Burkina Faso’s former longtime dictator Blaise Compaoré, still in exile since his October 2014 ouster, now faces an international arrest warrant for his role in the bloody 1987 coup that brought him to power against his once-friend Captain Thomas Sankara. The body believed to be that of Sankara, while still not positively identified, is “riddled with bullets” according to an autopsy released in October 2015.

Tag Archives: Blaise Compaoré

Violent clashes in Burundi as the president clings to power

After Burundi’s President Pierre Nkurunziza announced his long-anticipated plans to seek a third term as president in violation of the post-civil war constitution’s term limits, deadly protests erupted this weekend. They have escalated rapidly after initial fatalities:

Gunfire was heard and streets were barricaded in parts of the capital, Bujumbura, in the third day of protests, witnesses told the BBC. Police are blocking about students in the second city, Gitega, from joining the demonstrations, residents said.

The protests are the biggest in Burundi since the civil war ended in 2005. The army and police have been deployed to quell the protests, which have been described by government officials as an insurrection.

[…]

BBC Burundi analyst Prime Ndikumagenge says the phone lines of private radio stations have been cut, a decision apparently taken by the authorities to prevent news of protests from spreading.

This may be the contagion some observers speculated might unfold after the uprising in Burkina Faso last October, when President Blaise Compaoré tried to extend his presidency in a similar fashion.

Flag of Burundi

Burundi’s Army has been accused repeatedly of conducting extrajudicial mass executions of “rebels” and political opponents. Already, thousands of people have fled political persecution to neighboring countries in just a matter of months. Burundi also has a very low median age — half the population is younger than 17, according to the CIA World Factbook — and the President has essentially created child death squads by arming teenage members of his political party’s “youth wing.”

Burundi, which has the same colonially-fostered Hutu/Tutsi split as neighboring Rwanda, experienced a 12-year civil war beginning shortly before the Rwandan Genocide and continuing until 2005, despite repeated attempts to share power. The presidents of both countries were killed in a surface-to-air missile strike on their plane in 1994, in the incident which was widely seen as the trigger signal to initiate the genocide in Rwanda. However, the war in Burundi was already in progress at that point. Hundreds of thousands died before the 2005 peace deal.

It is interesting, however, to note that so far the armed forces have continued to respond to orders from President Nkurunziza. He is Hutu, and the armed forces are a mix of ex-rebel Hutus and the Tutsi regular troops from before the peace deal. In South Sudan, a merger of various ex-rebels from competing ethnic groups, which had been secured around the same time as the Burundi deal, basically broke down completely in December 2013 as certain factions obeyed the president and others the former vice-president, who had been sacked.

Diplomat Michel Kafando named interim Burkina Faso president

Michel Kafando, a longtime high-level Burkinabé diplomat, has been picked as the “consensus” interim president of Burkina Faso by the selection committee. The 72-year-old will fill the role of Acting President, appointing a prime minister to lead a 25-member cabinet, until the regularly scheduled November 2015 elections are held. He is expected to take office Friday, November 21, exactly three weeks after President Compaoré’s resignation.

From the France24 news report:

“The committee has just designated me to guide temporarily the destiny of our country. This is more than an honour. It’s a true mission which I will take with the utmost seriousness,” Kafando told journalists after his appointment.

Kafando served as the country’s ambassador to the United Nations from 1998 to 2011. Previously he was Burkina Faso’s foreign affairs minister […]

A committee of 23 officials chose him over other top candidates […] His candidacy was proposed by the army.

I’m a little troubled that the Army’s nominee — who was also a 13-year Compaoré appointee as UN ambassador — was chosen as interim president by the selection committee.

Additionally, a French-language news report by Burkina24 suggested that the entire “short list” of five names had been submitted to the selection committee by the military, contrary to Sunday’s reports that a number of interest groups would be submitting candidates. Perhaps the military narrowed that list down to something more manageable, but it would constitute interference all the same. According to the Burkina24 report, the religious and traditional groups did not make any nominations (indeed the Roman Catholic Church repudiated the nomination of Archbishop Paul Ouédraogo to the short list).

Of the remaining three, the selection committee also passed over two news media publishers and a widely-mentioned frontrunner, Joséphine Ouédraogo, a cabinet minister in the revolutionary Sankara government of 1983-1987. The latter was the final runner-up against Kafando, according to Burkina24.

Former Ambassador Kafando has the unusual credential of being a high-ranking appointee under at least three governments, theoretically at odds with each other. In 1981 and 1982, he served as Upper Volta’s Ambassador to the United Nations (pre-name change), as an appointee of the Colonel Zerbo military government of 1980-1982. (Zerbo, in addition to various criminal actions and anti-leftist policies, supposedly later became a Compaoré adviser following the latter’s 1987 coup that displaced the leftist Sankara government, which initially was very anti-Zerbo.) From September 1982 to August 1983, and as the only continuing member from the previous administration, Kafando served as Foreign Minister in the short-lived military government of Major Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo that had overthrown Zerbo. That government was overthrown in turn by Captain Sankara in August 1983. Kafando then appears to have left government for over a decade, spending at least part of the late 1980s in France obtaining his PhD at Paris-Sorbonne University, before returning to the UN posting in 1998 under Compaoré.

Perhaps this eclectic resume of administrations served under actually demonstrates an ability to work easily with a range of competing factions. Certainly, he is relatively well known by the international community due to these diplomatic postings (including to the UN Security Council), which is probably a plus for an impoverished country reliant on foreign assistance and involved in various security agreements.

Burkina Faso Army preps to hand back control to civilians

In continuing the rapid implementation of the ECOWAS-sponsored transition plan, the military government in Burkina Faso (which took power just 15 days ago) today gave civilian groups a one day deadline to narrow down their proposed interim leaders to a consensus choice, who will govern until November 2015 elections. Here are some key highlights from the BBC report:

Burkina Faso’s military ruler has told activist groups they have until Sunday afternoon to provide a list of candidates for interim national leader.

Lt Col Isaac Zida agreed [to] a transition plan with civilian political groups on Thursday, but no leader was named. The groups have agreed to submit a list of candidates to a 23-member council, which will then select a single leader.

In a communique on Saturday, Col Zida said civilian groups had until noon on Sunday to provide a list of candidates to serve as interim president. He also said the constitution was back in force in order to “allow the start of the establishment of a civilian transition”.

Under the charter agreed on Thursday, the interim president will be chosen by a special college composed of religious, military, political, civil and traditional leaders.

Let’s take another look at that constitutional power vacuum situation that led to the temporary — and thankfully apparently short-lived — military takeover after President Compaoré‘s resignation. Since many Western media sources were being a bit lazy about reporting the details accurately, I spent a number of hours immediately following the coup carefully parsing the constitution along with 2012, 2013, and early 2014 news articles from the country. My conclusion: Due to an ongoing political dispute well before the current crisis, Burkina Faso doesn’t actually have a Senate set up to fill the role of Senate President, even thought that position is designated without alternative in the 2012 Constitution as the Acting President if the Faso presidency becomes vacant.

In other words, there was no way any transition would have been constitutional, even if the Army had not suspended the constitution and assumed control. So, the “restoration” of the constitution today by the military doesn’t really fix that fundamental, unavoidable problem that led to their takeover in the first place.

However, here’s some good news: The uncreated Senate was supposed to have been composed of indirectly-elected representatives of the local municipalities (etc), worker groups, industry groups, religious groups, and (some) customary/traditional authorities (I think most were disbanded in the 1980s by Sankara). Thus, the plan announced Saturday essentially “restores” the Constitution to the extent actually possible and seems to try to emulate its spirit as closely as possible to fill the remaining gaps where it’s simply not feasible to follow the letter. For example, the acting civilian president will be chosen — by a 23 member council of representatives from the aforementioned interest groups — from a list submitted by those same groups and the 40 odd political parties in the country (or a lot of them anyway). That’s basically as close as humanly possibly to a duly-composed (in spirit) pseudo-Senate choosing a leader to fill the role of Acting President in lieu of a Senate President who never existed. Moreover, the military government has not attempted to rewrite, amend, or promulgate a new constitution.

If this plan holds up, this may prove to be one of the most efficient and minimally invasive military interventions in the democratic system of a country in recent memory. The real test, of course, will continue through the transitional civilian leadership period and into new elections (and presumably a less arcane and broken constitution eventually). But this is still a huge step, and a lesson to other would-be military interventionists both in Burkina Faso and abroad.

Burkina Faso’s Printemps Noir: A Black Spring or a fizzle?

When protesters in Burkina Faso’s capital last Thursday burned the parliament to the ground and forced President Compaoré’s resignation the following day, some there and in other sub-Saharan African nations immediately dubbed the uprising the “Black Spring,” in comparison to the ethnically-labeled Arab Spring of North Africa and the Middle East. They were hoping that Black Africans would have their own moment to try to throw out dictators in a big wave.

Francophone (French-speaking) Twitter was flooded with the phrase “printemps noir” — literally “Black Springtime” — used alongside and in comparison to “printemps arabe,” the French term for the Arab Spring uprising that kicked off in Tunisia in December 2010. Tunisia, like Burkina Faso, was formerly part of the French colonial system, and Tunisian dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali rose to power in November 1987 just weeks after Blaise Compaoré seized power in Burkina Faso, so the comparisons are natural.

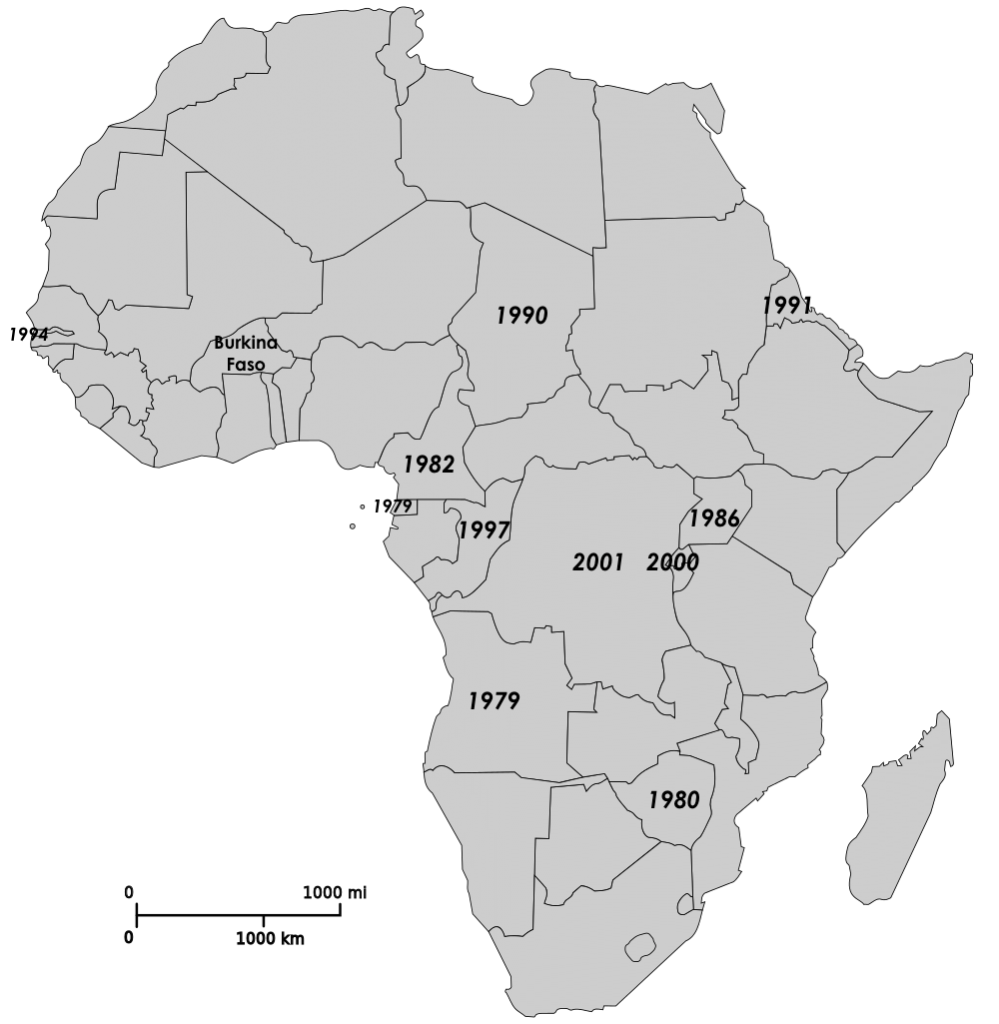

Moreover, there are a number of other sub-Saharan African leaders (see map at bottom) who have been in office either nearly as long or significantly longer, who might be vulnerable to a domino effect like that seen in North Africa, while others with authoritarian leanings from the post-Cold War period who might be looking to extend their rule unconstitutionally or excessively. In the latter category, Rwanda, DR Congo, Republic of Congo, Chad, etc. In the former, Cameroon’s Paul Biya has been president since 1982 (and remains entrenched despite recent mounting spillover chaos from the Nigeria insurrection); in Equatorial Guinea, one of Africa’s two “1979 Presidents” (now the world’s longest-serving non-monarch leaders) has passed the 35 year mark and shows no sign of stopping; Uganda; Zimbabwe; etc.

In sum, Reuters reports:

[…] several “Big Men” rulers are approaching the end of their mandates amid concerns that they may try to cling to power by changing their countries’ laws.

Particularly in West Africa, some opposition supporters believe they can thwart such ambitions in the same way that Arabs in North Africa forced out the rulers of countries such as Tunisia and Egypt in 2011.

But how likely is that really? For one thing, it’s still not clear yet that Burkina Faso will successfully move from a military-led “transition” government currently in power toward democratic, civilian rule.

For another, it’s distinctly possible that this is an outlier that won’t be replicated domino-style, as in North Africa and the Middle East. On the one hand, Burkina Faso isn’t all that similar to other countries that might appear to be primed for mass uprisings:

The poor, cotton-producing state south of the Sahara desert already had a tradition of street protest and military-supported social uprisings. Marxist military captain Thomas Sankara led a popular revolution in 1983 inspired by Fidel Castro’s rise to power in Cuba in the late 1950s.

[…]

However, they face more firmly entrenched rulers and elites than did the protesters in Burkina Faso. Crucial to the success of Compaore’s overthrow was army sympathy with the disgruntled masses, following a 2011 military revolt over unpaid bonuses.

[…]

By contrast, presidents of wealthy oil-producing states, such as Angola’s Jose Eduardo dos Santos or Equatorial Guinea’s Teodoro Obiang Nguema [both 35 years in power], can use state resources to grease the wheels of political patronage and invest in the loyalty of their military hierarchies.

Plus, they have the added advantage of seeing this coming from farther off, in part by having watched the missteps and failed suppression of the Arab Spring uprisings in some countries — as well as the far more “successful” suppression or avoidance tactics employed by some of the rulers of potential Arab Spring countries, such as the Kingdoms of Morocco and Jordan.

On the other hand, sometimes these things have a habit of getting away from you and beating expectations:

But veteran leaders cannot underestimate their increasingly vocal young urban populations. Millions of youngsters are coming onto the labour market and if their hunger for jobs, equality and a greater political say is not met, this could be a demographic time bomb for those who are reluctant to go.

After all, most observers (me included, to be sure) didn’t expect the Tunisian revolution’s example to explode so quickly and strongly into Libya, Egypt, or Yemen — and result in the collapse of their strongmen.

Burkina Faso: Attempted 3rd coup in 3 days fails; protesters cleared

On Sunday, Burkina Faso’s capital again filled with thousands of protesters, this time demonstrating against the new “transitional” government of Col. Zida, whose backers unexpectedly seized power from within the military on early Saturday, removing the first military government set up on Friday after Blaise Compaoré resigned the presidency.

Zida, who was Army Spokesman and commander of the presidential guard, is less well known than many of the country’s top officers and is feared to be even more tied to the old order than the Friday government. Although he pledged a quick transition to elections and a new constitution, the timeline was undefined. One protester told Reuters why there was enough concern today to take to the streets again today:

“They are coming from Kossyam to enslave us,” said protestor Sanou Eric, in a reference to the Presidential Palace. “This is a coup d’etat. Zida has come out of nowhere.”

Zida’s Saturday government was created in the country’s seventh successful military coup since independence from France in 1960.

Later in the day today an apparent attempted 3rd coup in as many days was thwarted, according to Reuters reporting in the capital:

Witnesses said prominent opposition leader Saran Sereme and an army general, along with a crowd of their supporters, headed to the RTB Television on Sunday afternoon to declare themselves in charge of the transition but were thwarted by the army.

Gunshots rang out at the station and the channel was taken off the air. There were no reports of anybody being injured.

The Army reportedly dispersed the massing protesters in the capital streets with live-fire warning shots.

The international community continues to play wait-and-see, in light of the fact that they cannot automatically label the situation a coup (with all the legal implications that brings) because the constitutionally prescribed transfer of power was impossible due to the specified successor position not existing when the presidency became vacant on Friday after 27 uninterrupted years of control.

In other news, witnesses in neighboring Côte D’Ivoire reported the arrival of former President Compaoré in their capital on Saturday, according to the AFP:

…Burkina Faso’s deposed president reportedly arrived in neighbouring Ivory Coast, less than 24 hours after being forced from power. Compaore, who resigned on Friday amid mass protests against his 27-year rule, arrived in the capital Yamoussoukro on Saturday with his family.

“The services of the President hotel in Yamoussoukro served him [Compaore] dinner yesterday [Friday] and breakfast this morning [Saturday],” a hotel employee told the AFP news agency. A local resident told the AFP he saw “a long cortege of around 30 cars going in the direction of the villa,” which is used as a semi-official residence for foreign dignitaries.

Possible coup inside Burkina Faso military government

On Friday, Burkina Faso’s President Blaise Compaoré resigned from office after 27 years in power and a week of escalating protests (see our background report). In light of a constitutional vacuum, he handed power to General Honore Traoré, head of the Burkinabé Army, his former aide-de-camp, and called for elections within 90 days. Traoré made no comment on the latter point.

While protesters celebrated the fall of Compaoré, whose whereabouts are now unknown, General Traoré is still generally regarded as being too personally close to the former president.

Already things are looking very shaky for the transitional military government under Traoré:

The presidential guard’s second in command [and the Army Spokesman], Colonel Isaac Zida, says he has assumed power as head of state.

[…]

Col Zida said General Honore Traore’s claim to be head of state was now “obsolete”.

“I now assume… the responsibilities of head of the transition and of head of state to assure the continuation of the state” and a “smooth democratic transition”, said Col Zida in a televised speech quoted by AFP news agency.

Reuters reported that Col Zida, in a statement read out on local radio, had said: “I assume the functions of head of state and I call on (West African regional bloc) Ecowas and the international community to demonstrate their understanding and support the new authorities.”

From independence in 1960 to the end of the Cold War, there were at least five successful coup d’états and then none until now. Friday’s military takeover as a “transitional” government in the absence of a viable constitutional successor makes six, and if this one succeeds that will probably qualify as the seventh, despite being internal to the military and in such rapid succession.

Added: Reuters is counting this as number seven and reports:

“I assume from today the responsibilities of head of this transition and head of state,” Zida said, dressed in military fatigues, in the studio of BF1 television.

“I salute the memory of the martyrs of this uprising and bow to the sacrifices made by our people.”

[…]

Zida said the army had stepped in to avoid anarchy and ensure a swift democratic transition. He said a roadmap to elections would be drafted by a body drawn from different elements of society, including political parties and civil society.

[…]

“This is not a coup d’etat but a popular uprising,” he told Reuters after making the statement. “The people have hopes and expectations, and we believe we have understood them.”