(This essay contains plot details.)

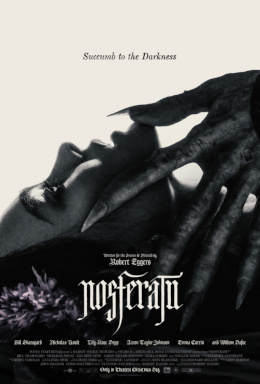

Nosferatu is the latest gothic horror film from the director and screenwriter Robert Eggers (The Witch, The Lighthouse, The Northman), whose films often viscerally evoke a popular mindset and sensibility of a bygone era that we cannot genuinely grasp or relate to from our 21st century world. Where so many “period pieces” released in the present-day simply project backward a present-day worldview and belief system without regard to anachronism, Eggers typically goes to great pains to try to depict a past that is completely alien to us and whose people would not be able to understand any of the ways in which we comprehend or parse our own world today.

An unfamiliar familiarity

His new film, ostensibly about a vampire moving to Germany at the dawn of the Victorian Era, adapted from the 1922 German film of the same name (itself a reinterpretation of the 1897 Bram Stoker novel Dracula) lands in a particularly interesting setting for us as modern viewers. His 2015 film “The VVitch: A New England Folktale” is set in the 1630s, early in the age of Modern English (the language of the film), which is only fleetingly legible as “modern” because it takes place beyond the periphery of “civilization” in the second century of Modernity. By contrast, Nosferatu is set (in part, at least) much closer to a world we feel we can recognize and understand in the form of urban Germany in 1838. But even in these scenes – before we get to the rural Carpathian settings – something remains completely “off” to our 21st century eyes. There is a discomfort here that might even read to the audience as erroneous filmmaking, in contrast with our ability to integrate the discomfort more readily with 1630s New England or 10th century Iceland because they are so overtly unfamiliar.

We think we know life in the late 1830s. The fictional German city of Wisborg, one of the two settings of the film, is a modern capitalist city in Europe on the brink of heavy industrialization. The late 1830s is just about within the family memory of many of us living today. So, as the film unfolds and we see certain portrayals on the screen, it feels out of time and place in a peculiar way. But the reality of Victorian Era society is that it was rife with the type of contradictions that feature so prominently in the popular gothic fiction of the day. Despite the constant self-juxtaposition of the modern, enlightened rationalism of urban, capitalist Europe with the backwards agrarianism of the barbarous lands of the Balkans and the Russian Empire, the high society of cities in Europe and the United States were obsessed with the occult and faeries and all manner of supernatural throwbacks.

Certainly, they managed to industrialize, systematize, and mass produce what was once colorful local folklore and superstition over the course of the 19th century, and perhaps they were not as ready as medieval and early modern counterparts to sincerely blame things on witchcraft, but they were nevertheless completely fascinated by these ideas. And they never stopped thinking about and talking about death – perhaps unsurprising in an increasingly urbanized world where cities still killed more people than they birthed each year, only continuing to grow by strangling the traditional way of life in the surrounding countryside and sucking economic migrants into the core. Young women and girls were especially vulnerable – and usable – in this shifting world.

Ellen

Our heroine of the film, the newly married Ellen Hutter, is perhaps the most challenging and complex role in the story, and it can be difficult to say conclusively whether Lily-Rose Depp pulls it off successfully, although she does deliver some incredible performances in a number of scenes. Her character is a layered figure who has been incredibly lonely for much of her life, with decidedly mixed results in trying to fill that loneliness.

Like many Victorian women of society, even beyond any possible supernatural abilities or difficulties with seizures, Ellen is always on the verge of an explosive emotional outburst – either because of a lifetime of traumatic and controlling abuse or the constant, ambient social repression of her true nature and desires, or all of it together. Throughout the film, there is a tension between physically restraining or incapacitating someone against their will for their own safety (and social conformity) versus allowing them to do what their instinct tells them, a literal representation of the implied social repression. She feels very deeply about everything, and she seems to feel emotions that are not always aligned to what she understands is the socially correct emotion for a given situation. Prof. Franz tells her that maybe in an ancient world, she would have been a venerated and powerful priestess by virtue of all the animalistic characteristics and supernatural connections that make her struggle so much in 1838. Instead she is at the mercy of everyone else in all but a few fleeting moments, with all her choices constrained or coerced. From childhood abandonment and manipulation to her cruel confinements against nightly sleepwalking to the systematic annihilation of her friends, and at last to her final exsanguination, it is not fair or deserved what happens to her, but it simply is. Her husband, Thomas, constantly attempts to have an effect on his situation through bold personal action, typically in vain (subverting what another director/writer might have depicted), while she accepts that she cannot overcome the forces acting upon her. In about 10 years from the events of this story, everyone like him will be crushed in the failed 1848 German Revolution and flee to the United States, leaving behind a much more fatalistic German population.

Ellen would have grown up shortly after the Napoleonic Wars in the era of Grimm’s Fairy Tales and the German Romanticism movement to define a German national culture in opposition to both the French Enlightenment and the former Holy Roman Empire’s fragmentary feudalism. She is born into a socially patriarchal “Fatherland” that has not yet come together as a singular nation-state, a realm that is a hodge-podge of bustling trade centers and heavily forested principalities still operating under the old ways. A consciousness is emerging that this collection of territories, still recovering from two centuries of other states’ armies ravaging and pillaging back and forth from all four compass points, would be better off (and treated better) together, but so far it is still not taken seriously. Its modernizing impulses are explicitly set against the continued backward features that middle class and wealthy German people of the age know still remain but wish to be rid of.

Ellen notes that her father lost patience with her childhood development and peculiarities and eventually denounced her for communing with faeries – a popular fixation of the 19th century urban middle class as they became increasingly disconnected from the countryside, which was seen as the reservoir of distinctive national identity. (Later in the film, her host Friedrich denounces her several times for her apparent occult connections, again making reference to faeries.) She also says that her father accused her of being a changeling. The 19th century saw a fresh wave of hysteria around the notion that supernatural beings were routinely swapping out ordinary children for mentally defective substitute children who had intellectual disabilities or mental illnesses, things along the lines of her epilepsy. It’s hard for us today to think back six or seven generations to a seemingly modern setting and understand that many educated people believed this as fervently as a medieval peasant.

Like any good gothic horror, the subtext of the supernaturalism in this story is that the past is not really dead, that there is no linear progression of human development, and that education alone cannot account for everything.

Thomas

Ellen’s new husband, the young striver Thomas Hutter, represents the emerging class of highly educated clerks and agents who (along with junior attorneys) grease the wheels of capitalism but are not themselves owners of capital or members of the bourgeoisie. Karl Marx, who published The Communist Manifesto just 10 years after the setting of this film, largely neglects to comment on or analyze the role and importance of this class in his descriptions of the rising world order of places like Germany, Britain, and France as industrialization enters full swing. Marx wrote much of his work when clerk-type employees and middle managers still represented a pretty marginal segment of the population. Their importance exploded with the rise of telegraphy, cheap paper production, filing cabinets, and typewriters a bit later in the 19th century. His analysis took place in an era where clerks were still more like the titular character of Melville’s 1853 “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” tasked with copying records by hand, and it is perhaps easy to overlook their growing critical function.

Back in 1838, our somewhat hapless would-be protagonist Thomas, is seeking to enter this world of clerks. He has received a good education, but he is not wealthy. He is from the liberal intelligentsia, not the conservative bourgeoisie or landowners, but he will be working on their behalf and doing their bidding, as his career. What he desperately wants is financial security, steady employment, and career advancement. His new wife, Ellen, begs him not to take the special mission appointed to him by his new employer, a real estate broker, to travel to the Carpathian Mountains to hand-deliver a contract for a property sale in Wisborg. He insists on leaving her behind to undertake this task because the boss, Herr Knock, has explicitly promised that it will guarantee his job and better compensation. But here is the fundamental problem of the role of the clerk: although they are white-collar, educated workers and not owners of capital or titles, they are totally controlled by the ruling classes and in thrall to them, not only serving those interests but greedily acting against their own long-term self-interests for the prospect of short-term monetary advantage. Marx didn’t realize just how many of these guys there were about to be across Europe and the United States within just a few decades, as capitalism jumped to national and multinational corporate scales. (When you see Franz and Sievers rifling through stacks of hand-copied papers and books to find information on Knock’s demonic master, it’s easy to see why the administrative middle management seemed somewhat less important to an early analysis of capitalism and class struggle.)

Thomas and his boss (who, along with his shop full of other old white-haired clerks, stands in for the earlier age of fixers and contract facilitators of feudalism) are quite literally servants to a demonic figure, the Nosferatu, Count Orlok. But a man like Thomas is also just as much in hock to his creditor and benefactor, the wealthy capitalist Friedrich Harding, a shipyard owner. Long before Thomas signs a nefarious, supernatural contract with Count Orlok (either under the influence of hypnosis or induced by a simple bag of coins), he is already locked into some kind of financial arrangement with Friedrich. Ellen expresses at various points of the film, with characteristically strong emotions, that she doesn’t feel they needed more income or material possessions, but her protests are unable to penetrate the striving avarice of her husband, who justifies his singular focus as being for her benefit.

Count Orlok

Thomas journeys to one of the Romanian lands – perhaps Habsburg Transylvania or one of the Danubian Principalities recently occupied by the Russian Empire as protectorates after centuries of Ottoman protection – where he encounters a kaleidoscope of truly “Old World” cultural practices from Roma peoples and Romanian peasants to a semi-Asiatic feudal lord (who is also a vampire, of course) to the local Eastern Orthodox priest and nuns. All of this Carpathian hinterland, located at the crossroads of the Habsburg, Ottoman, and Russian empires, a place where slavery itself still lingers for the Roma, stands in contrast with his familiar world of a modern, Lutheran city like Wisborg, with its merry Christmas trees and Christmas markets and women who dress in the fashions of the newly reigning Queen Victoria of Great Britain, herself soon to be one half of a young, besotted German couple.

The grotesque and rotting Count Orlok – in contrast with the latest courtly trends of the liberal, modern nobility to the north – sports a 15th century Balkan boyar moustache and mouldering fur hat inspired by early portraits of the Wallachian Voivode Vlad III (the real Dracula), whose notorious purges included brutal impalements of ethnically German villagers in his Romanian lands and thousands of Turks and Bulgarians nearby. (Bill Skarsgård delivers an unforgettable performance from start to finish.) This is a fitting historical personality to emulate so closely in this remake, quite distinct from the 1922 appearance and manner of the Nosferatu character, because the salacious tales of that ruthless Romanian ruler were an early popular print subject in Germany by the end of the 1400s.

The educated, liberal Thomas struggles to maintain the conventions of feudalism, being admonished by Count Orlok for failing to address him as “my lord” instead of “sir.” This is where he begins to understand the trap he has walked into. He has underestimated the continued death grip of the dying relics of feudalism and serfdom in 19th century Europe and its ability to cause damage. It should be a decrepit throwback that is powerless and only formally titled, yet it holds hypnotic power and never seems to die away. One of Orlok’s supernatural abilities is control of plague-bearing rats, which he soon brings with him to Wisborg by sea, an apt metaphor for the unending cyclical recurrence of something medieval well into the modern era.

Karl Marx was quite fond of gothic fiction metaphors in his own commentaries on political economy of Europe in the mid-19th century, not only comparing communism to a haunting specter, but also frequently describing the capitalist class as parasitic, blood-sucking vampires feeding off the labor of the workers and most especially feeding off children who are forced to work. (In one reference in Das Kapital, mentioned in the previous linked paper, Marx actually makes a non-supernatural reference in passing to the aforementioned Vlad “The Impaler” Dracula’s forced labor practices with Romanian serfs.) Marx was also quite interested in the length of the working day and the division of daytime and nighttime hours because he saw the exploitation of the laboring classes as robbing them not only of fair wages or their health, but also of their time and their personal lives. The plot of Nosferatu certainly hinges upon daylight and nighttime, although inverting them in terms of when people’s lifeforce is being drained.

In this film’s story, of course, the literal vampire is the feudal Count Orlok, whose hold over the local peasantry (whose work has created his wealth) is beginning to slip, and he is prepared to make the jump to modernity and move to the big city to feast upon his new favorite, a middle class girl, instead of exasperatingly superstitious and defensive peasants and Roma nomads. But also figuratively, the other rich, parasitic ruling class, the one whose burghers built these cities, are apparently prepared to accommodate his arrival, especially since it won’t inconvenience them for him to move into a derelict mansion. Money is money.

Friedrich

Friedrich, the wealthy shipyard owner portrayed superbly by Aaron Taylor-Johnson, represents the actual capitalist bourgeoisie, unlike clerk Thomas. He repeatedly demonstrates that he is quite socially conservative. He also stands in for the attitudes of many of the powerful capitalists towards feudal figures like Count Orlok. The aristocracy poses an acknowledged problem for the capitalists, but not one that they are prepared to overthrow if they can simply wait it out and supplant its role in society. He will never be a revolutionary. This foreshadowing of the capitalists taking the place of the feudal lords is depicted in the way Friedrich behaves toward his socially inferior friends and his wife, Anna, especially after she dies and he violates her in the crypt in a manner that is functionally the same as and visually similar to the sexual violations committed by the Nosferatu. His rising ruling class will be the new vampires, regardless of the fate of the feudal lords.

Throughout the film Friedrich engages in noblesse oblige, up to a point, but he is entirely self-interested if generosity causes him any trouble, and he will just as soon turn out his friends. Had things worked out even a little differently in the film, he probably would have called in the loan to Thomas that he previously said not to worry about.

Friedrich is also intriguingly differentiated from the feudal Count Orlok in his indicated willingness, as all grand bourgeois capitalists are, to relocate at a moment’s notice if things go sideways, in contrast with Orlok whose feudal power and success is so literally tied to the land that he must travel (with great difficulty) by bringing his home soil with him.

Sievers and Franz

Dr. Wilhelm Sievers and his mentor Prof. Albin Eberhart Von Franz, represent, together, the contradicting push and pull of the modern and anti-modern tendencies of the emerging German national identity. They are both educated and both working to find breakthroughs to solve society’s problems, but Dr. Sievers is looking for modern, rational, scientific methods (such as his humane asylum plans) to soften but not overturn the status quo and Franz is looking for alchemical ideas in the past that could fundamentally transform things as they are into something else, in response to a gnawing feeling over many years that something terrible is developing. They do not always agree on the approach but their goals are broadly similar, and they work well together. They both do not have much time for 18th century French Enlightenment. Although Voltaire is not mentioned in the film, that sarcastic Parisian commentator of the Enlightenment wrote a scathing dictionary entry on the absurdity of persistent belief in vampires by people who should know better. But as Prof. Franz repeatedly points out, clearly this vampire is real anyway. Karl Marx would see his point (and in fact Voltaire also commented on the same parasitic, blood-sucking tendencies of the wealthy).

Prof. Franz is more explicitly critical than Dr. Siever of the forward march of early industrialization, perhaps fairly deriding the modernity of gas lamps as giving people a false sense of the dark and mysterious world of the past being dead and gone. 1838, as it turns out, is not so close to our modernity as we might have imagined. It was a cruel and blood-drenched backwards place where the supernatural could be both sincerely believed and eagerly consumed in marketable fiction by the same people.

What gothic horror always reminds us is that however incomprehensible and distant the past might seem to us, it can always return again. We in our cities are not more immune, at the end of 2024, to the resurgence of and latent persistence of backwards and superstitious beliefs. It’s getting dark out there again.