The irony of the internet age and the rise of social media under autocratic states is that it not only hasn’t brought an end to traditional replacement-of-reality-with-alternate-reality propaganda (à la the Soviet Union’s totalitarian media) and toppled all the dictators, but it has actually provided new opportunities for some of the propagandists. Propaganda is not just co-existing but flourishing, at the moment, even in places with ample internet access.

Person of the Year

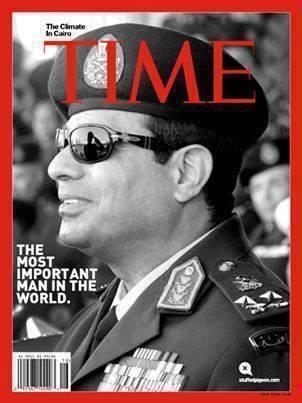

Case in point: Egyptian government propagandists on state-run and pro-coup television were so eager to promote their new dictator, General Sisi, that they convinced everyone that Egyptians could control the outcome of TIME magazine’s person of the year selection and ordered them all to vote for him in the magazine’s online reader poll — which has no affect on the final choice for the magazine (which the editors pick). More Egyptians voted in the global internet poll, open to anyone, than the number of Americans or Indians who voted. Then when General Sisi won that reader poll, Egyptian media produced a fake cover of TIME and reported (falsely of course) that he had been officially chosen by the magazine as Person of the Year.

Obviously, given their easy access to outside media, most internet-using Egyptians are probably well aware of the distinction, whether or not they voted for him in the poll. It’s worth remembering, however, that a lot of Egyptians still get their news from television media and, unlike their Twitter-savvy brethren, aren’t necessarily exposed to alternate sources of information. So if the TV says TIME magazine picked their nation’s leader as the global Person of the Year, and shows a cover to prove it, then they might not know otherwise.

American TV News

Television is by nature an authoritative, one-way medium that many viewers can’t contradict or fact-check easily (and tend not to, even if they can). Thus, propagandists can exert a heavy influence without much to challenge them. And in the modern era, they can couple it with the power of the internet rather than being undermined by it.

The Egypt story might seem provincial and irrelevant to us in the United States, but let’s not forget that a majority of Americans — particularly from the older generations — still get their news from television each day. The influence of TV news producers, while substantially more open to challenge in the United States than in Egyptian state media, is still a powerful force with a rigid narrative.

Viewers receive a narrow (partly by nature of the time-restricted format) and often repetitive message and are strongly encouraged to put their trust in the networks — local, national, or cable — that they are being told The Truth. Network brands are marketed like other products through heavy promotion. The promos urge people to maintain high brand loyalty to a particular delivery service of what is (theoretically) open information that should — if it’s really The Truth, as advertised — be more or less the same across brands.

The Fox Delusion

Fox News Channel, of course has taken this philosophy much further. They brag that they are the highest-rated cable news network … after years of convincing viewers — who skew older and count on television to be factually accurate — that the news world outside (except for right-wing talk radio, of course) is filled with lies and treachery, and that only Fox News Channel and its hosts’ radio shows are able to bring you The Truth. So everyone on the conservative end of the spectrum jumped on the bandwagon long ago and stayed put, resulting in its rise to the number one spot (while liberals split over a range of sources). For a regular viewer, adjusting that dial away from Fox News means being exposed to the “liberal media” conspiracy beyond.

Fox News Channel broadcasts are riddled with demonstrable errors — not just in analysis, but in basic statements of empirical, encyclopedic facts — as many a media fact-checking website has shown every day. Its viewers know better by now than to check outside the channel or its partners for the facts, though, so there is little danger they will be exposed to reality. When they go to vote in U.S. elections, they are doing so based on information received almost entirely if not solely from one news universe that has built all its analysis upon totally fabricated underlying facts. It’s not just skewed interpretations being delivered to viewers, but even foundational “facts” lacking in truth.

All this holds true even in an age of easy access to a literal world of factual information, via the internet. The internet, for a Fox viewer, instead of a source of contradicting reality, becomes a network of websites affiliated with Fox News or run by other devotees and like-minded ideologues.

Thus, as I have discussed extensively before, Fox News, right-wing talk radio, and the conservative blogosphere have established an entire unchallenged, closed-loop parallel universe of news “reality,” much in the way a totalitarian government’s state media would. And just as with Egyptian TV’s fake TIME magazine Person of the Year cover, Fox News Channel is able to propagate its elaborate fiction through traditional means, with help from the internet, rather than being genuinely subverted and exposed by the internet, as we might have expected.

What does the future hold?

The internet, social media, and freer access to information around the world will undoubtedly play a major role in opening societies and exposing fictions presented as news — and certainly the U.S. internet community has already been ripping apart fraudulent news stories in the traditional media for many years and forcing corrections (from outlets that aren’t trying to create a parallel reality).

But for the moment, at least, the rise of the internet is not the cure-all for propaganda, whether on U.S. cable or on authoritarian governments’ TV stations. The meeting of the internet and propaganda isn’t like throwing water on the Wicked Witch of the West. The narratives and fictional worlds of propagandists don’t dissolve instantly in the presence of access to information. But eventually, they will crumble.

The interim period will not be without consequences. How do people, including Egyptians or Fox News fans, react when confronted by the harsh light outside the cave? Ultimately this confrontation will inevitably occur, as it always has, despite the propagandists’ efforts to steer people to favorable sources. Whether the clash with reality occurs in the form of the loss of U.S. election if you were under the false impression that everyone agreed with the worldview Fox News nurtured in you, or in the form of realizing at newsstands in a few weeks that TIME magazine hasn’t put Dear Leader on the cover after all, people seem react in two ways.

The first reaction is turning in anger to wild conspiracy theories that explain the disjunction — i.e. that inscrutable minority forces must be controlling outcomes — and encourage extreme responses to “correct” the conspiracy — i.e. that the opposing faction must be destroyed. The second reaction is accepting that the propagandists have misled their audience about The Truth outside.

Sadly, many people find discovering themselves massively wrong or realizing they have been to duped to be extremely embarrassing or humiliating. (Being manipulated is something that happens to other people.) And so these people generally resist accepting they have been conned at all costs, even if it means embracing the extreme conspiracy theories and doubling down on their misguided beliefs. And that’s when the politics in a country get really scary.

Sometimes the role of government isn’t about the really big things. Sometimes, it’s just about the little things that affect everything else.

Sometimes the role of government isn’t about the really big things. Sometimes, it’s just about the little things that affect everything else.