Ah, Cinco de Mayo. The annual day where snooty Americans get to tell other Americans (who are really just trying to drink in peace while wearing face paint in the Mexican national colors) that “actually” Cinco de Mayo “isn’t a real Mexican holiday” and “has no importance or significance” — and then even snootier Americans (like me!) get to tell the first group that the Second French Empire’s defeat in the Battle of Puebla was strategically important to the preservation of the Union during the U.S. Civil War, by preventing Napoleon III from invading to help the Confederacy.

Ah, Cinco de Mayo. The annual day where snooty Americans get to tell other Americans (who are really just trying to drink in peace while wearing face paint in the Mexican national colors) that “actually” Cinco de Mayo “isn’t a real Mexican holiday” and “has no importance or significance” — and then even snootier Americans (like me!) get to tell the first group that the Second French Empire’s defeat in the Battle of Puebla was strategically important to the preservation of the Union during the U.S. Civil War, by preventing Napoleon III from invading to help the Confederacy.

To this day, even though the holiday is not widely celebrated in Mexico (because it was not very important within Mexico as a whole in the long run, since the French won the war anyway at least briefly), it’s important to acknowledge what makes it so unusual in the United States:

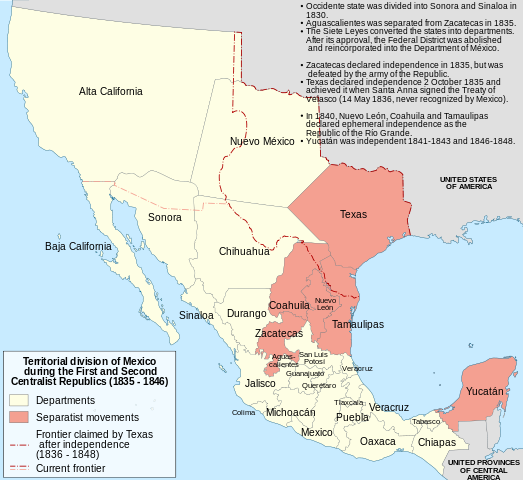

1) It’s a rare day where Mexican culture and heritage is openly celebrated in a country that includes the territory that used to be of about half of Mexico. These areas make up parts or all of ten U.S. states now. And the country at large is home to millions of people of Mexican descent. They deserve more than a day. Don’t take this one away!

2) The holiday’s U.S. roots began in the State of California when news of the 1862 victory in Puebla, Mexico reached the Mexican miners in California. Both the United States and Mexico were being torn apart by war at the time. The anniversary of the battle has been celebrated every year since 1863 in California. (1863!) When people say “it’s not a real Mexican holiday,” that minimizes the fact that it’s essentially always been a celebration of Californian Mexican-Americans.

Thus, it’s a great way to celebrate Mexico’s culture and close historical ties to the United States — something that has tragically been forgotten amid the push for bigger border fences and a rising tide of anti-Mexican xenophobia.

And even though Puebla is a southern Mexican state, it is a convenient reason to celebrate the cross-border regional culture of northern Mexico and Alta California/Nuevo Mexico, or the U.S. Southwest.

Mexico has long had many of the same sectional differences that plague(d) the United States. The gross Anglo-American Slaveholders Revolt in Tejas that led to the creation of an independent Texas is a dark mark. But beyond them, a lot of actual (non-U.S.) northern Mexicans wanted out from the rest of the country. Most got it, via the Mexican Cession (though that probably wasn’t what most residents had in mind), but a few states were left behind. They remained close with the United States — often more so than with central Mexico. Until big migration restrictions were put into place, there was a lot of economic activity back and forth in both directions between the American Southwest and northern Mexico, even well into the twentieth century.

U.S. history has long been closely intertwined with Mexican history, both for good and ill. It’s pretty great that a century and a half later, a lot of Americans (including non-Mexicans) take at least one day to acknowledge (however casually, in some cases) that almost a third of the U.S. mainland by area used to be half of another country and that Mexican-Americans still part of both our history and present.

And if nothing else, I just want to reiterate that the “insignificant” battle kept the French intervention force distracted in Mexico long enough for the U.S. Army to regain the momentum and win the Civil War before the Confederates could persuade any European governments to help them.

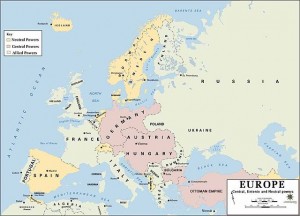

The Crimea annexation has raised a crucial question: What is the world to do when a country with a large military and nuclear weapons decides to end a (voluntary, it turns out) period of non-aggression toward its neighbors?

The Crimea annexation has raised a crucial question: What is the world to do when a country with a large military and nuclear weapons decides to end a (voluntary, it turns out) period of non-aggression toward its neighbors?

If nothing else, let’s all stop for a moment to appreciate that the joint Russian-US space program efforts have continued totally uninterrupted, despite everything happening politically, including a barrage of American sanctions on senior Russian officials.

If nothing else, let’s all stop for a moment to appreciate that the joint Russian-US space program efforts have continued totally uninterrupted, despite everything happening politically, including a barrage of American sanctions on senior Russian officials.