In tributes to Singapore’s recently passed founding father, Lee Kuan Yew, much was made of the (undeniable) gains in prosperity and standards of living among the people under his strictly “managed” pseudo-democracy, as well as of how happy most residents are with their quality of life and the safety and cleanliness of their little country.

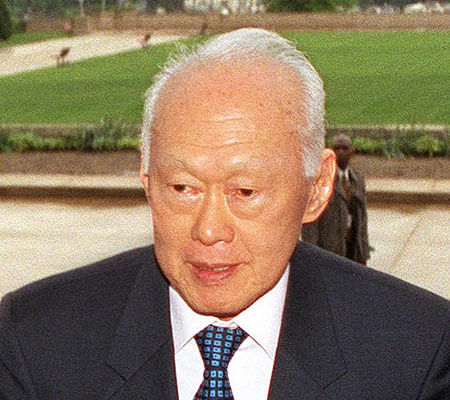

The late Lee Kuan Yew, Prime Minister of Singapore, 1959-1990; cabinet member, 1990-2012. (U.S. Government photo, 2002)

The logical extension of these commentaries has been to ask whether the success of this (almost literally) shining city on a busy coast means democracy isn’t the best way to produce a “government for the people” that actually governs well. Despite the name of this site, I’m open-minded enough to at least consider the possibility that there are other forms of government that might be equally (or even better) suited to a given society’s governance. I don’t presume to assert with certainty that Western liberal democracy is positively the be-all/end-all or the universally applicable ideal. But let’s not get too carried away by Lee Kuan Yew and the Singapore story and draw overly broad conclusions in the opposite direction either.

For a start, some of the quality of life and law enforcement issues are actually more controversial than the glowing tributes from around the world would imply; things are pretty rigid and harsh sometimes. Even the reported happiness, according to Singaporean commentator Sun Xi in a November 2013 article in The Globalist, is debatable…

But for the sake of argument, let’s stipulate that his governance of Singapore was predominantly very good and served the public interest well, despite the lack of free, fair, and open elections. Let’s say that model worked effectively in Singapore. Would that really be enough to argue credibly that Lee Kuan Yew’s legacy might undermine liberal representative democracy’s claims to serving the public interest most effectively (and therefore governing on behalf of the people best)?

I would suggest not. There’s a major component missing in such analyses. It is probably far easier to have an effective and responsive yet non-democratic government if there is also broad/near-universal agreement in that specific society about the goals and purposes of government. Democracy is less “necessary,” so to speak, for effective governance in the public interest if everyone in a society more or less agrees on what their government should be doing and what an ideal society would look like. If everyone agrees, the government just has to do those things well, and it will have succeeded. That agreement is likelier to be found in a small place like Singapore. In a vaster and more politically or culturally heterogeneous society, such as the United States, democracy is necessary to provide a stable and peaceful mechanism for sorting out competing fundamental visions of governance.

As I documented extensively in my 2012 book on the presidential nomination acceptance speeches at the Democratic and Republican national conventions, we as a country haven’t even decided on an exact definition of the American Dream — a concept that virtually everyone in the United States is familiar with and holds a notion of in their heads. We hold open elections to sort out not just the little policy issues, but the huge philosophical and cultural questions. The biggest one is probably: “Are we a country of individualists or a country of communitarians?” And everything else more or less breaks down into subcategories under general headers like that, including competing definitions of the American Dream. There’s no widespread agreement in the American population about what the purpose of our government is or what our ideal society would even look like. The closest we usually ever get to “widespread agreement” is to be able to group most people into just two big ideological camps and a hybrid, swinging center between them (all of which helps keep our two-party system naturally strong even without its procedural and structural advantages).

No U.S. leader — no matter how wise, effective, or unifying — could possibly bridge these gaps permanently and govern in a manner that did not eventually alienate a huge portion of the population. For those who agreed with him or her, the results might well turn out great and they would rate their government as “highly effective” and be content not to have to keep voting that person back into office. For those who did not agree, it would be an inescapable nightmare, and the “efficacy” of the policies would be pretty unwelcome. We have to hold open elections regularly to allow the country to keep registering its opinion on the direction to take the country, choosing between various competing visions.

Plus, just because Singapore got very lucky — with a particularly high-quality founding leader, who continued to govern reasonably well for many decades in the absence of free elections — does not mean much in and of itself. As they say, the exception proves the general rule; it doesn’t throw it out the window. Most of the time, leaders who rule for decades turn out pretty rotten. Democratic elections help reduce that danger by allowing turnover.