The following analysis was originally published at The Globalist.

After the recent callous murder of 30 British tourists in the holiday resort of Sousse in Tunisia and the earlier attack on the Bardo Museum in Tunis, some in the Tunisian security establishment are propelling a new narrative in friendly media (with assistance from willing critics in France and beyond).

According to this new chain of responsibility, it has become much harder in Tunisia to protect the country – and tourists – against the infiltration of terrorists from Libya (partially true — training for both attacks happened there), and that this makes whatever happens ultimately the UK’s fault (not true).

The implication is that the UK and other overly hasty, zealous and/or optimistic Western supporters of the 2011 intervention in Libya now share some responsibility for that country’s plentiful troubles — and by extension Tunisia’s security problems and the deaths of their own citizens.

This alternative explanation is perhaps offered out of frustration with Britain pulling back lucrative tourism relationships or eagerness to escape responsibility at home.

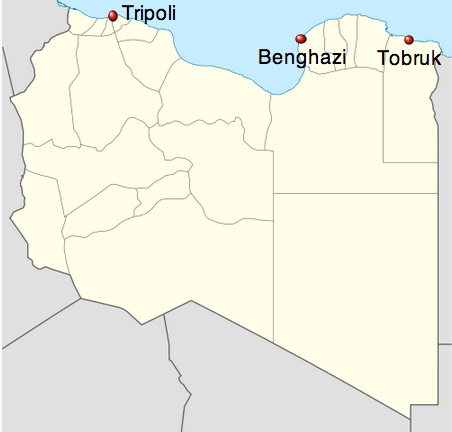

It sounds plausible, even gripping, at first glance. To be sure, Libya’s territory is now essentially lawless, with terrorists roaming freely and a three-way civil war. And Tunisia shares a long land border with Libya. Terrorists do indeed slip rather unimpeded across it into Tunisia.

But does that mean that countries such as the UK bear responsibility for the current struggles of neighboring Tunisia?

Remember cause and effect

That interpretation is not only a bit too convenient for Tunisia, but it also actually inverts some crucial timelines.

In terms of chronological cause-and-effect, some 1,000 Tunisian terrorists may be more responsible for Libyan instability than the other way around.

Certainly, Libya’s violent chaos does not make Tunisia more stable, but Tunisia is fundamentally grappling with a homegrown challenge. In essence, it is the echo effect of long decades of oppression under former ruler Ben-Ali that now leads to all sorts of contortions.

The Arab Spring originated in Tunisia in December 2010. Tunisia is also where the movement for change remains most intact – and where democratic power sharing has tentatively been mastered. However, life could not be changed overnight.

Mass unemployment, particularly among educated youth, remains a huge problem. The police, whose abuses sparked the initial uprising, remain an omnipresent antagonist. The state is flailing on how to guarantee free speech while stopping terrorist recruitment that capitalizes on these frustrations.

But such aggravations are not new and the recruitment is not new, nor is the Libyan war to blame.

Tunisia as a producer of terrorism in the region

Here is the upshot: A few Tunisian towns (PDF download) were contributing an astonishing number of jihadist fighters worldwide (in places like Iraq) before the Arab Spring occurred, let alone the NATO intervention in Libya – or the start of the jihad-magnet war in Syria for that matter.

After that, the floodgates opened and Tunisia reportedly became the absolute largest contributor of foreign fighters.

Thousands of these experienced Tunisian fighters – since 2010 some 3,000 are believed to have “served” in Syria and Iraq, more than from anywhere else – are merely starting to “rotate” back home now. Tunisia already had loose borders with Libya, which makes it easy to get back in.

There are also the would-be global jihadists who are turning inward on Tunisian targets because the government has succeeded in making it (somewhat) harder to reach foreign battlefields like Syria, which is still the primary goal location.

8,000 recruits were prevented from leaving in the first nine months of 2014. (Some are able to make it to Libya for training, but Libyan training of Tunisian terrorists dates to the 1980s. That is also not a new development.)

Tunisia’s recent terrorist attack that claimed so many British lives is one of the few recent incidents in the Middle East-North Africa region for which the UK bears little direct responsibility.

The internal politics of Tunisia – and even the factors for the rise of terrorist recruitment – remain substantially different from the other Arab Spring states. It would be a mistake to lump Tunisia’s challenges in with the rest. An honest assessment will go further toward solving them than misleading blame games.

General

General