In 2001, during the opening weeks of the War in Afghanistan, the United States military — partly coming in alongside Taliban arch-rivals the “Northern Alliance” — got to experience firsthand the deeply complex and fluid border regions of (and surrounding) northern Afghanistan, which are far more vaguely defined in reality than on maps. The wider region remains home to a multitude of different ethnic groups, religions, languages, and cultures. Some of these populations are still semi-nomadic and many, at the very least, don’t constrain themselves reliably to the modern borders of the countries.

In 2001, during the opening weeks of the War in Afghanistan, the United States military — partly coming in alongside Taliban arch-rivals the “Northern Alliance” — got to experience firsthand the deeply complex and fluid border regions of (and surrounding) northern Afghanistan, which are far more vaguely defined in reality than on maps. The wider region remains home to a multitude of different ethnic groups, religions, languages, and cultures. Some of these populations are still semi-nomadic and many, at the very least, don’t constrain themselves reliably to the modern borders of the countries.

“East Turkestan”

One of the places (just barely) bordering northern Afghanistan is China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region. Xinjiang, sometimes formerly known as Chinese or East Turkestan, is China’s largest administrative area. It is located in northwest China, north of the Tibet region, and it shares borders with several former Soviet Republics, plus Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Xinjiang is nearly evenly split between China’s overall majority ethnic group the Han and the ethnic minority Uighurs (also spelled Uyghurs) — who are the largest ethnicity in the Xinjian region, a situation which is highly unusual for Chinese minority ethnic groups nationwide.

Uighurs argue (probably correctly) that they are an oppressed minority in China. The Communist Party, in return, doesn’t trust them, both because they are dissimilar from the rest of the country and because they actively waged an Islamic insurgency during the 1950s against the People’s Republic of China. This rebellion was nominally in support of their Nationalist allies, who had fled to Taiwan after the end of the Chinese Civil War at the end of the 1940s, but was of course largely motivated by a desire for self-rule after many generations of outside domination.

In fact, Uighur support for the Nationalists was a rare exception to their historic trend of generally resisting all outsiders, including a Soviet invasion in 1934, the Russian Empire in the 19th century, and various Chinese dynasties that attempted to assert control over the area throughout history.

They are, essentially, another of the many small and diverse warrior cultures of Central Asia, which we’ve seen in action in Afghanistan and Pakistan throughout the 1980s, 1990s, and the past decade — except that they happen to fall within China, on the map, as opposed to one of the “Stans.” And indeed they are more closely related to the ethnic groups in those areas than to the rest of China, which is one of the sources of conflict.

The population, as is true of much of the Western half of China (outside of Tibet), is heavily Muslim. As a result — and due to its borders with Pakistan and Afghanistan — they have been somewhat accidentally caught up in the Global War on Terror.

Wrong place, wrong time

During the confusion of the initial invasion of Afghanistan and efforts to catch those responsible for 9/11, the U.S. military rapidly detained a lot of people suspected of possible al Qaeda involvement and shipped them to the Guantanamo Bay military base in the U.S. exclave in Cuba.

Among them were 22 Chinese-born men who are ethnically Uighur and were living in exile in Afghanistan or the surrounding countries when U.S. special forces arrived in late 2001. Some of the Uighur detainees admitted involvement in the anti-Beijing “East Turkestan Islamic Movement” separatist group, which China considers to be a terrorist organization.

Beyond the specific detainees in Guantanamo Bay, some of the activists for Xinjiang’s independence are indeed associated with so-called “Islamic terrorism,” but this is arguably a new cosmetic face of a much longer resistance against Beijing. (As an aside, there’s a compelling case to be made that the same is true for the “Islamic terrorism” once again rocking the Caucasus region of Russia, in that Islam has become the latest face of a much longer resistance against a distant capital that favors a different ethnic group.)

It’s certainly true that some Uighurs have taken up arms once more against the Chinese government in the past couple decades, and many of those fighters have even gone to militant training camps in Afghanistan and Pakistan. But there’s still not much evidence that this is due to any desire for global jihad against the West, rather than due to convenience with so many nearby “experts” in the waging of modern insurgency.

Moreover, in terms of the detainees in Guantanamo, many were simply caught in the wrong place at the wrong time, while living as exiles outside China. None of those Uighurs who were taken to Guantanamo Bay in 2001, it seems, were associated with or particularly sympathetic toward al Qaeda.

Amazingly, this fact was determined by the government as early as 2003, a full decade ago. Yet, because the United States could not repatriate them to China due to their likely status as anti-governmental rebels, all the men were still in detention by 2008, when a judge finally ruled that the United States had to find new homes for them.

Suggestions of moving them to the United States — including to Newton, Massachusetts, where some of their defense lawyers lived (which seems to me like a pretty solid recommendation of their characters even after having been held for years without charge) — were universally met with unreasonable howls of terror by Americans.

Gradually, some of them were resettled in various countries around the world — usually through expensive deals with the U.S. government for various goodies, in part to offset diplomatic or economic retribution from China for agreeing to take in anti-Chinese rebels.

But it was not until the final day of 2013 that the United States finally released the last three Uighur detainees from Guantanamo Bay, to Slovakia, one of the six host countries. A full twenty of them were only released in the last eighteen months — again, despite having been cleared of involvement with al Qaeda back in 2003.

Rethinking Muslim insurgencies

China is no doubt still very upset that the United States didn’t just hand over “their” ethnic minorities for punishment, particularly after Uighur militants recently staged a suicide car-bomb attack in Beijing’s Forbidden City at one of the Communist Party’s biggest symbols in the country: the huge picture of Mao.

But perhaps China should consider a different strategy to end resistance in Xinjiang, much as the United States needs to change its approach to counterterrorism in Central and Southwest Asia. Addressing the root causes of discontent — often ultimately economic more than inherently identity-based — and returning autonomous or sovereign political control to various oppressed minority populations would go much further than endless military campaigns that cost many lives and a lot of money but never truly end resistance.

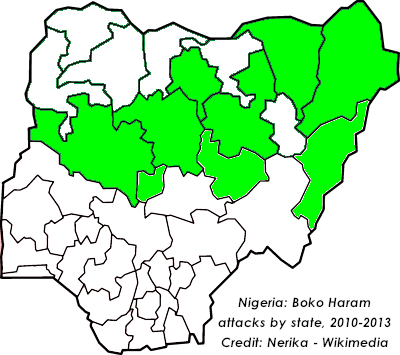

And the United States in particular needs to stop lumping together every rural Muslim male with a gun as an “Islamic terrorist.” It’s not a helpful approach to the conflicts from southeast Europe to northwest China and everywhere south of that (including much of Africa now). It’s just as bad as our refusal to make nuanced distinctions among different Communist-affiliated nationalist independence movements in Africa and Asia during the Cold War.

In fact, as we heard in 2004 from one detainee, we might be missing out on opportunities to make new friends:

One of the Uighurs held at Guantanamo went before a special tribunal on Friday to argue that he was not an unlawful enemy combatant and should not have been arrested in Afghanistan and kept in the detention camp here. The man, a 33-year-old with an artificial left leg, told the military panel that he was not an enemy of the United States and that he hoped America would one day help the Uighur independence movement.

We’ve heard this before, after World War II, when the United States decided to fight pro-American independence groups like the Viet Minh because of their Communist alignment, instead of embracing fellow anti-colonialists.

Unfortunately, as with recent terrorist attacks in Russia, the U.S. media is already beating the war drums to label the East Turkestan Islamic Movement in China and Central Asia a major threat to the United States, even though they have nothing to do with us and aren’t opposed to us.

Let us hope that the United States government will be chastened, at least briefly, by its grave mistake with the Uighurs we picked up in Afghanistan 12 years ago.

In 2001, during the opening weeks of the War in Afghanistan, the United States military — partly coming in alongside Taliban arch-rivals the “Northern Alliance” — got to experience firsthand the deeply complex and fluid border regions of (and surrounding) northern Afghanistan, which are far more vaguely defined in reality than on maps. The wider region remains home to a multitude of different ethnic groups, religions, languages, and cultures. Some of these populations are still semi-nomadic and many, at the very least, don’t constrain themselves reliably to the modern borders of the countries.

In 2001, during the opening weeks of the War in Afghanistan, the United States military — partly coming in alongside Taliban arch-rivals the “Northern Alliance” — got to experience firsthand the deeply complex and fluid border regions of (and surrounding) northern Afghanistan, which are far more vaguely defined in reality than on maps. The wider region remains home to a multitude of different ethnic groups, religions, languages, and cultures. Some of these populations are still semi-nomadic and many, at the very least, don’t constrain themselves reliably to the modern borders of the countries.  The huge New York Times investigation into the 9/11/12 Benghazi attack was

The huge New York Times investigation into the 9/11/12 Benghazi attack was  Another excellent article by Ta-Nehisi Coates (aren’t his always?):

Another excellent article by Ta-Nehisi Coates (aren’t his always?):