The popular retelling says that on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, the guns of August 1914 finally fell silent, ending “The War to End All Wars.” The popular follow-up joke is to point out that the Second World War, which began nearly twenty years later, proved that label false. Today the date remains a holiday in many of the Allied countries – including the United States, where it is now called Veterans Day.

In fact, not only did the war not really end on November 11th 1918, but the continuing fighting actually sprawled even further across the world. In many ways, it’s the wars “after the war” that really shaped what was to follow and the world we live in today, far more than almost any battle in World War One itself on the original fronts in Europe.

A shattering, rolling wave of secondary war, which began with the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia 369 days before the Western Front Armistice, triggered five “bonus” years of very heavy fighting that reformulated the modern world after the supposed cease-fire. These were waged in part by various revolutionary and counter-revolutionary local armies in a dozen countries, by anti-colonial forces against Western colonialists, and by the same Allied Powers that would continue to insist the war had ended in November 1918.

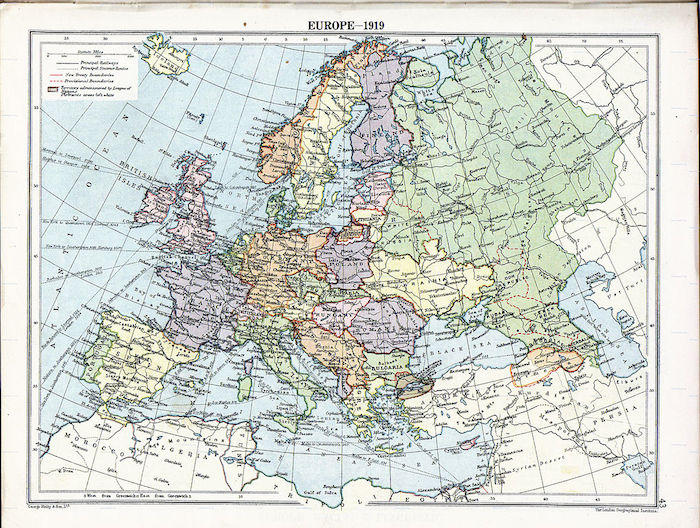

The famous Versailles Treaty was preceded and followed up by round after round of accompanying treaties frantically attempting to bridge the widening gap between the “ideal” boundaries envisioned by the victorious Allied Powers and the facts on the ground. One of these side treaties was so delusional it purported to divide Ottoman territory under Allied directive by agreement with the Ottoman sultan, who no longer had the effective power to sign any deals, and with the borders to be drawn by a nearly incapacitated Woodrow Wilson less than a year after his stroke. It was, of course, never implementable.

From the Russian Civil War … to the border battles of the former Russian imperial territories against each other … to the wars exploding across the former Ottoman Empire … to the far-flung European colonies around the world, World War One continued to grow, metastasize, and envelop country after country well beyond November 1918.

When it was all truly over, Europe had a half-dozen new states, a half-dozen others had already come and gone, the Middle East was carved up along the arbitrary lines of today’s conflicts, Turkey had declared independence from itself and the 16th century, a Communist government solidly held power in Russia and Ukraine after defeating the same military forces that had just broken the German Empire, Ireland had departed from Britain by force and civil war, several African and Pacific colonies had been arbitrarily reassigned to Western rulers speaking entirely different languages from the earlier colonizers, and existing colonies were laying the groundwork for mass resistance and violent separation.

Compared to the glacial, inch-by-inch pace of the four-year battle for control of highly strategic Belgian mud, the wars that followed often seemed to shift and create national borders faster than ocean tides.

In Russia and in the emergent Turkey, rapidly moving fronts demonstrated that everyone had suddenly remembered the cruel foolishness of fixed trench warfare and pointless sieges. British, American, and French “expeditions” invaded and occupy parts of the two countries, expecting to face the same incompetence seen from 1914-1918. Instead they discovered that a populist revolutionary people’s army fighting for its national survival and popular liberation will always outperform an unmotivated imperial army fighting incomprehensibly arcane monarchical wars for mystifying alliances.

Turkish military victories against the short-lived Republic of Armenia at the edge of the Caucasus – part of a massive tangle of wars there just from 1917 to 1922 – also paved the way for Russian re-occupation of its (alternately mutually federated and mutually despising) southern provinces and the creation of a “Union” of Soviet Republics ruled from Bolshevik Moscow. Turkey, reasonably satisfied with its own new borders and ethnic composition and having extracted recognition from the Allies, would declare itself into existence in 1923.

Suppressed and competing nationalisms in the once-partitioned countries of Poland and Ukraine — among others — re-emerged and promptly fell back on medieval claims and counter-claims to justify fighting each other for territory until the sweeping successes of the advancing Bolshevik Red Army in Russia rendered it largely moot until after the “next” war ended in 1945.

All over the world, national liberation movements, inspired by the Russian Bolshevik example or directly aided by the leadership in Moscow, would soon take on a distinctly communist flavor and set the tone for the coming global decades of strife between communist and anti-communist blocs.

In Europe itself, high hopes for transitions from medieval throwback monarchies to widespread popular democracy were quickly dashed in an Allied-approved fever to suppress the “wrong” kinds of self-determination and public participation, whether nationalistic or socialistic in character. Short of the Red-White-Black wars of eastern Europe and Russia, civil unrest in the streets quickly led to authoritarian repression of a new variety – nationalist, militarist, and right-wing – a combination that proved so massively deadly within a matter of years.

In Austria, a population stripped of its national symbols and leadership and barred by the Allied governments from joining their ethno-linguistic compatriots in a German super-state, cast about forlornly for a distinct identity. They fared far better than neighboring Hungary, their former partners in multi-national empire, which found itself suddenly under the rule of an iron-fisted admiral. His abrupt postwar lack of a coastline and navy inspired him to seize power – and a career change – as he opted to become a king-less Regent instead of a ship-less captain. On his watch, landlocked Hungary faced neither collectivization nor amphibious assault. Other eastern, central, and even western European countries quickly followed suit into right-wing military-backed coups.

Within four years of November 11, 1918 a wounded Italian Front veteran named Benito Mussolini had marched on Rome. Just days short of peak hyperinflation and of the fifth anniversary of Germany’s armistice with the Allied Powers, a wounded Western Front veteran named Adolf Hitler had tried to seize power in a Munich auditorium.

History is rarely as neat and clean as the school textbook elisions suggest. Instinctively, most of us know this, but it is still usually the broad-strokes renditions of history that inform current policy. The oversimplifications cast today’s complexities as both insurmountable (or never-before-seen) quagmires and Gordian Knots to be hacked through incautiously “like they did in the good old days.” Of course, in reality, many of the decisions undertaken in those decisive years were made in the face of similarly thorny chaos and often produced the very problems lingering today. Post-conflict resolution is never easy, but it is made harder by the illusions of a tidily partitioned (and fictional) history where peace fell universally one autumn day in 1918 and continued unbroken for nearly 238 straight months until the next world war.

All of the above is just the tip of the iceberg that was the seething and convulsing world at war from November 1918 to November 1923, the five-year span of conflict and social upheaval that immediately followed the Western Front Armistice. A lot happened in those 5 years. Perhaps more, in fact, than in the four and a half years demarcating World War One.

London Geographical Institute map of Europe in 1919 after the Treaty of Versailles. (Via Wikimedia)

Map of Europe in 1924 after the wars and treaties that followed World War I, from William Shepherd’s Historical Atlas (1923-26). (Via Emerson Kent and UT Austin)