Warning: This post contains descriptions of extreme violence.

The situation in Central African Republic has descended into total chaos and horrific violence that firsthand observers are comparing to scenes from the Rwandan Genocide in 1994 (although — not that this is any consolation — the rate of killing is nowhere near as high).

Over a hundred people in the capital were killed or wounded in the last four days, according to the Red Cross.

Antoine Mbao Bogo, head of the CAR’s Red Cross, said that a total of 35 bodies had been recovered from the streets in many areas of the city over the last three days and eight more bodies had been found on Friday morning.

He said the victims were from both the Muslim and Christian communities.

“A few weeks ago people were dying more from gun wounds… but now it is mostly from things like knives. Sometimes they burn the corpses,” he told the BBC’s Focus on Africa radio programme.

Human Rights Watch is claiming that French troops stood by and did nothing as two Muslim men were hacked to death and mutilated at the entrance of the Christian refugee camp at the capital airport in Central African Republic. The French Defense Ministry has yet to comment. The French troops say their mandate is limited to disarming the Muslim militias and does not include intervening when the Christian militias begin attacking.

Technically, this may even be correct, given the comments by the French Defense Minister back in December:

French Defence Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian said the goal of the French military mission in the Central African Republic was to provide “a minimum of security to allow for a humanitarian intervention to be put in place”.

So, they are interpreting their mandate largely as a political security operation to pave the way for somebody else’s human security operation, which has yet to materialize. That’s not a particularly brave act. French peacekeeping troops, regardless of their orders, can and should act to protect civilians being killed in front of them — as a Dutch court ruled last year on their spineless peacekeepers in Bosnia in the 1995 Srebenica massacre. It’s a moral obligation to get involved when you’re an armed soldier seeing people commit murder in front of your very eyes.

Here’s another account also by Peter Bouckaert, director of emergencies for Human Rights Watch — one of the most vocal eyewitnesses offering news from the ground — published in The Independent:

Last Wednesday, immediately after the Séléka fled the Muslim neighbourhood of PK13 in Bangui, hundreds of anti-balaka fighters arrived, chasing away the remaining inhabitants, who fled to the relative safety of Rwandan peacekeepers at the scene. All around us, homes were being systematically looted and dismantled in an atmosphere of euphoric destruction. The main mosque was dismantled by a crowd of machete-wielding fighters who told us: “We do not want any more Muslims in our country. We will finish them all off. This country belongs to the Christians.”

I pleaded with the anti-balaka fighters to leave the PK13 residents alone, but they showed no sign of mercy, telling me: “You get them out of here, or they will all be dead by morning. We will take our revenge.”

The death records of the Bangui morgue read like a chapter from Dante’s Inferno: page after page of people tortured, lynched, shot, or burnt to death. The smell of rotting corpses is overwhelming, as when people die in such numbers, it is impossible to bury them immediately. On really bad days, no names are recorded, just the numbers of dead. In the 15 minutes we managed to remain amid the stench and horror, two more bodies arrived: a Muslim hacked to death with machetes, and a Christian shot dead by the Séléka.

The controversial “peacekeeping” troops from neighboring Chad continue to get into increasingly violent clashes with Christian militias and civilians as they evacuate their own citizens — and, unfortunately, the Séléka leaders who launched the waves of attacks in the first place.

In contrast, some of the other regional peacekeepers seem to be taking a more aggressive role in intervening between armed groups and unarmed civilian targets. For the Rwandan troops, who are by and large commanded by Tutsi officers who witnessed the 1994 anti-Tutsi genocide firsthand, this is deeply affecting.

A commander of the Rwandan troops told me that their intervention in the Central African Republic crisis is deeply personal for him and his troops: “What we see here reminds us of what we experienced in Rwanda in 1994,” he told me, “and we are absolutely determined not to let 1994 happen again.”

But they are utterly unprepared and under-equipped to cope with the scale of the unfolding violence. As in the Rwandan Genocide, it’s extremely hard for a small foreign peacekeeping force to stop autonomous, decentralized bands of machete-wielding irregulars and armed “civilians” who aren’t taking orders from anyone and have been whipped into a murderous frenzy.

Even the fresh UN troops from the EU probably won’t help as they’ve been tasked primarily with aiding the existing French protection details on the Christian camps in the capital. With the tables turned on the Muslim population, the Christians — while still at risk — aren’t the most vulnerable right now. The United Nations mission also remains in dire need of emergency funds.

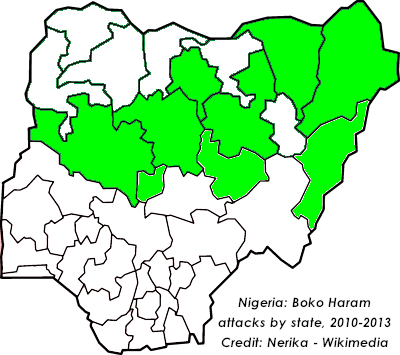

It also seems like an easy step down the path toward becoming completely mired in an unwinnable, transnational counterinsurgency operation in the Sahel —

It also seems like an easy step down the path toward becoming completely mired in an unwinnable, transnational counterinsurgency operation in the Sahel —

Central African Republic peacekeepers have

Central African Republic peacekeepers have