Note added January 11, 2015: We are hoping to have a review of the game available on this website soon from one of our correspondents. Unfortunately, he has reported that there’s a bug that stops the game about a third of the way through. You might want to wait for it to be patched before buying the game.

NPR recently reported on a very cool video game that brings to life a traditional Iñupiat adventure story from Alaska. It’s called “Never Alone” and is produced by “Upper One Games,” a studio founded in 2013 by Cook Inlet Tribal Council of Alaska to help promote the native cultural heritage to a new generation of its members and to the wider world.

The game, which brought on board a number of respected veterans from the video game industry, was developed with extensive input — on plot, in-game art, and structure — from those who know the story best:

“We didn’t want this to be an outsider’s view of what the Inupiaq culture was. We wanted it to come from the people themselves.”

Never Alone is based on a traditional story known as Kanuk Sayuka and the experiences of Alaska elders, storytellers and youth. The story follows a young Inupiaq girl and an Arctic fox as they go on an adventure to save her village from a blizzard that never ends.

Game developer Sean Vesce has 20 years of experience in the industry working on action titles like Tomb Raider. He recently went to Barrow, in far northern Alaska, to watch the students play a demo of the game. He says that day was his most memorable experience from the project.

The puzzle platformer game will be released for Windows (via Steam), PS4, and Xbox One in November. Here’s the official trailer:

It looks like an incredible game, and it features a female lead playable character, as well as bringing both cultural diversity and an unusual structure (since it was built around the Iñupiat cultural/linguistic worldview and oral traditions, rather than around the industry-dominant Euro-U.S. cultural framework).

Here’s the gameplay description from the official website:

– Play as both Girl and Fox – switch between the two characters at any time. Girl and Fox must work together to overcome challenges and puzzles as each has unique skills and abilities. A second player can join at any time for local co-op play.

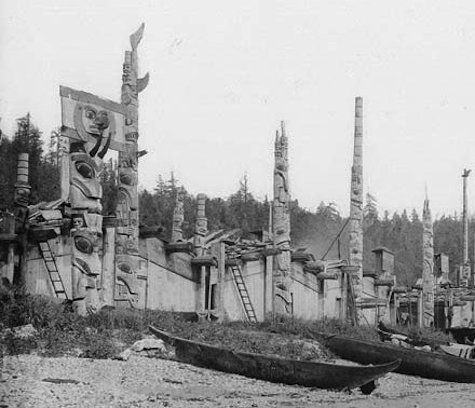

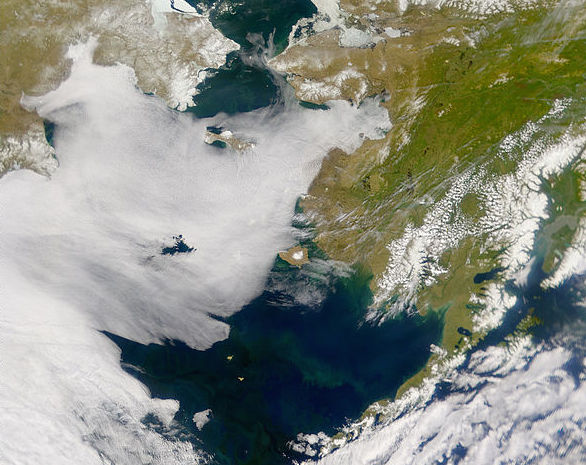

– Explore perilous Arctic environments, from tundra to coastal villages, from ice floes to a mysterious forest. Brace yourself against gale-force winds and blizzards; face treacherous mountains.

– Meet fascinating characters from Iñupiaq folklore – Manslayer, the Little People, Helping Spirits, Blizzard Man and more. Never Alone was crafted in partnership with Alaska Native elders and storytellers for true authenticity.

– Hear the story of Kunuuksaayuka as told by a master Iñupiat storyteller in the spoken Iñupiaq language — a first for a commercial video game.

– Unlock special video Insights recorded with the Iñupiaq community to share their wisdom, stories and perspective.

They also worked to appropriately balance the game play with the source material:

One famous Iñupiaq storyteller named Robert Nasruk Cleveland, born in the late 1800s, was renown for his storytelling skill. Many of the great examples of traditional Iñupiaq stories are closely associated with him, including the story of Kunuuksaayuka.

The Never Alone team located Robert Cleveland’s daughter, an Iñupiaq elder named Minnie Gray, to obtain permission to use the story as the inspiration and main narrative spine of the game. The team worked directly with Minnie to ensure that, as the story was adapted to the needs of a video game, it maintained the wisdom and teachings of the original.

Here’s another video on the impact they hope to have with “Never Alone”: