Guest post by Etienne Borocco in France: Europe went to the polls last weekend and elected a lot of fringe politicians to the EU parliament. So what does it all mean?

Traditionally, the turnout is low in the European elections: only about 40%. This year, it was 43%. The functioning of the European Union is quite complex, as depicted in the chart below:

Illustration 1: Flowchart of the European political system (Credit: 111Alleskönner – Wikipedia)

Why the EU elections matter — and why the media and most voters ignore them:

The directly elected European parliament and the unelected Council of the European Union (Council of Ministers) co-decide legislation. The European Commission has the monopoly of initiative, i.e. it is the only one to initiate proposals. The European Parliament can vote on and amend proposals and has the prerogative to vote on budgets. If the Council of European Union say no to a project and the parliament yes, the project is rejected. So the parliament is often described as powerless and its work, which is often about very technical subjects, does not hold the media’s attention very much. Consequently, the European elections to vote for Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) have a low turnout – and a lot of electors use it to express concerns about national subjects.

For example in France, 37% of the registered voters answered that they would vote by first considering national issues and 34% also answered that they would vote to sanction the government. The proportional vote system (in contrast with America’s first-past-the-post Congressional elections, for example) gives an additional incentive to vote honestly according to one’s opinion, rather than strategically for a major party (or major blocs of allied parties in the case of the EU parliament).

The May 25th European election was a shock in the European Union, even after the small parties had long been expected to do well. The biggest parliamentary groups in the European parliaments lost seats, while parties that reject or contest the European Union rose dramatically.

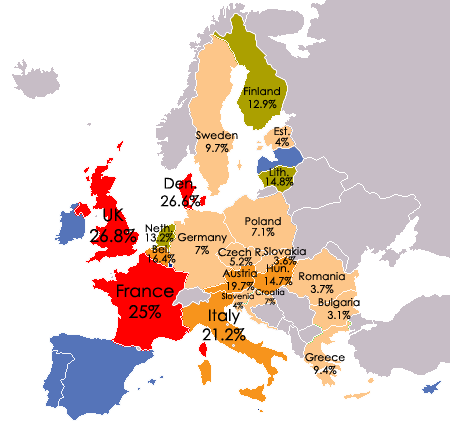

In Denmark, in the United Kingdom, and in France, the anti-euro right wing took the first place. It was particularly striking in France because unlike the traditionally euroskeptic UK or Denmark, France was one of the founding countries of European integration and is a key member of the eurozone (while the other two are outside it). The Front National (FN), which has anti-EU and anti-immigration positions, gathered one quarter of the vote in France. Non-mainstream parties captured significant shares in other countries, although they did not finish first.

Populist/Right-wing/Anti-EU party vote share by country in the 2014 EU elections. Data via European Parliament. Map by Arsenal For Democracy.

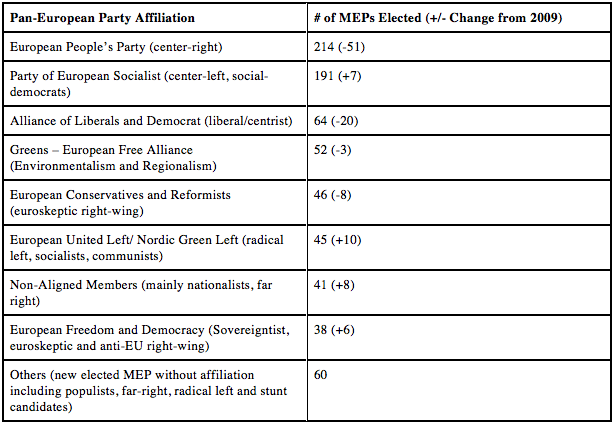

The new seat allocations:

Let’s look at the gains and losses. With the exception of the socialist bloc, the traditional parties lost seats — particularly in the mainstream conservative EPP and centrist ALDE blocs, which virtually collapsed. The May 25 European parliamentary elections also marked the notable appearance of new populist right-wing parties in Eastern Europe, among the newer member states. For example, two conservative libertarian parties (movements that are a bit like a European version of Ron Paul) won seats – the KNP in Poland and Svobodní in Czech Republic. Moreover, the national government ruling parties were hugely rejected in most countries, whether by populist fringe parties dominating (as in France, the UK and Denmark) or by the main national opposition parties beating the ruling parties.

Among the non-aligned (NA) members elected, if we exclude the six centrists MEPs of the Spanish UPyD (Union, Progress and Democracy), the 35 MEPs remaining are from far-right parties.

Among the 60 “Others” MEPs, there are 3 MEPs of Golden Dawn in Greece and 1 MEP of the NPD in Germany, both of which are neo-Nazi parties. The NPD was able to win a seat this year because Germany abolished the 3% threshold. With 96 seats for Germany, only 1.04% of the vote is enough to get a seat. The Swedish Democrats (far right) got 2 seats. In total, 38 MEPs represent far-right parties, out of a total of 751 MEPs.

So why do observers talk about an explosion of far right?

Beyond those scattered extremists, the vote for the more organized euroskeptic, hardcore conservative, and far right parties all increased sharply. The UKIP in UK (26.77%, +10), the National Front (FN) in France (24.95%, +18), the Danish People’s Party (DPP) (26.6%,+10) and the FPÖ in Austria (19.7%,+7) rocketed from the fringe to center stage. The UKIP, the FN, and the DPP all arrived first in their countries’ respective nationwide elections, which is new.

Other parties elsewhere did not come in first but performed unexpectedly (or alarmingly, depending on the party) well this year. For example, although the Golden Dawn only won three seats from Greece, they did so by winning 9.4% of the country’s vote, even as an openly neo-Nazi party. The Swedish Democrats (9.7%, +6.43) and the Alternative For Germany (7%, new) also made a noteworthy entry in the parliament.

Their shared characteristic of all these parties, regardless of platform and country of origin, is that they are populist in some way.

True, under the word “populism,” a lot of different parties are gathered and their ideologies may vary. While most of these parties claim to be very different, we can, nonetheless, put everyone in the same basket for the purposes of this analysis, to understand why the results were so shocking. Their core point in common is that they all claim represent the people against “the elite” and “Brussels” which embodies both “evils”: the EU and the euro.

We could use the following system to classify like-minded populist parties:

The Sovereigntists: They feel their home countries are losing national sovereignty and are thus against the European Union and of course against the Euro. The sovereigntist MEPs from various countries and national parties serve together in the European Parliament under the bloc called “Europe of Freedom and Democracy” (EFD) led by Nigel Farage. Back home he is also the leader of Britain’s leading sovereigntists, the UK Independence Party (UKIP). The EFD also includes hardcore conservatives and some parties, such as the Danish People’s Party (DPP) or Finns Party (previously known as True Finns), generally considered to be far right.

The EFD is a strong supporter of Vladimir Putin and denounced what they called “the interference of the EU in Ukraine.” In fact, the leader of the Lithuanian Party Order and Justice, Rolandas Paksas, is a former Lithuanian president impeached for links with the Russian mafia. Nearby, the Conservative People’s Party of Estonia is another sovereigntist party. It is quite similar of the Danish People’s Party, in that they are against the EU, they play the role of the far-right party in their country, their platform is quite vague (as always with populists) and they support membership in NATO. The last point is very crucial and it differentiates the euroskeptic sovereigntists substantially from nationalists who are predominantly anti-American. It is also a big contradiction (and not the only one) among sovereigntists to be both Atlanticist and pro-Russia. In fact, they are for whatever that may weaken the EU.

As is plainly evident, there is not an overwhelming ideological unity among sovereigntists, but it is very similar to the tea-party movement in the United States. Sovereigntists are against European institutions but they are not opposed to free trade. The UKIP wants a free trade agreement in Europe like is the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). Others want to go back to the European Economic Community (EEC) where the decisions are only intergovernmental, not via pan-European bodies. 78% of the EFD MEP support the current EU trade and investment agreement negotiations with the US.

The Nationalists: This is the far right bloc led by Marine Le Pen of France’s Front National. In contrast with a focus on “national sovereignty” (which is mostly about decision-making power), they are focused on a perceived loss of “national identity” in their home countries, which is a much more dangerous sentiment. They are protectionist, they reject immigration, they purport to be ultra-patriots, and they particularly emphasize strong stances against Islam and multiculturalism. They are represented by the informal organization European Alliance for Freedom (EAF), which is composed of the FN, the Dutch PVV of Gert Wilders, the Swedish Democrats, and the FPÖ of Heinz-Christian Strache (Austria). Nationalists voted against free trade pacts, in contrast with the EFD.

Neo-Nazis and Fascists: Golden Dawn in Greece and Jobbik in Hungary have both openly claimed a neo-Nazi or fascist ideology. They organize paramilitary demonstrations, for example. In an effort to legitimize the slightly less racist nationalists, Marine Le Pen denied both parties the right to participate in the EAF.

Other Previously Fringe Populists: The NVA is Flemish conservative separatist movement in Belgium, which arrived first in both European and national general elections back home (bringing it out of the fringe, while not moderating it). In Italy, the M5S (comedian-turned-politician Beppe Grillo’s Five-Star Movement) has no clear ideology but they take every stance that looks popular. It is against euro and it is very ambiguous about immigration. They finished well behind the mainstream center-left, but they are increasingly a political force in Italian politics, despite very little coherence.

Unsurprisingly, the populists are very divided. Sovereigntists do not want to be affiliated with Nationalists, which they consider “not respectable.” The ideologies do differ somewhat, but primarily the former do not want to be considered racists – even if they may have very close stances to the latter on immigration or the European Union. Some of EFD’s parties participate in government coalitions in their home countries, so they have to be careful about their image. For example, the Danish People’s Party backed the liberal government of Anders Fogh Rasmussen from 2001 to 2011. Today, the Order and Justice Party is in a coalition government led by the social-democrats in Lithuania.

Fragmented right

Despite the overall surge of right-wing, anti-EU votes, that fragmentation poses a problem for those MEPs. It will be very difficult, for example, for Marine Le Pen to form an official parliamentary group with the required 25 MEPs from 7 different countries. Most of the FN’s allies or potential allies crashed in this European election. In Netherlands, the PVV lost 3.5%, and in Belgium, the Vlaams Belang got only 4.26% losing 5.56% and one of its two EU seats. In Bulgaria, Romania, and Slovakia, the far right literally plummeted and lost all its seats. The newly formed right-wing, nationalist “Alliance For Croatia” finished 4th in Croatia with 7% and failed to pick up a seat. The anti-NATO, anti-EU, ultra-nationalist Slovenians of the SNS improved their showing over 2009 but also failed to win a seat. The EAF is thus now composed of parties from only four countries: Austria, Belgium, France and Netherlands – three countries short of the threshold for official recognition.

Another consideration gives us reason to qualify the rise of the far right. While populists in general fared well, in only two countries (Denmark and France), did radical right-wing nationalist parties arrive on top.

The UKIP, which won the most EU seats from the United Kingdom, is certainly populist and euroskeptic, but it is a little bit more moderate about immigration and was not founded by ex-fascists in the way DPP or FN were. Its stances about immigration are closer to those of traditional conservatives. However, that does not exclude the UKIP from accusations of racism. Moreover, it seems likely that the UKIP performed as well as they did by absorbing the supporters of the less socially acceptable (i.e. borderline fascist) British National Party (BNP), which disappeared of the political scene by losing its 6% from the last election.

But elsewhere, the opposite happened, as euroskeptics lost vote share to the nationalists during this election compared to 2009. In Austria, two euroskeptic parties disappeared, The Austrian far-right increased by nearly 3 points but only 20.2% of Austrian vote went to euroskeptic parties, versus 34.96% in 2009.

Leftists and other anti-establishment winners

Additionally, we should also qualify the right’s surge by noting that the radical left made a sharp increase in Southern Europe and in Ireland. The EUL/NGL gained 10 seats. The Greek party Syriza, whose national leader Alexis Tsipras was the EUL/NGL’s candidate for the European Commission, arrived first in Greece. In Spain and in Portugal, the radical left also earned very good results, via new parties such as Spain’s “Podemos,” which ideologically aligns with parties like Syriza, or via older organizations like the Communist Party of Portugal. The far left collectively won as many seats as the Non-Attached members. Notably, in contrast with the right, leftists like Tsipras are not against euro or the EU as a concept; he only denounced the austerity policies advocated by the EU leaders in recent years.

If we subtract populists from the “Others” MEPs, 24 came from new parties that had not previously won seats or did not exist. There are stunt candidates such as DIE PARTEI in Germany — the party of the local version of Stephen Colbert — or the Party of Animals in Netherlands. There also pro-EU but pro-reform parties such as “The River” from Greece, which call for a renewal of the political scene.

The real reason to worry

To conclude, the 2014 European Parliament Election was marked by the growing questioning of the EU by the mostly right-wing populists and by the left for its austerity policy. The populists sharply increased their number of MEPs, which rocketed from 65 to 109. And despite their fragmentation, this European parliament will be the most euroskeptic of its history.

The low turnout, the bad results of ruling national parties, and the rise of populist parties and new parties are a sign of a deep crisis of confidence of citizens in their own institutions and governments as much as in the EU. In France and in Greece, the mistrust about government and traditional political forces is particularly strong.

However, the rise of the populist parties should not be interpreted as any unified explosion of the far right, which had very localized increases (France, Denmark, Austria, Greece, Sweden) for parties that will struggle to get along with each other, let alone the mainstream blocs that will still dominate the EU parliament.

Nevertheless, the current elites should be cautious about their next moves in light of the clear, broad-spectrum opposition to recent policies. Failure to recognize the warning of the 2014 election could spell deeper trouble — and even stronger successes for extreme populist parties — in the future.

Editor’s note: Etienne Borocco is a national counselor of the Union of Democrats and Independents, in France. This article was edited by Bill.