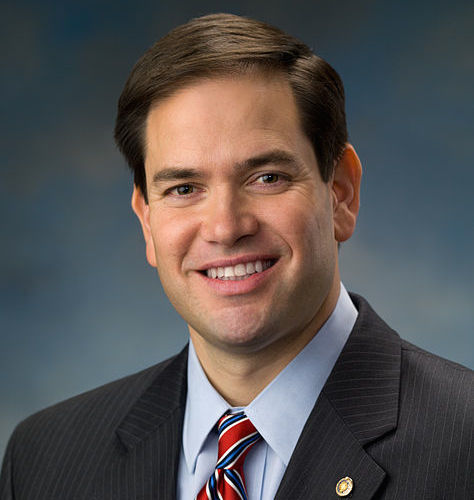

Don’t feel bad, Former Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell. We found someone probably as corrupt as you to run for president while you’re in prison — Sen. Marco Rubio of Miami, Florida:

As Mr. Rubio has ascended in the ranks of Republican politics, Mr. Braman has emerged as a remarkable and unique patron. He has bankrolled Mr. Rubio’s campaigns. He has financed Mr. Rubio’s legislative agenda. And, at the same time, he has subsidized Mr. Rubio’s personal finances, as the rising politician and his wife grappled with heavy debt and big swings in their income.

[…]

A detailed review of their relationship shows that Mr. Braman, 82, has left few corners of Mr. Rubio’s world untouched. He hired Mr. Rubio, then a Senate candidate, as a lawyer; employed his wife to advise the Braman family’s philanthropic foundation; helped cover the cost of Mr. Rubio’s salary as an instructor at a Miami college; and gave Mr. Rubio access to his private plane.

The money has flowed both ways. Mr. Rubio has steered taxpayer funds to Mr. Braman’s favored causes, successfully pushing for an $80 million state grant to finance a genomics center at a private university and securing $5 million for cancer research at a Miami institute for which Mr. Braman is a major donor.

Rubio seems pretty convinced that this is all above-board because he doesn’t try to hide any of his extensive campaign finance ties and personal (financial) relationships to Braman. I guess that’s the John Roberts school of non-corruption: If it’s fully transparent and there’s no explicit quid pro quo of money for favors/contracts, then it must not be corrupt.

However, it’s not even clear that there isn’t some kind of quid pro quo, formal or otherwise. It’s not pay-to-play, but Rubio certainly seems willing and eager to play as a thank you for all the paying.

“What is the conflict?” [Rubio] asked. “I don’t ever recall Norman Braman ever asking for anything for himself.” He acknowledged that Mr. Braman had approached him about state aid for projects, such as funding for cancer research, but said that he had supported the proposals on their merits.

[…]

Mr. Braman acknowledged seeking the occasional “small favor” from Mr. Rubio’s Senate office. There was the daughter of the woman who does his nails, Mr. Braman recalled, who had an immigration problem, and the student from Tampa who wanted a shot at military school. In both cases, he said, Mr. Rubio’s staff was quick to respond. (Mr. Rubio’s staff said it had decided not to recommend the Tampa student.)

Um, ok. Whatever this is, maybe it’s not strictly speaking illegal, but it’s certainly against the spirit of ethics and anti-corruption laws and principles. It’s disproportionate and narrow favoritism for a specific wealthy benefactor.

And I guess Rubio would probably suggest he’s not the only one doing this kind of thing and just happens to be one of the least affluent and most indebted high-profile U.S. politicians (and certainly is one of the least cash-flush presidential candidates on a personal basis).

There’s a lot more in the NY Times article (quoted above) about how much Rubio has benefited from Braman’s support. The latter has been saying he was going to make Rubio president since before he was even in the U.S. Senate — and he’s paid for most of the steps to get him close to that goal.

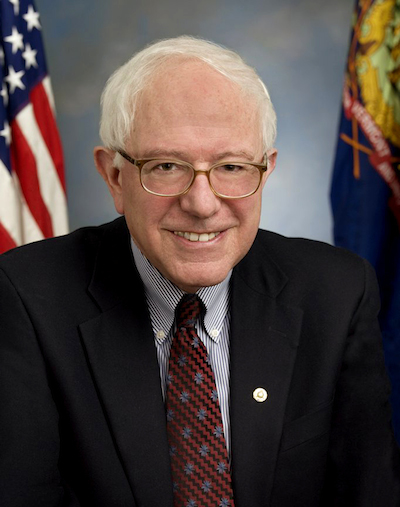

Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) announced his Democratic presidential campaign this week and raised an impressive $1.5 million in the first 24 hours from about 35,000 donors. Although Clinton obviously has a much larger warchest on tap, this figure has at least put him solidly on par with major Republican contenders

Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) announced his Democratic presidential campaign this week and raised an impressive $1.5 million in the first 24 hours from about 35,000 donors. Although Clinton obviously has a much larger warchest on tap, this figure has at least put him solidly on par with major Republican contenders