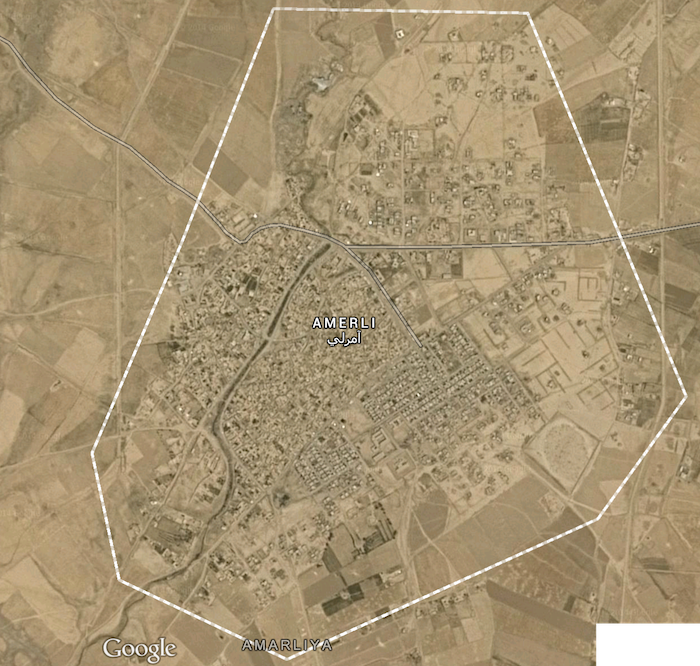

The UN is trying to draw attention to Amirli, Iraq, which ISIS has laid siege to for the past two months. The town, located several dozen miles east of Tikrit or south of Kirkuk, is home to 20,000 Shia Iraqi Turkmen living at the nexus of the Sunni Arab heartland and greater Iraqi Kurdistan — and ISIS plans to wipe them out. No Iraqi, Kurdish, or Western military force has stepped in to help. [Update: On Saturday, August 30, 2014, U.S. airstrikes began, while relief aircraft from Australia, Britain, and France dropped in supplies. Iraqi ground offensives began several days earlier.]

Though surrounded by more than 30 villages (presumably Sunni Arab) that have defected to ISIS, the town was able to seal itself off and maintains a tenuous lifeline to the outside via periodic helicopters. So far they’ve held out without much help since June — essentially just a small number of Iraqi soldiers and any weapons they had on hand — but they are now running out of food. Children are reportedly eating only once every three days.

Click on the map above to zoom out to the wider region.

Here’s one eyewitness report:

No Kurdish peshmerga, who have been fighting the Islamic State, have reached Amerli. There are only a few Iraqi soldiers who have remained after the retreat of the armed forces in June.

Haider al-Bayati, an Amerli resident, said the town is sealed off in all directions, with the nearest Islamic State position only 500 meters. With only helicopters able to bring in food, residents face starvation. Electricity has been cut off. The town has no hospital — the sick and injured must either be treated at a clinic staffed by nurses or evacuated by air.

With the helicopters only able to carry about 30 people per day, women have died in childbirth because of the lack of doctors, and according to residents, “People are dying from simple wounds because we don’t have the means to care for them.”

Dr Ali al-Bayati, who works for a humanitarian foundation has been moving in and out of the town by helicopter, added, “We are depending on salty water, which gives people diarrhoea and other diseases. Since the siege started, more than 50 sick or elderly people have died. Children have also died because of dehydration and disease.”

Former MP Mohammed Al-Bayati claimed that the town was being targeted by the Islamic State because of its Turkmen population. Noting the high-profile international effort to help the refugees of Sinjar after that town was overrun by the jihadists, he asserted, “Unfortunately, the situations are treated with two different standards”.

The question, then, is why the United States and the international community has not rallied to relieve the besieged town as they have done for the 40,000 starving Yazidis who were encircled for a week or so on Mount Sinjar.

Read more

I agree with that. There are international norms and laws against using chemical weapons, but unfortunately

I agree with that. There are international norms and laws against using chemical weapons, but unfortunately  The Economist ran what I believe to be

The Economist ran what I believe to be