorite quotation from Ta-Nehisi Coates:

“In the world of politics, nostalgia is a kind of quitting. It says, ‘I can’t deal with today, can we go back to yesterday?’ But a particular yesterday, without its attendant problems.”

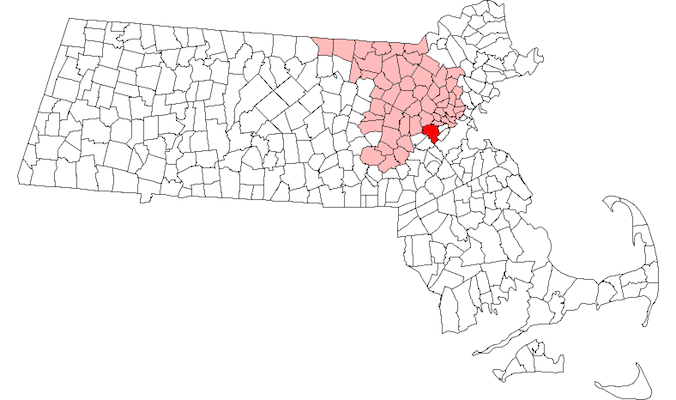

Newton highlighted within Middlesex County, Massachusetts. Credit: Justin H. Petrosek – Wikipedia)