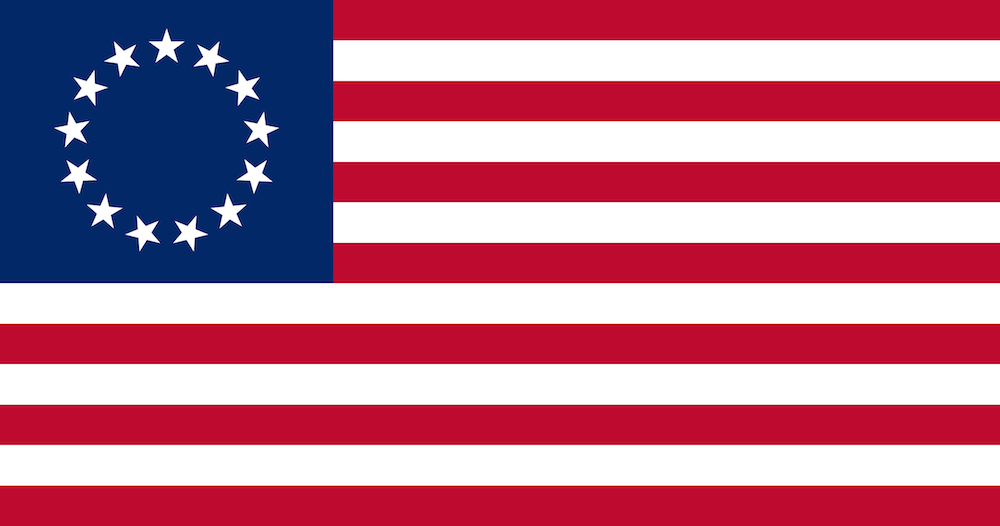

The real story of the origins of the U.S. political system. Composite oped from two new essays (here and here) in The Globalist.

You’ve read the story before. A number of loosely aligned, merchant-dominated offshore territories of a European empire begin chafing at their distant monarch and the high taxes he imposed without giving them a reasonable say in their own governance.

Predictably enough, their mounting dissatisfaction is met with an increasingly overbearing response — including military deployments. That strategy is pursued until the provinces reach a breaking point.

They declare themselves free of the faraway king and initiate a rebellion. Not all the territories are persuaded to join. Some prefer to remain loyal to the crown.

The rebellion binds together a small collection of sovereign entities into a union, equipped with a weak, loosely formalized provisional government. Its purpose is to direct the union’s foreign policy and manage the rebellion.

Government after monarchy

Having declared themselves without a king, the newly independent elite must devise a replacement system of government for the continued union.

For a time, they consider the possibility of bringing in another member of the European nobility to serve as king. Such an invitation or election of an outsider as king was common in Europe for centuries, from Poland to Sweden to the Holy Roman Empire. Even the papacy is an elective monarchy.

But eventually the merchant elites and past commanders of the rebellion decide they have been doing fine without a royal. They are now content to continue to strengthen the temporary system as it is.

The exceptional story takes shape

These elite gentlemen look around at other precedents for other self-governing states without kings. Smaller free states — such as Florence and Venice — had previously installed non-hereditary systems of rule by the commercial elites and major families. They had called them “republics,” after the elite-run classical “Roman Republic.”

Elections in such systems are highly indirect and susceptible to manipulation. They are also restricted to a very small number of participants. Essentially, the only voters are members of the propertied, male elite — usually white.

After all, they make no secret of the fact that this exclusionary voting franchise suits the new country’s leaders’ aims anyway. They are not interested in creating a democracy. Rather they are keen to establish a republic insulated from the passions of the mobs.

It is then agreed that under the new union of rebel provinces, each member republic would send delegations to the union’s government, but they will be answerable to their home governments. This further would keep the regular people away from any major levers of power.

Finally, they devise an elaborate system of checks and balances. The ostensible purpose is to preserve the sovereignty of the member republics within the union. The bigger purpose is to prevent the “tyranny” of a central government and an executive. The union will have weak powers of taxation — only enough to mount a common defense of the member republics.

This is, of course, the story of the Republic of the Seven United Provinces in Netherlands and their departure from Spain — about two centuries before the United States constitution was ratified by thirteen former British colonies.

So much for America’s origin story being exceptional, as claimed for so long.

The Dutch precedent was a model, both to be emulated and avoided, for the framers of the U.S. Constitution and those advocating for its adoption. Far from being an “exceptional” idea, the original version of the United States was just the latest iteration of an existing system. It is what came after that that made it exceptional.

Almost before the ink had dried on the U.S. Constitution, the United States and its citizenry — indeed, even its government officials — began adapting the document in other directions the framers had never intended or anticipated.

That is probably for the best, from the world’s perspective, and from the country’s, since rule by a narrow slave-owning elite is not exactly a paragon of excellent governance for the world to follow.

Read more