Arsenal Essay: This isn’t Neville Chamberlain in 1938. It’s the world NOT taking the bait of Serbian gunmen in 1914.

The Crimea annexation has raised a crucial question: What is the world to do when a country with a large military and nuclear weapons decides to end a (voluntary, it turns out) period of non-aggression toward its neighbors?

The Crimea annexation has raised a crucial question: What is the world to do when a country with a large military and nuclear weapons decides to end a (voluntary, it turns out) period of non-aggression toward its neighbors?

For a while, the Soviet Union and Russia was so bogged down by the 1980s Afghanistan debacle and economic problems of the 1990s that it wasn’t in a strong position to intervene militarily in its European neighbors’ political affairs as it had once regularly done.

But by the mid-2000s, Russia’s military was back up and ready. The United States and the wider Western world appears to have mistakenly convinced itself that Russian non-intervention in Eastern Europe was due to universalizing of norms against such interference and some sort of implicit global check against it.

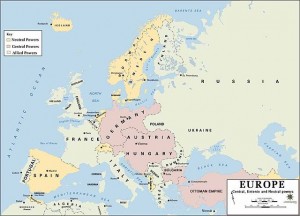

Putin doesn’t appear to feel bound by any of those norms, after all (though the United States has had an extremely iffy track record on that as well since 1999). For some time now I’ve been firmly in the camp that this has more to do with restoring the pre-1914 Russian Empire and little to do with restoring the USSR. I think Putin’s vision of Russia is a lot like the Russia that was a European power with an inferiority complex and a Peter the Great-inspired desperation for Europe’s respect but not its approval.

It also calls to mind the arrogant Russia that saw itself as the older brother (and divinely chosen leader) of all Slavs everywhere, whether they liked it or not — and the White Man’s Burden Leader of the near abroad (especially Central Asia, as we’ve seen flashes of again recently). We’ve seen the revived patronizing attitude of Russians who simply can’t comprehend why Ukraine wouldn’t want to be part of Russia again.

Of course — as I’ll return to later in this essay — that was the same “Older Brother Russia” with the largest land army in the world that invaded the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in response to an Austrian police action in Serbia following the Serbian assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914 (and Serbia’s alleged refusal to hand over the terrorists).

Rather than the Slavic World-Tsar liberating the Yugo-Slavs (the Slavs of the South), it brought the world into a devastating war that collapsed four empires, including Russia’s.

But let us return to Putin’s neo-imperial Russia of today. The lack of Russian invasions in Eastern Europe in the past nine years — apart from the disputed circumstances of Georgia in 2008 — seems now to have been more out of the “goodness” of Putin’s heart than out of any real commitment to respecting the independence of the Federation’s neighbors.

Putin’s revelation is that the 1956 rules still apply no less than they did in 1956, when the Soviet Union violently invaded Hungary (an anti-NATO Warsaw Pact member) to preserve communist rule there, and NATO was forced to watch passively because it could not risk a nuclear war over the matter.

Does the current Russian leadership, like the Soviet leadership of 1956, have enough sense to realize that it can only get away with interventions in its “sphere of influence” or will he press his luck? At the end of the day, it’s at least partly a matter of voluntary forbearance, as to how far Russia pushes. But partly as the hawks are telling us, it’s also about whether NATO and the United States are a credible umbrella for NATO members in Eastern Europe. As in: Is NATO really prepared to honor its defense obligations to the Baltic Republics if Russia intervenes there too?

I don’t know for sure if we’d actually launch a war if Russia invaded Estonia, say, but I do know that the United States isn’t twiddling its thumbs either — and is working to make sure that doesn’t happen in the first place, so that we never have to find out. Contrary to Republican belief, President Obama has been taking strong measures to shore up NATO allies in Eastern Europe against Russian aggression. Here’s the New York Times on the moves:

Since President Vladimir V. Putin ordered troops to seize Crimea, Mr. Obama has become increasingly engaged, blitzing foreign leaders with telephone calls, imposing sanctions and speaking out more frequently.

To reassure nervous allies, he sent six extra F-15C Eagles to Lithuania and 12 F-16 fighter jets to Poland. Mr. Obama, who met here with Anders Fogh Rasmussen, the NATO secretary general, will further bolster defenses in Eastern Europe by rotating more ground and naval forces for exercises and training in Poland and the Baltic countries; update contingency planning; and increase the capacity of a NATO quick-response force.

“Putin just declared war on the European order and it’s demanding that the United States focus on Europe again as a security issue,” said Damon Wilson, a former national security aide to Mr. Bush and now executive vice president of the Atlantic Council. While some Republicans have pushed the president to be tougher, Mr. Wilson praised Mr. Obama’s response. “I don’t think I’ve seen the president more personally engaged on any foreign policy crisis in a concerted way as he has been on Ukraine.”

This might not do much to help or re-assure non-NATO members such as Ukraine, Moldova, or Sweden, but we haven’t ever legally bound ourselves to defend them in the event of a foreign attack. The administration is striking a balance by re-affirming our existing commitments and alliances without drawing us into fresh entanglements that risk a World War I-style avoidable meltdown into war between major powers.

Would the world of 2014 have avenged the archduke?

In 1914, Austria tried to invade Serbia because some Serbians had assassinated the Archduke. This prompted a Russian intervention. Which prompted a German attack on Russia and Russia’s ally France. This attack veered through Belgium, prompting a British intervention.

At any point in that chain of events from the assassination onward, each major power could have realized it was stupidly self-destructive and mutually destructive to get involved or execute its initial plan.

Austria itself could have shown reasonable forbearance, especially given the repeated Serbian government’s offers of cooperation on the investigation. This would have been a more enlightened path than invading Serbia over a refusal to hand over terrorists within its borders, but it was 1914, and the United States blundered into the same scenario as recently as 2001 in Afghanistan… so it’s an easier mistake to make than one might think.

Even so, the others could still have stayed out. Russia could have not intervened to aid a loosely aligned ally in response to Austria’s over-reaction. Germany could have stayed out and not egged on Austria’s invasion plans. Or Germany could have not attacked the largely uninvolved France and waited for the Third Republic’s shoddy alliance with Imperial Russia to disintegrate under their own indifference and instinct for self-preservation. Britain could have ignored German maneuvers through Belgium instead of launching a land invasion it couldn’t finish.

There were any number of courses that could have prevented war, had the European powers chosen to do something other than what they did. Indeed, between the Archduke’s assassination and the actual start of hostility a month elapsed, and Britain was working frantically (in vain) to persuade the European powers to meet for a peace conference to solve the matter without war, but they weren’t too interested and were over-confident in their ability to prevail by force.

Knowing when not to respond

The fact is, sometimes, part of being a major power or even a superpower is knowing when to ignore blatant provocations, or at least respond to them constructively and non-violently. True, the United States has often used far smaller pretexts than Russia’s invasion of Crimea to justify massive wars. On several occasions (the Mexican, Spanish, Vietnam, Iraq Wars) the pretexts are now widely believed to have been literally made up entirely. We also have made a habit for two decades of repeatedly poking Russia and interfering in its old “buffer zone,” which was an irresponsible ongoing provocation.

But we have also sometimes held back, even when outright attacks were made against the United States or our military personnel.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, for example, the United States intentionally refused to respond to the unintended but fatal downing of U.S. surveillance planes by Soviets in Cuba while photographing Soviet missile site construction, because the cost of responding would have been instant global nuclear war. Here’s an account by then U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (who later went on to drag us deep into Vietnam, of course):

before we sent the U-2 out, we agreed that if it was shot down we wouldn’t meet, we’d simply attack. It was shot down. … Fortunately, we changed our mind, we thought “Well, it might have been an accident, we won’t attack.” Later we learned that Khrushchev had reasoned just as we did: we send over the U-2, if it was shot down, he reasoned we would believe it was an intentional escalation.

The attack proved to have been a mistake against explicit orders from the Soviet high command. Taking the high road saved the world. Nevertheless, the U.S. wasn’t doing nothing. President Kennedy was taking the necessary precautions militarily and diplomatically to ensure the country was prepared to respond to the larger Soviet provocation in Cuba. Knowing when to hold back on returning fire and weighing the scale of provocations relative to the danger of responding is a key part of responsible leadership when you hold the power to destroy the world and yourself.

The annexation of Crimea is an opportunistic Russian overreaction to events in mainland Ukraine. It is fairly similar to Austria’s opportunistic overreaction to the Archduke’s assassination, which gave them a plausible (if foolish) reason to go to war with a longtime thorn in their Balkan side. But the rest of the world didn’t need to go along with it and be led into war. Had all of Austria’s allies instead said — much as Italy did right before switching sides as war broke out — “forget our alliance, this is ridiculous and I’m not going to be a part of this nonsense,” Austria would have found itself isolated and ostracized rather than the trigger mechanism for a world war.

The United States, under President Obama, is following a wise course:

- Acknowledge that the Crimean annexation is unacceptable but not intolerable. A subtle distinction, but a real one.

- The loss of Crimea, while terrible, is not worth going to war, particularly as we have no prior agreement to defend Ukraine. So, Crimea is Ukraine’s responsibility.

- There are non-military ways to punish Russia for this — via sanctions, isolation, etc.

- Provide more military aid to existing NATO allies to help raise the upfront cost and non-feasibility of an initial Russian invasion (Ukraine was a pushover target with a disrupted chain-of-command due to the concurrent Revolution, Poland won’t be).

This strategy sends a signal that no, it’s not ok to invade your neighbors just because you can and have nukes, but we also understand that you seized a narrow window of opportunity to attack a virtually defenseless country and now we’re going to make sure you can’t go farther.

This approach could be termed “No Crying Over Spilled Milk, But Let’s Not Spill More.”

With almost any other country we would be following a very different playbook: the one we used in 1991 after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990. It was a blatant aggression and attempt to seize a nearby “former province,” but Iraq didn’t have nukes or any friends on the UN Security Council. (Kuwait also had oil we wanted, to be fair.)

But that’s the thing: A realistic foreign policy isn’t always consistent, by necessity. It’s a balancing act of applying a consistent vision where possible and accepting where it is not possible.

President Obama lives in a realistic world. His policy strikes a balance between acknowledging the limitations of U.S. power (and the extent of Russia’s power in the situation) and the need to avoid signaling that it’s open season on Europe.

And really, isn’t that the original point of NATO? To deter a Russian (Soviet) invasion of the European continent? Or more specifically: to protect those countries outside the Eastern Bloc and only those who had been accepted into NATO. The intent was never to stop Russia from invading every one of its neighbors, because that wouldn’t have been realistic. We have no more ability to stop Russia from taking Crimea today than we had to keep the Soviets from invading Afghanistan in 1979.

We can bolster our allies and deter foreign aggression against them, but we can’t guard the entire world against an aggressive nuclear-armed major military power. To think otherwise is to invite both magical thinking and a return to a continental war in Europe. But, unlike in 1914, we still have to keep the nukes in mind, just like we did in 1956, 1968, and all through the Cold War, whenever the Soviets rolled into a neighbor already under its sway.

One can only use force to counter the excessive avenging of the archduke in a world where it’s not immediately obvious that a military response will bring ruin on everyone. It did anyway in World War I, but we didn’t realize it at the time. Let’s realize it this time.

And: Let’s stop lecturing Russia so self-righteously about violations of international law when just over six months ago we were about to bomb Syria without U.N. approval. “Standing for something,” as Obama’s critics on Crimea want to see us do, begins at home.