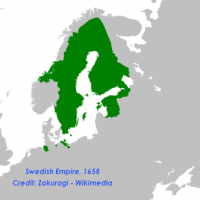

Though more recently known for its relative impartiality and determined neutrality (during World War II, they wedged themselves peacefully between occupied Denmark and Norway, and bitterly contested Finland), Sweden was once a powerful northern European empire dominating (or attacking) Norway, Finland, Denmark, the German states, Poland, the Baltic States, and Russia.

Though more recently known for its relative impartiality and determined neutrality (during World War II, they wedged themselves peacefully between occupied Denmark and Norway, and bitterly contested Finland), Sweden was once a powerful northern European empire dominating (or attacking) Norway, Finland, Denmark, the German states, Poland, the Baltic States, and Russia.

During the Thirty Years War of the 17th century, the Swedish Empire captured half the principalities of the Holy Roman Empire and sent colonists to the Mid-Atlantic in North America. Those days are long gone, and in Baltic Europe, Russia picked up a lot of the slack in the vacuum left by a receding Sweden in the 18th and 19th centuries.

In the post-World War II era, Sweden has maintained a relatively small military but tried to stay out of foreign entanglements, apart from some peacekeeping missions in Africa or international non-combat military roles, such as in Libya or Afghanistan.

Right about now, though, the Swedes seem to be wishing they were back to their old imperial glory days — or the next best thing: being a NATO member, something they previously have had no interest in. If Russia’s going back to the no-rules imperialism of yore, Sweden would like to be protected.

Non-aligned since the early 19th century, Sweden’s “splendid isolation” has endured two world wars and even the five-decade superpower slugfest that dominated the late 20th century. That could change, however, in the wake of Russia’s intervention in Ukraine. Last week, Swedish Finance Minister Anders Borg indicated that the defense budget, to which he had recently announced cuts, would be increased as a result of the crisis. Deputy Prime Minister Jan Björklund also publicly floated the idea of Swedish membership in NATO, warning that Russia could attempt to seize Gotland, a strategically located Swedish island province in the Baltic Sea, if it chose to attack the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Without international military help, Sweden’s military publicly believes it could hold out in an all-out conventional war for only one week. NATO membership brings a guarantee of international defense if attacked. So right now the old neutrality plan, translating to the go-it-alone approach, is looking pretty dicey.

Russia’s Gazprom conglomerate owns Nord Stream, an $11-billion pipeline running along the Swedish island that pumps 55 billion cubic meters of natural gas each year to Western Europe. Russian President Putin vowed to defend the strategically vital pipeline with the Russian Navy in 2006, and in one March 2013 incident reminiscent of the Cold War, two Russian heavy bombers and their fighter escorts skirted Swedish airspace and simulated a bombing run against the island. NATO’s Baltic air patrol responded. Sweden’s did not.

Russia was legally committed to uphold Ukraine’s neutrality and blew right through that stop sign. What’s to stop them from going after Gotland? International norms seem to be a voluntary thing for Russia these days.

Update: Following the September 2014 parliamentary elections, the incoming government (from the center-left) abandoned the previous government’s idea of having Sweden join NATO.

Description: Bill and Greg discuss discuss the

Description: Bill and Greg discuss discuss the

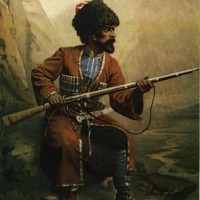

In addition to the much more contemporary mass slaughter of ethnic Chechens by the Russian Federation (and earlier waves of deadly internal deportations by the Soviet Union), there’s the simple, horrifying reality that the Sochi Olympics are being held pretty much at ground zero of a 19th century genocide/mass expulsion.

In addition to the much more contemporary mass slaughter of ethnic Chechens by the Russian Federation (and earlier waves of deadly internal deportations by the Soviet Union), there’s the simple, horrifying reality that the Sochi Olympics are being held pretty much at ground zero of a 19th century genocide/mass expulsion.