Here’s a global warming impact you may not have considered: saltwater contamination of drinking water in some coastal areas. It’s especially worth discussing, to me at least, because of my longstanding interest in water policy and because I just completed an environmental geology course, where we discussed the science behind drinking water supplies and coastal processes.

Basically, due to rising sea levels brought on by global warming, millions of Americans (and presumably people around the world) face possible destruction of reliable water supplies in low-lying areas. This can happen due to saltwater intrusion into the groundwater — something that has been occurring on Long Island for some time now as wells deplete the aquifers — or by saltwater further penetrating coastal marshes in estuaries, reaching into the non-tidal freshwater marshes. Also individual incidents such as storm surges, which often contaminate drinking supplies and treatment facilities, are going to be exacerbated by higher sea levels.

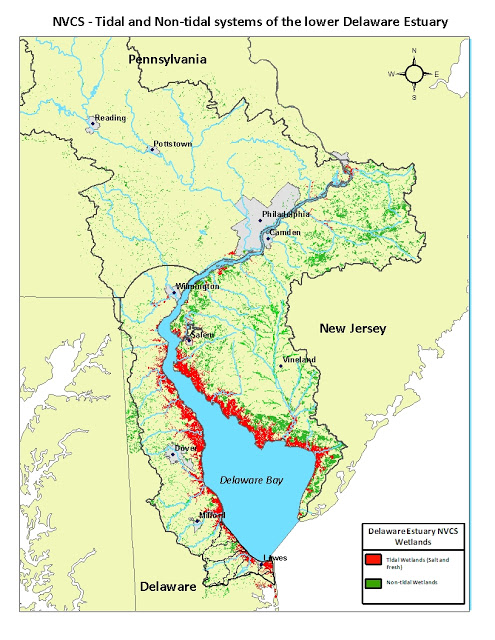

I’m particularly concerned because the state where I currently live (Delaware) has a coastline that is mainly an estuary, which was the subject of a new study on the impending problem. The potentially affected freshwater found in the coastal regions along the lower Delaware River and estuary provides drinking water for several million people in Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. I caution you that the blog post I’m about to quote has some glaring errors, but I’ve tried to fix/remove them here:

Fresh water that now is flowing to the sea in the Delaware estuary is threatened by future sea-level rise resulting from rising temperatures caused by greenhouse gas emissions, a new study finds. As sea levels rise, salt water will move inland up the estuary.

[…]

The Partnership for the Delaware Estuary studied impacts [PDF] on drinking water, tidal wetlands and shellfish like the local oysters and freshwater mussels in “Climate Change and the Delaware Estuary” and how people can adapt to help protect the threatened resources.

Drinking water, tidal wetlands and shellfish are key resources for the estuary; and all three are vulnerable to effects of climate change, including warmer temperatures, higher sea levels and saltier water. Oysters alone brought about $19.2 million into the [region] in 2009.

[…]

Currently a “narrow fringe of freshwater wetlands” protects the freshwater, but the wetland marsh plants are very susceptible to rising salinity.

It looks like there’s a pretty noticeable correlation between some of those freshwater wetlands and the population distribution on the New Jersey side…

If they become tidal wetlands instead of freshwater, that’s a big problem.

If you’re at all familiar with the disaster-ridden English colony at Jamestown, Virginia, then you probably know that, “the colonists soon discovered that the swampy and isolated site was plagued by mosquitoes and tidal river water unsuitable for drinking, and offered limited opportunities for hunting and little space for farming.” While the hunting and farming issue is not as much of a problem for the coastal United States these days, rising sea levels could basically expand a lot of estuaries and make much more of the seaboard’s water “unsuitable for drinking.” I know Jamestown had more problems than its drinking water, but everybody needs clean, freshwater to survive, and there are a lot more of us now living in threatened areas than ever before. We don’t want to repeat Jamestown if possible.

This post originally appeared on Starboard Broadside.