A New York Times report says President Obama will destroy Syrian air defenses if they respond to the U.S. attack on ISIS, and he believes this would end the regime.

As soon as President Obama said the operations against ISIS within Syria would consist of limited airstrikes, without Syrian coordination, I wondered what was going to happen if Syrian air defenses responded to the uninvited American incursions. Are we going to destroy them like NATO did with Libya’s air defense and detection systems in 2011? Because then that’s not a limited operation anymore, and it is a direct attack on the Syrian government and military.

Sure enough, that seems to be the working plan (edit: confirmed by U.S. officials today). A New York Times article over the weekend reported on a gathering of a “a group of visitors who met with [President Obama] in the White House before his televised speech to the nation,” based on accounts by “several people who were in the meeting.”

[…] he vowed to retaliate against President Bashar al-Assad if Syrian forces shot at American planes […] He made clear the intricacy of the situation, though, as he contemplated the possibility that Mr. Assad might order his forces to fire at American planes entering Syrian airspace. If he dared to do that, Mr. Obama said he would order American forces to wipe out Syria’s air defense system, which he noted would be easier than striking ISIS because its locations are better known. He went on to say that such an action by Mr. Assad would lead to his overthrow, according to one account.

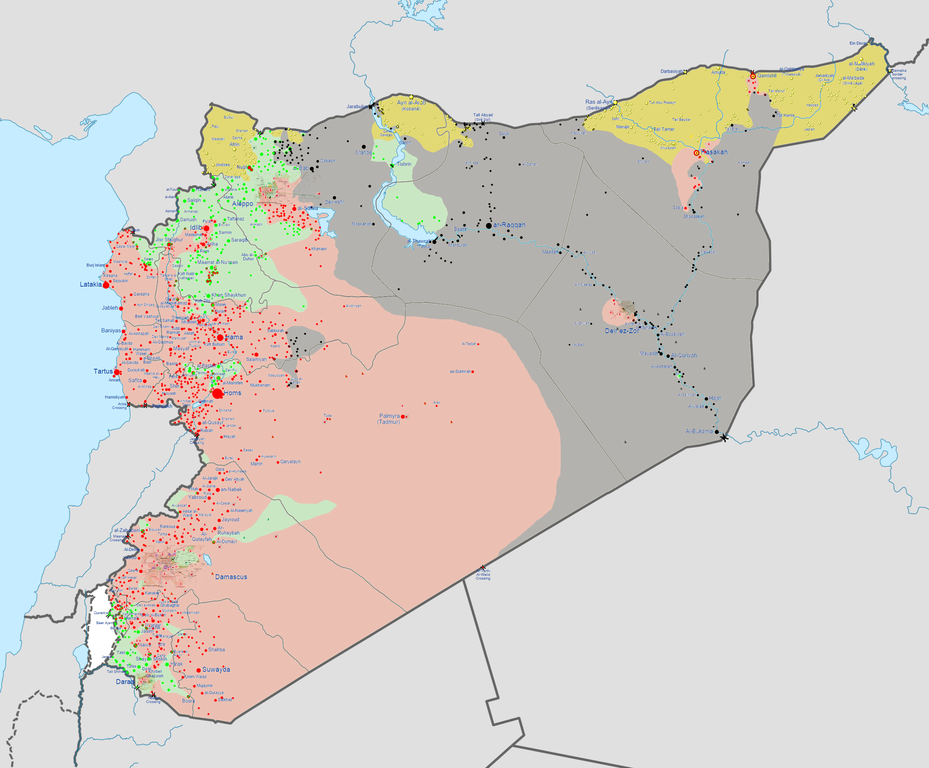

The first part of that is one of the big reasons I was and am strongly opposed to any U.S. military intervention against ISIS inside Syria. The United States’ refusal to coordinate with the Syrian regime — which makes sense diplomatically and strategically perhaps, but not tactically — is at worst goading them into hitting back at the United States and at best setting up a situation where anti-aircraft might be deployed accidentally in the heat of the moment and the confusing fog of war. Even if the regime has no plans to fire back, someone could panic upon seeing approaching bombers on a screen and start shooting anti-aircraft batteries at them. This seems like a possibility particularly at the somewhat isolated major government air base and regime-held zone near the heart of ISIS territory (see map below), where central command might be harder to contact in an emergency.

And that’s if it’s by accident. Al-Arabiya, in their coverage of the New York Times report, reiterated the Syrian government’s public determination to treat as hostile any uncoordinated efforts against ISIS within Syrian territory (longer transcript quotes are at the bottom of this page):

In an interview with CNN over the weekend, Assad adviser Bouthaina Shaaban warned against any “act of aggression” by the U.S. against Syria, while voicing readiness to work with Washington to combat ISIS.

“We are ready to be part of any coalition against terrorism, and any strike on Syria without coordination with the Syrian government is considered an aggression against Syria,” she said.

Moreover, the Times report indicates that the President noted that regime targets would be easier to hit than ISIS targets anyway — which is an awfully big detour to make from the stated goal of the upcoming operation — and claimed that the destruction of the regime’s air defense systems would cause the regime to fall. This suggests that this entire action may become, intentionally or under its own momentum and collateral consequences, the backdoor route to reboot the administration’s increasingly difficult goal of regime change in Syria.

I wouldn’t suggest that possible motive, were it not for the President’s own speech announcing the policy, in which he re-affirmed an intention to supply money, training, and weapons to the so-called “moderate rebels” in Syria. These rebels are badly, perhaps irreversibly, losing the Syrian civil war right now. Their only realistic hope of achieving victory at this point is if the Syrian regime and military suddenly collapses from some external and much larger force, such as a direct attack by the United States. So either this continued “aid to rebels” plan is a half-baked gesture or the impending operation — theoretically against ISIS, a third party — is supposed to end in a major military setback for the Syrian armed forces that is significant enough to reset the rebellion’s chances of success.

I still have no idea how the regime’s air defense systems being destroyed would, on its own, precipitate the fall of the regime to a light infantry rebellion that doesn’t seem to have had any aircraft in quite some time, if they ever did. But it would certainly make it a lot easier for an external military air power to make the decision to bomb the regime out of existence at a later date. And it might hamper the government’s ability to continue bombing rebel-held areas.

Whatever the plan here is supposed to be, it’s getting out of control before it’s even started.

Map of the Syrian Civil War as of September 13, 2014. Red = Regime, Gray = ISIS, Green = FSA, Yellow = Kurdish. (via Wikimedia)

Read more