The Jordanian government was not messing around with its “Earth-Shattering” Response line to the execution of their pilot by ISIS. In addition to rejoining the reduced Syria coalition, huge air formations of Jordanian fighter-bombers will target ISIS positions inside Iraq, according to the Wall Street Journal:

The Royal Jordanian Air Force in recent days has begun rehearsals for a large-scale attack on Islamic State forces. But the initial wave of reprisal strikes, which will include Jordanian and U.S. warplanes, is being focused on targets in Syria, coalition officials said. Any strikes in Iraq would come later.

[…]

Jordan’s airstrikes have typically involved small formations of planes, while the reprisal for the killing of the pilot will involve as many as two dozen warplanes, officials said. In recent days, the U.S. has helped develop potential targets in Syria for Jordanian warplanes, coalition officials said.

Expanding into Iraq would allow the Jordanians to strike at more targets, coalition officials said. Iraqi officials weren’t available to comment, but the Shiite-led government so far has balked at allowing Sunni Arab nations such as Jordan to conduct operations.

It should be noted that a Jordanian air campaign in Iraq would probably be highly illegal under the current arrangement, because the government of Iraq explicitly opposes any Arab state bombing targets in Iraq (while it has invited Iran, US, Australia, Canada, and Europe to do so).

Of course, past Jordanian operations in Syria are also essentially illegal, since the government of Syria opposes non-cooperative air raids on its territory, even in reaction to attacks against Iraq (or Jordanians) staged on or from that Syrian territory. But there will probably be a good deal more controversy if Iraq rejects Jordanian bombing in Iraqi territory and then Jordan does it anyway.

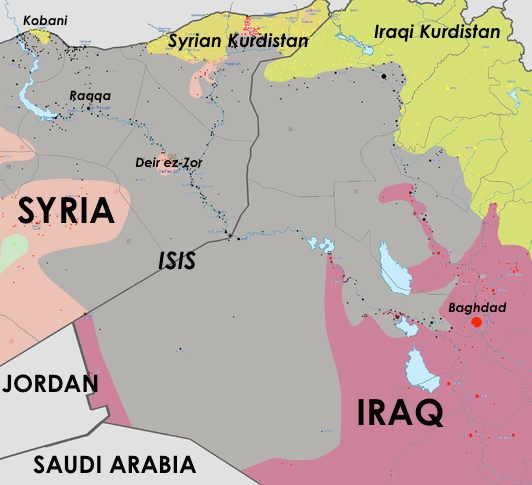

Map of estimated ISIS control in western Iraq and eastern Syria on February 3, 2015, relative to Jordan and Saudi Arabia borders. Adapted by ArsenalForDemocracy.com from Wikimedia.

Or, I suppose, authoritarian

Or, I suppose, authoritarian