On the anniversary of Mike Brown’s death, another abusive police crackdown played out.

Last year, on August 9th, the death of Mike Brown at the hands of a police officer pushed the chronic abuse of an entire community at the hands of police to the forefront of global news media and kicked off a national movement.

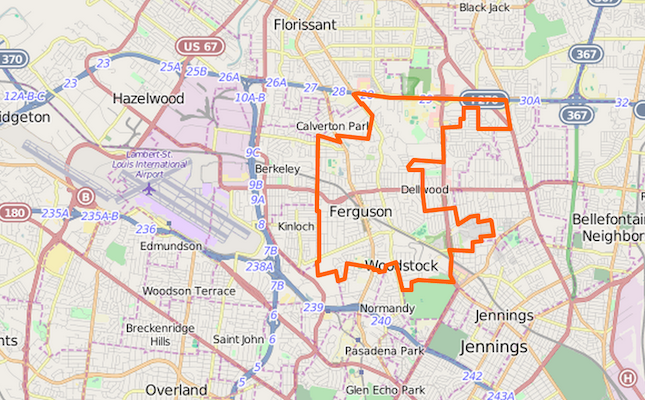

Ten days ago, on August 9th 2015, the first anniversary of his death, people began tweeting links to articles and feeds about violence breaking out in Ferguson. I naively thought that people were posting old articles, as a reminder of the trauma that Ferguson residents endured last year in the wake of Mike Brown’s death. It wasn’t until the next morning that I realized that the links being posted were brand new. It’s been a year to the day, yet St. Louis County Police Department still doesn’t seem to want to fix the problem.

Over the past year, Whiteness and its privileges have been under the microscope. More and more people of color, especially Black people, are able to document their interactions with Whiteness — from the smallest micro-aggressions to major instances of Police Brutality and abuse. Ferguson in the past week alone has shown examples almost all of these issues.

On the night of August 10th, a 19-year-old White girl decided she was going to show solidarity with St. Louis PD as the tension increased at the ongoing Ferguson anniversary protests. The girl is quoted saying that she was there to protect the police, because she would rather have something thrown at her, than to have something thrown at and possibly injure cops.

It seems strange that someone would feel that police with guns riot gear would need protection from peaceful protesters. Meanwhile, the same instinct isn’t felt for a 12 year old Black girl detained by St. Louis County PD in Ferguson during protests. When the news spread on Twitter of the girl’s arrest, the STL PD account was quick to respond that the girl had an ID that stated that she was 18 years old, despite the fact that there were eyewitness accounts of the girl stating that she was 12 when asking why exactly she was being detained. Apparently she posed the same threat that Dajerria Becton posed in McKinney, Texas: being young, Black, and female in front of the police.

Earlier that same day, prominent activists Netta Elzie and DeRay Mckesson were both arrested, along with many others, during a peaceful protest at the Ferguson courthouse. It wasn’t until the following day, upon release, that other detainees came forward on Twitter with stories of being abused by the police — who ignored their requests not only to know why they were being detained, but also requests for things such as rolling down the windows in hot police vans.

This level of neglect harkens back to the death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, or the death of Sandra Bland in Texas. In both of those instances, the police claimed that the victims hurt themselves, but the negligence shown toward the detainees makes one think that any pre-existing issue anyone might have had could only have become worse in police custody.

While Black protesters were detained abusively, an armed group of vigilantes called the Oath Keepers showed up at Tuesday night’s protests weren’t even approached initially by police and the legality of their presence had to be reviewed before the police ever asked them to leave. As usual, the threat of White violence (against Black protesters) was apparently less dangerous than the protesters’ unarmed presence.

Virtually all of this — incredibly — played out in front of global news media again, just like the first time around.

It’s been a year since the death of Mike Brown at the hands of a Ferguson police officer, and it seems as if the police there has not learned a single lesson. It is still treating unarmed Black citizens as a threat. Its attempts to “control” already peaceful situations only raise tensions higher. With the growing list of Black and Brown people being murdered by police, and with the entirety of the world watching, Ferguson is a reflection of the entire country’s inability to take any substantial move towards valuing and preserving our lives.

While the movement that expanded in the aftermath of Mike Brown’s death seems to have started very slightly changing the discussion in the country — by refusing to “let it go” — it is telling that the police in St. Louis County feel they can act with such impunity with the world watching.

That means they believe enough people in power or the general public don’t object to their behavior enough to correct it. Or that if they do object, the system will continue to protect them anyway. Sadly, that assumption is probably correct. And with Ferguson being the example of systemic racism on a smaller scale, imagine how that is playing out nationwide, off-camera.