In an op-ed in the NY Times Sunday Review, Jeffrey Rosen discusses James Madison’s views on privacy and surveillance. In particular, Rosen argues that Madison made a slightly odd distinction between government invasions of privacy (which he wanted restricted) and the same from businesses or other people (which he didn’t really care about much). Then Rosen asks whether that distinction is valid or even still up to date.

In practice, the neo-Madisonian distinction between surveillance by the government and surveillance by Google makes little sense. It is true that, as Judge Pauley concluded, “People voluntarily surrender personal and seemingly private information to trans-national corporations which exploit that data for profit. Few think twice about it.”

But why? Why is it O.K. for AT&T to know about our political, religious and sexual associations, but not the government?

[…]

That distinction is unconvincing. Once data is collected by private parties, the government will inevitably demand access.

More fundamentally, continuously tracking my location, whether by the government or AT&T, is an affront to my dignity. When every step I take on- and off-line is recorded, so an algorithm can predict if I am a potential terrorist or a potential customer, I am being objectified and stereotyped, rather than treated as an individual, worthy of equal concern and respect.

Justice Louis Brandeis, the greatest defender of privacy in the 20th century, recognized this when he equated “the right to be let alone” with offenses against honor and dignity.

But he also lamented that American law, unlike European law, was not historically concerned with offenses against what the Romans called honor and what in more modern terms we call dignity. European laws constrain private companies from sharing and collecting personal data far more than American laws do, largely because of the legacy of Madisonian ideas of individual freedom, which focus on liberty rather than dignity.

What Americans may now need is a constitutional amendment to prohibit unreasonable searches and seizures of our persons and electronic effects, whether by the government or by private corporations like Google and AT&T.

Europe is way more aggressive about trying to curb private amassing of data. Meanwhile, both the U.S. government and private mega corporations — aided by the gushing of the American media — are pitching the concept of “big data” as a godsend and cure-all, thus necessitating mass collection and indefinite storage of data. Can’t throw all the data points in the data stew if you haven’t held on to all of them, the logic goes.

And it’s a fair question raised in this article. The phone company or the internet businesses knowing all our private information (and movements and habits) is allowed freely. Yet the government is supposed to be following various restrictions, due to the Bill of Rights — but why? Why don’t the protections extend to the private corporations? We’ve seen time and again that they willingly turn over all their data for “national security” and “public safety” reasons, sometimes without even being asked through a court order.

Our government need not construct a surveillance state unconstitutionally when corporate America will do it for them.

Addendum: On a partially related note, I highly recommend this article by Virginia Eubanks in The American Prospect: “Want to Predict the Future of Surveillance? Ask Poor Communities.”

Marginalized groups are often governments’ test subjects. Here are a few lessons we can learn from their experiences.

Almost a century after the start of World War I, Italy is

Almost a century after the start of World War I, Italy is

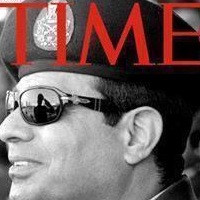

In the least convincing denial yet that he is building a cult of personality and permanent personal dictatorship, Egypt’s General Abdul-Fattah el-Sisi has

In the least convincing denial yet that he is building a cult of personality and permanent personal dictatorship, Egypt’s General Abdul-Fattah el-Sisi has