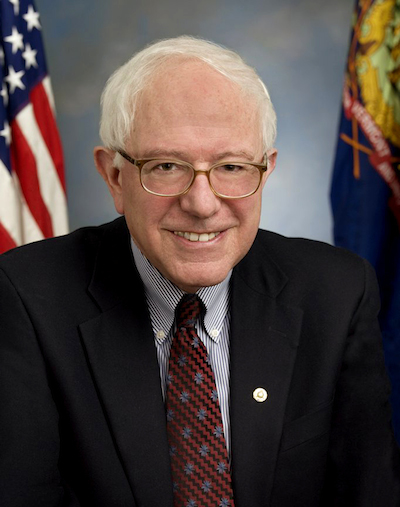

Normally I avoid posting stuff like this because it’s usually speculative nonsense, but apparently independent U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont has been seriously exploring a presidential campaign for the Democratic(!) nomination, to the point of visiting early states like Iowa and talking openly about his consideration of running.

Normally I avoid posting stuff like this because it’s usually speculative nonsense, but apparently independent U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont has been seriously exploring a presidential campaign for the Democratic(!) nomination, to the point of visiting early states like Iowa and talking openly about his consideration of running.

I have concerns about this idea, although I’m open to it and certainly would prefer a run within the party than a destructive independent challenge that siphons votes in the general election.

But regarding concerns: Namely, I don’t see this producing a serious internal debate in the party any more than two virtually identical establishment Dems, because it just means the establishment spends the whole campaign hippie-punching and laughing, without actually running much toward the left.

Sure, he — more than most lefties — might have the rhetorical juice to force tough questions on the trail, rather than being ignored entirely in the media and left out of debates. But I’m still not sure he would be taken seriously. Then again, John Edwards (subsequent personal revelations aside) ran one of the most “serious” populist/progressive campaigns in modern Democratic Party history, in 2008, without being laughed at, yet gained very little traction. Didn’t even win one state.

There’s also an equally important question/concern, beyond the electability and process, about whether governance would be well served by a Sanders win. If he magically had the ability to enact the policies he already supports, I’m sure we would benefit a lot and have much better governance. But we don’t live in a system where magic figures into it. Therefore, the winner is only effective when he or she is not an island and can build governing coalitions.

We’ve got to stop thinking about how to elect a spell-casting sorcerer and more about how to elect someone who can achieve results in the right direction once there. Thus, I wonder how much could really achieve with effectively very little legislative support base (since there’s no large social democratic bloc in Congress and even a centrist Democrat like President Obama had trouble consolidating agenda support under a Democratic majority).

However, in his defense, Sanders has also been relatively good at compromising effectively to make some gains (not just conceding everything to get something passed or refusing to concede anything and getting nothing.) Sanders notably slipped some interesting provisions into the Affordable Care Act regarding funding for rural health care clinics, for example, even if he wasn’t thrilled overall with the law’s approach to health reform.

He is, in that regard, very different from the ineffective foot-stomping wing of many louder members of Congress (from either party, but especially Dems) who talk a good game and then get nothing done. Others have started to copy Sanders’ approach with some success. He’s shown it’s possible to stand by one’s principles while compromising on the approach to making progress toward them.

Sanders is also notably a more strategic political thinker than many on the left. The fact he’s even looking at a run inside the Democratic Party, rather than outside of it, is a testament to that. But he’s probably most noted for having entered elected office as an independent after some early failed quixotic statewide runs, by studying where his biggest bases of support were in those campaigns and then concentrating on working his way up from there. So, first running in city politics in the community where he was most well regarded… then rising from Mayor to U.S. Representative… and ultimately to the U.S. Senate where he is now. By starting small and delivering results, he could show everyone he meant business, which was rewarded by re-election and elevation. All without compromising his principles to get there.

In sum, I think there’s no real reason to oppose him running for the Democratic nomination — though I wouldn’t be in favor of him running outside the party and splitting the vote — but it’s a very open question as to how effective he would be, both as a candidate or as a president (if he made it that far). And I have doubts it will achieve even the goal of bringing up important issues/questions inside the Democratic Party primary process. But that’s no reason not to try. If anyone can move the dial, it’s Bernie Sanders.

Normally I avoid posting

Normally I avoid posting