A recent eye-catching Washington Post op-ed, reacting to the surges of Trump and Sanders, posed the historically-based question “Are we headed for a four-party moment?” This op-ed had potential — it’s true after all that the seemingly solid two-party system in the U.S. occasionally has fragmented for a few cycles while a major re-alignment occurs — but, for some reason, it only used the 1850s and 1948 as examples (and 1948 isn’t even very illustrative in my view).

A far more intriguing additional parallel would be the 1820s (and the 1830s aftershocks). In 1820, one-party rule under the Democratic-Republican Party was fully achieved on the executive side of government, and no one opposed President Monroe for either re-nomination or re-election. It was the party’s 6th consecutive presidential win. The Federalists remained alive only in Congress, where 32 representatives (just 17% of the House membership) remained. By 1823, there were only 24 Federalists in the House. By the fall of 1824, they had all picked a Democratic-Republican faction to support.

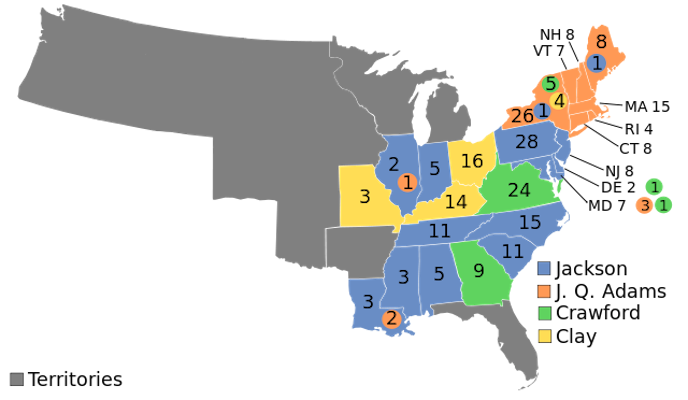

That year’s factionalism, however, was when things fell apart for single-party rule, alarmingly rapidly. The Democratic-Republican Party ran four (4!) different nominees and 3 running mates (Calhoun hopped on two tickets). Andrew Jackson won the popular vote and the most electoral votes, but no one won a majority of the electoral college. So, the U.S. House (voting in state-blocs under the Constitution) had to pick, and they chose Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, the second-place finisher.

1824 presidential election results map. Blue denotes states won by Jackson, Orange denotes those won by Adams, Green denotes those won by Crawford, Light Yellow denotes those won by Clay. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. (Map via Wikipedia)

In 1828, when Jackson set out to avenge his 1824 defeat-by-technicality, a huge number of new (but still White and male) voters were permitted to vote for the first time. Contrary to the popular mythology, not every new voter was a Jackson Democrat, though many were. To give a sense of scale for the phenomenon, both Jackson and Adams had gained hundreds of thousands of votes over the 1824 results in their 1828 rematch. At the time, that was so huge that the increases to each in 1828 were actually larger than the entire 1824 turnout had been.

In part as a result of all of this turmoil in the electorate, the party split permanently that year, creating the Democratic Party (which continues to present), under challenger Jackson, and the rival “Adams Men” trying to keep President Adams in office that year. The Democrats under Jackson won easily in 1828. A third party, the Anti-Masons, entered the U.S. House with 5 representatives.

The defeated Adams Men faction, having lost their titular leader, became the Anti-Jacksons — and were officially named National Republicans in 1830. That year, in the midterms, the Anti-Masons picked up more seats, to hold 17, while a 4th party (under Calhoun) of “Nullifiers” sent 4 representatives. But Jackson’s Democrats held a clear House majority.

The large influx of new voters also still needed to be managed, particularly by the opposition. The three big (or sort of big) parties in 1832 — Democrats, National Republicans, and Anti-Masons — held national conventions (all in Baltimore) as part of this democratization and party-organization push. Democrats, however, still clearly held an organizing advantage.

They triumphed again in 1832, which had seen a 3-way race between President Jackson, the National Republicans, and the Anti-Masons. This repeated failure (at that point three consecutive elections lost at the ballot box, if you remember the popular result of 1824!) and the continued growth of the Anti-Masons and Nullifiers in Congress prompted the desperate need for re-organization in the opposition. The National Republicans merged into the Whig Party in 1833, along with various other political clusters and small parties that were left out of politics by either the Jackson faction or the destruction of the Federalists decades earlier.

Unfortunately, this attempt at merging the opposition factions into the Whig Party went poorly at first. The Democrats still captured 59% of the House seats in the 1834 midterms, despite the third and fourth parties finally receding (to the Whigs’ advantage). Then, worse, the 1836 presidential election saw Democratic Vice President Martin Van Buren win a staggering five-way general election race, defeating almost by default the four Whig nominees — but with just 50.83% of the popular vote and an electoral college margin above the crucial majority-line of just 22 electors.

Assuming (and I realize it’s a big assumption for the time) that the election was above-board and not bought, had just 4,300 Pennsylvania voters gone against Van Buren, flipping 30 electoral votes, the 1836 presidential election would have landed back in the U.S. House like 1824. (Or, if you prefer, 7,200 Virginians could have flipped for 23 electoral votes. Even Van Buren’s home state of New York was pretty close and would have prevented a majority, had it gone against him. He lost it four years later when he was defeated.)

However, the 1836 election, while a presidential fiasco for the Whigs, did put the Whigs just 22 seats short of a House majority, which finally proved its viability as a unified national opposition party against the Democrats. The other two parties receded even further. After the 1838 midterms, the Democrats held the chamber by just 3 seats.

Not until 1840 did the opposition (Whigs and beyond) get its act together and nominate only one presidential candidate against the incumbent Van Buren, which proved a briefly successful formula. In addition to taking the White House, the Whigs also finally captured the U.S. House majority and eliminated or adopted any rival opposition parties’ candidates. Only 2 representatives were even elected as independents.

But, for the period from 1824 to 1839, or four presidential cycles and nine Congressional elections, there was essentially not a stable 2-party system in the United States — and even a mere 3 factions was unusual. At the end of it, there had been a total re-alignment and the emergence of essentially two new major parties.

The period was a chaotic response to a rapidly changing and more engaged electorate, hellbent on reducing elite power and destroying many longstanding governmental and financial institutions. That was something the super-wealthy populist slaveowner Andrew Jackson harnessed very effectively, when he wasn’t challenging people to single combat.

I didn’t even realize this post was going to end in an inadvertently very specific Donald Trump comparison when I started it. Go figure.