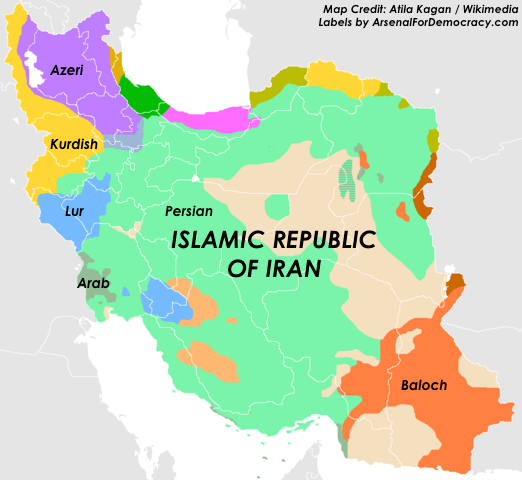

Modern Iran traces its roots to ancient Persia and Persians remain a majority in the country. However, the country is home to many languages and ethnicities. Indeed, the share of non-Persians among Iran’s population, which totals 82 million people, is at least 39%, according to The World Factbook. Given that ethnicity can be a fluid concept, Iran’s non-Persian population might actually be closer to 50%. One indication is that only 53% of Iranians speak Persian. There are at least seven other languages spoken by a significant number of citizens.

All that being said, although Iran is thus a country of astounding ethnic, cultural, and linguistic diversity, Persians continue to dominate the country’s central government.

This brief report, produced by Arsenal For Democracy and The Globalist Research Center, covers three major ethnic minorities in western Iran today, examining their modern history and how their presence has affected post-Revolution relations between Iran and its neighbors. (Major western Iran minority ethno-linguistic groups not covered: Lurs, Gilaks, Mazanderanis.)

Map of selected ethno-linguistic minorities of Iran. (More info at Wikimedia)

Arab Iranians

Arabs are a small ethnic minority in Iran. They account for only about 2% of Iran’s population. Some 1.5 million Arabs live along the Iraqi border in southwest Iran. Arabs have lived there since the Islamic conquest of Iran 12 centuries ago.

Much of the Arab-dominated border area is within the country’s oil-rich Khuzestan Province, the center of the brutal Iran-Iraq War. Saddam Hussein invaded and occupied it in 1980. He did so, mistakenly believing Arab-Iranians would rally to him after protests and riots there during the 1979 revolution. Instead, they fled the area until the new Iranian revolutionary military could regroup and counterattack by 1982.

Khuzestan remains poor and was never fully rebuilt after the war. Deadly clashes between Arab-Iranians and security forces break out on a regular basis, including several in 2015. Separatists also sometimes stage terrorist attacks.

Kurdish Iranians

Iran’s four million Kurds predominantly populate a mountainous northwestern region of the country. Accounting for about 10% of Iran’s population, they have long harbored separatist tendencies.

In 1946, the Soviet Union tried to establish puppet buffer states in northwest Iran, including a Kurdish state. It had occupied the area in 1941 to block Germany from capturing Iran’s oilfields. However, unlike in the case of Eastern Europe, this early Cold War partition proved short-lived, after the Red Army decided to withdraw, pursuant to the UN Security Council’s second and third resolutions ever.

There are also separatist Kurds in Iraq, Turkey, and Syria. In Iraq, some six million Kurds comprise roughly 15-20% of the population. In Turkey, 14.3 million Kurds make up 18% of the population. In war-torn Syria, the Kurdish population is probably between one and two million and accounts for a much smaller share. Syria’s government has sometimes supported Kurdish militants as a counterweight against enemies or rivals, including Turkey. The four major Kurdish populations, totaling at least 25 million people, live largely contiguous to each other across national borders. While this proximity sometimes encourages cooperation between separatist groups, they have also often been rivals for influence within the Kurdish nationalist movement.

The leaders of Iran’s Islamic Revolution of 1979 viewed Kurdish ethnic separatism as a serious threat to their ideology of unity through religion. Kurdish separatists, who had helped overthrow the Shah earlier that year, saw the revolution as the moment for independence and began seizing control of their communities. However, Iran’s revolutionary armed forces focused on crushing this major Kurdish rebellion as early as 1980, even in the face of Saddam Hussein’s invasion into the Khuzestan province. Violence between the state and Kurdish separatists continues intermittently, 36 years later. The Kurds’ integration into Iranian society has also been limited.

Azeri Iranians

Iran is also home to at least 12 million Azeris, a Turkic-descended ethnicity comprising 16% of the country’s total population. They mainly live in the Iran’s northwest border provinces, next to the former Soviet republic Azerbaijan. That country has nearly nine million ethnic Azeris among its citizens, who account for about 92% of its 9.8 million people.

While concentrated in the northwest, Azeris live throughout Iran in conditions closely resembling those of the Persian majority. Despite sporadic problems, Azeris are comfortably integrated into Iranian society and hold positions of power in the government and military.

The revolutionary government, while opposed to Azeri nationalist activity in Iran, has defended Azeri-Iranians from persecution, in contrast with its own actions against Arabs or Kurds. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in 2006 said, “Azeris have always bravely defended the Islamic revolution and the sovereignty of this country.”

Ethnic Azeris have been divided between Iran and Azerbaijan (formerly part of Russia and then the USSR) since 1828, when Iran was pushed out of the Caucusus by a peace treaty with the growing Russian Empire.

Both Iran and Azerbaijan are Shia-majority Muslim nations, of which there are only four in the world; the others are Iraq and Bahrain. However, Azerbaijan is largely secular in practice, in contrast with the public religiosity of Iran’s Islamic Republic.

During the post-Soviet war between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region in the early 1990s, Iran economically aided Armenia after Azerbaijan’s president suggested a desire to unify “Greater Azerbaijan.” This threatened Iranian sovereignty, since a majority of all Azeris live in Iran.

Iran’s regional rivals Turkey and Israel also formed lasting military and economic ties with Azerbaijan during the war.

Despite some continued bilateral tension, an unofficial strategic understanding has been reached: Iran will not try to spread Islamic Revolution to Azerbaijan, while Azerbaijan will not foster ethnic separatism inside Iran. Neither country’s Azeri population seems to be interested in pursuing such an option anyway.