Guest post by Etienne Borocco in France: Europe went to the polls last weekend and elected a lot of fringe politicians to the EU parliament. So what does it all mean?

Traditionally, the turnout is low in the European elections: only about 40%. This year, it was 43%. The functioning of the European Union is quite complex, as depicted in the chart below:

Illustration 1: Flowchart of the European political system (Credit: 111Alleskönner – Wikipedia)

Why the EU elections matter — and why the media and most voters ignore them:

The directly elected European parliament and the unelected Council of the European Union (Council of Ministers) co-decide legislation. The European Commission has the monopoly of initiative, i.e. it is the only one to initiate proposals. The European Parliament can vote on and amend proposals and has the prerogative to vote on budgets. If the Council of European Union say no to a project and the parliament yes, the project is rejected. So the parliament is often described as powerless and its work, which is often about very technical subjects, does not hold the media’s attention very much. Consequently, the European elections to vote for Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) have a low turnout – and a lot of electors use it to express concerns about national subjects.

For example in France, 37% of the registered voters answered that they would vote by first considering national issues and 34% also answered that they would vote to sanction the government. The proportional vote system (in contrast with America’s first-past-the-post Congressional elections, for example) gives an additional incentive to vote honestly according to one’s opinion, rather than strategically for a major party (or major blocs of allied parties in the case of the EU parliament).

The May 25th European election was a shock in the European Union, even after the small parties had long been expected to do well. The biggest parliamentary groups in the European parliaments lost seats, while parties that reject or contest the European Union rose dramatically.

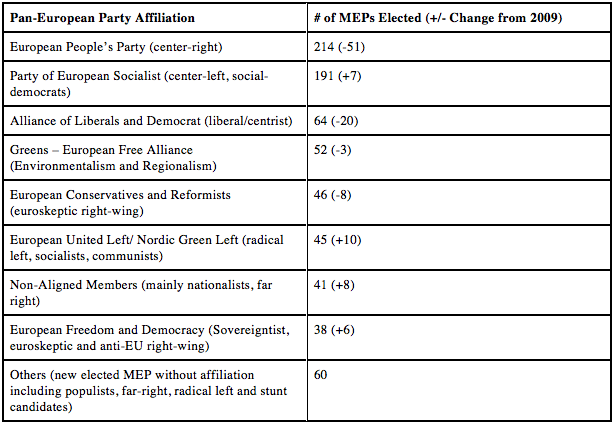

In Denmark, in the United Kingdom, and in France, the anti-euro right wing took the first place. It was particularly striking in France because unlike the traditionally euroskeptic UK or Denmark, France was one of the founding countries of European integration and is a key member of the eurozone (while the other two are outside it). The Front National (FN), which has anti-EU and anti-immigration positions, gathered one quarter of the vote in France. Non-mainstream parties captured significant shares in other countries, although they did not finish first.

Populist/Right-wing/Anti-EU party vote share by country in the 2014 EU elections. Data via European Parliament. Map by Arsenal For Democracy.

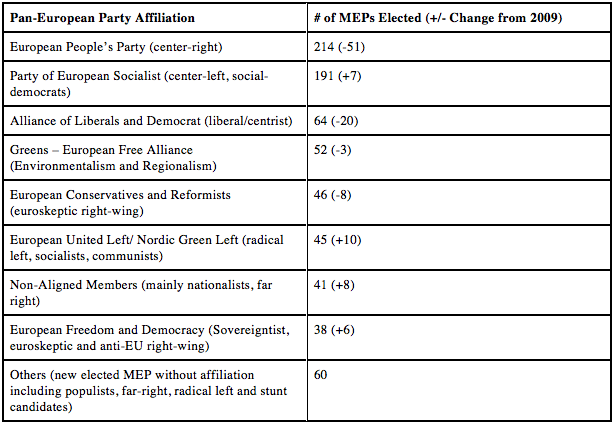

The new seat allocations:

Let’s look at the gains and losses. With the exception of the socialist bloc, the traditional parties lost seats — particularly in the mainstream conservative EPP and centrist ALDE blocs, which virtually collapsed. The May 25 European parliamentary elections also marked the notable appearance of new populist right-wing parties in Eastern Europe, among the newer member states. For example, two conservative libertarian parties (movements that are a bit like a European version of Ron Paul) won seats – the KNP in Poland and Svobodní in Czech Republic. Moreover, the national government ruling parties were hugely rejected in most countries, whether by populist fringe parties dominating (as in France, the UK and Denmark) or by the main national opposition parties beating the ruling parties.

Among the non-aligned (NA) members elected, if we exclude the six centrists MEPs of the Spanish UPyD (Union, Progress and Democracy), the 35 MEPs remaining are from far-right parties.

Among the 60 “Others” MEPs, there are 3 MEPs of Golden Dawn in Greece and 1 MEP of the NPD in Germany, both of which are neo-Nazi parties. The NPD was able to win a seat this year because Germany abolished the 3% threshold. With 96 seats for Germany, only 1.04% of the vote is enough to get a seat. The Swedish Democrats (far right) got 2 seats. In total, 38 MEPs represent far-right parties, out of a total of 751 MEPs.

So why do observers talk about an explosion of far right?

Beyond those scattered extremists, the vote for the more organized euroskeptic, hardcore conservative, and far right parties all increased sharply. The UKIP in UK (26.77%, +10), the National Front (FN) in France (24.95%, +18), the Danish People’s Party (DPP) (26.6%,+10) and the FPÖ in Austria (19.7%,+7) rocketed from the fringe to center stage. The UKIP, the FN, and the DPP all arrived first in their countries’ respective nationwide elections, which is new.

Other parties elsewhere did not come in first but performed unexpectedly (or alarmingly, depending on the party) well this year. For example, although the Golden Dawn only won three seats from Greece, they did so by winning 9.4% of the country’s vote, even as an openly neo-Nazi party. The Swedish Democrats (9.7%, +6.43) and the Alternative For Germany (7%, new) also made a noteworthy entry in the parliament.

Their shared characteristic of all these parties, regardless of platform and country of origin, is that they are populist in some way.

True, under the word “populism,” a lot of different parties are gathered and their ideologies may vary. While most of these parties claim to be very different, we can, nonetheless, put everyone in the same basket for the purposes of this analysis, to understand why the results were so shocking. Their core point in common is that they all claim represent the people against “the elite” and “Brussels” which embodies both “evils”: the EU and the euro.

We could use the following system to classify like-minded populist parties:

Read more