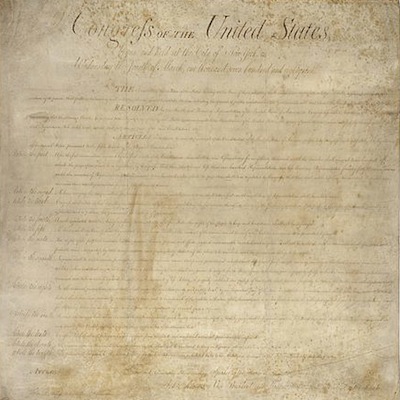

First an overview — here’s the full text of the 6th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (emphasis added to relevant sections for this post):

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

The U.S. Senate website handily provides a plain-English summary of the modern rights derived from this amendment. One of them is that:

Defendants in criminal cases are entitled to public trials that follow relatively soon after initiation of the charges.

This is intended to make sure that people aren’t jailed indefinitely without charges or a trial, as well as to minimize the risk of keeping innocent people in jail for years before a jury can get them freed.

The other key right to note is the right to have legal counsel help a defendant with his or her defense, a right which was extended to apply to state cases through the 14th Amendment (which imposes the U.S. Bill of Rights onto every state).

The Supreme Court first applied this latter part to state cases in a (possibly inadvertently) narrow ruling in Powell v. Alabama (1932), in which they found that in capital cases — ones where the death penalty was on the table — defendants must have access to their lawyers to plan a defense.

But defendants in non-capital cases were not really covered in that opinion, and low-income defendants in general were left to fend for themselves in obtaining counsel until a much later decision in Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), the subject of the film “Gideon’s Trumpet.” In that case, the court ruled that states had to provide (i.e. pay for) legal counsel for those who did not have their own lawyers, in order to fulfill the spirit of the 6th Amendment requirement, even if they weren’t actively denying access to counsel.

With everything that was going on earlier this year, I completely missed a horrid new Supreme Court ruling which functionally wipes out the public defender right found in Gideon v. Wainwright — as well as the right to a speedy trial. Granted, the public defender system wasn’t close to being a smoothly operating system to begin with, but the Supreme Court effectively announced there won’t be consequences for blatant violations, so it’s just up to the good will of the local governments to follow through.

In this case, a man in Louisiana was not given a trial for seven years, which is by no means a “speedy trial.” When he sued, the state admitted in the lower courts that the reason for the delay was on them and their failure to adequately fund and provide him legal representation. Later, during appeals, they tried to retract this admission and lay the fault on the defendant, saying he had repeatedly delayed the trial. Seven years is an awfully long time, and it’s hard to imagine a defendant trying to delay his own trial for that long — unless perhaps he understood that it was the only way to ensure he actually received some kind of representation.

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court said the State of Louisiana didn’t need to provide any compensation for the defendant for failure to provide a speedy trial and didn’t really punish it for failure to shore up its clearly inadequate public defender system.

And so it was that five justices decided this year that there don’t really need to be consequences for states who don’t execute the requirements laid forth in Gideon v. Wainwright. And that’s a problem — because the whole point of that decision was that failure to provide legal counsel to a defendant who doesn’t have his own, due to circumstance, translates in practical terms to failure to uphold his 6th Amendment right “to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.”

So now, after this ruling, what incentive do states have to maintain their public defender systems? Not much. Because there are also no consequences now for failing to provide a speedy trial, states can maintain the illusion of not denying access to counsel by just indefinitely postponing a trial.

The only likely consequence of that is the cost of imprisoning the defendants. But most states probably figure these people would go to prison anyway after their almost inevitable plea bargains, arranged by their hurried public defenders, and so that’s a wash. Plus, given the number of states heavily reliant on for-profit prisons and detention centers — who provide a lot of campaign cash to judges and legislators — there’s even less incentive to speed up the process.

I miss the old Supreme Court rulings when they still understood the difference between a literal interpretation of text and an interpretation that factors in functionality and real-world practice. Without a public defender, if you’re poor and can’t afford a lawyer, you don’t get “Assistance of Counsel.” That’s the real-world reason we have public defenders now in state cases.

Think of the moment on all those crime procedural shows when the low-income suspect (whether guilty or innocent) clams up during interrogation and asks for a lawyer. Earlier in the episode, of course, we probably saw the person get a warning (during their arrest) that they have the right to an attorney — and that if they cannot afford one, one will be appointed for them. So, on paper, we know and the character knows that they can ask for an attorney to be present during questioning. At that point, the detective character will usually say something about how the defendant should just answer the questions now to save the time and trouble of waiting for hours before the public defender shows up.

Because, off paper, this is how it really works. Nobody wants to sit around silently in an interrogation room for hours, so they start talking without their constitutionally-guaranteed counsel assisting them. Even if they’re actually innocent, they will probably say something that can (and will) be used against them in a court of law.

Now imagine that instead of it taking a few hours to see a lawyer, the public defender doesn’t show up to provide assistance until seven YEARS later. That’s not a 44 minute TV episode. This is the problem the country faces today. If you can’t afford your own lawyer, that’s just too bad for you, because it’s totally luck of the draw on whether and how fast you’ll ever see one.

The system needs to work better than this, and there ought to be consequences for states for being so lax about upholding their end of the deal that it doesn’t do the job it was created to do. But the Supreme Court doesn’t see it that way. As long as you eventually get a lawyer, even years later, a majority of the Supreme Court feels that your right to counsel has been met. And don’t even ask about a speedy trial. If you had wanted that, you should have waived your right to counsel and pled guilty.