Arsenal For Democracy estimates and maps the perimeter dimensions of Turkey’s potential occupation zone / U.S. no-fly zone in northern Syria. (The detail map is near the middle, after the evidence used to prepare it. A regional map showing the area in context is attached at the end.)

As I’ve explored previously, for the past month, the Turkish military and the Turkish government have been disagreeing quasi-publicly as to whether to invade and occupy northern Syria to establish a “humanitarian zone” (supposedly for refugees).

The military brass is trying to delay at least until a new government is formed and the newly-elected parliament can take a vote on it, while the ruling AK Party is pushing for an intervention sooner. It seems to have been an AK Party aspiration, off and on, since at least September 2014, whereas the military isn’t entirely sure it’s a good idea in a general.

On February 22, 2015, Turkey’s military staged a lightning incursion in and out Syria, moving more than 600 troops and 100 tanks along the Euphrates River for some 22 miles (35 km) and then returning to the Turkish border a few hours later. The objective then was ostensibly to secure and re-locate a historic tomb of national significance (which was being guarded by Turkish Special Forces in a vulnerable position). But it may have also served to test Turkey’s ability to invade that far into Syria’s warzones without major resistance, although it was on the other side of the river, south of Kobani.

Of course, a speedy raid and departure would be quite different from a full-scale intervention to hold territory indefinitely. So how big of an area are we actually talking about for this possible massive military operation?

Soner Cagaptay, the director of the Turkish Research Program at The Washington Institute, indicated in The Globalist in early July (based on “media reports”) that the zone would be as follows:

Specifically, Turkish forces may be aiming to seize a [88-km] 55-mile-long stretch of territory from Azaz in the west to Jarabulus in the east, thus establishing a [32-km] 20-mile-deep cordon sanitaire against the violence next door and creating a staging ground for pro-Turkey Syrian rebels.

Following meetings between U.S. and Turkish government officials this week, Turkey’s Hurriyet Daily News reported the latest rumors, which were far more expansive:

A recent joint action consensus between Turkey and the United States, which includes the use of the İncirlik Airbase in southern Turkey in fight against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) jihadists, also covers a partial no-fly zone over the Turkey-Syria border, according to sources.

The 90-kilometer line between Syria’s Mare [Marea] and Cerablus [Jarabulus] will be 40 to 50 kilometers deep, sources told daily Hürriyet, while elaborating on the consensus outlined by Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç, following a cabinet meeting on July 22.

However, sources avoided saying whether such a zone would be broadened in the future.

In addition to that representing a larger area, this news also suggests Turkey’s longstanding demand of getting U.S. air support and a no-fly zone for such an operation may have been met.

If it comes to pass with those enlarged specifications, as depicted in the map below, the U.S.-patrolled no-fly zone and Turkish-occupied “humanitarian zone” on the ground in Syria is going to run to the edge of the city of Aleppo at minimum — and could theoretically even include the entire city (not depicted). That variance represents the aforementioned range of a 40-50 km depth from the border, which falls either on the north side of the city (leaving it out) or the south side (including it).

However, it seems unlikely to me that an initial zone would include Aleppo itself, simply because it has been the site of a protracted siege for several years and Turkey would have to break into it to take it over, while the U.S. would have to fight for air supremacy over the city. Of course, some hardline nationalists in Turkey have never gotten over the loss of Aleppo to the French and Syrians in the border-setting wars that followed the Ottoman Empire’s destruction in World War I.

Regardless of motivations, even stopping just short of Aleppo would put the Turkish military into position to provide direct military support to its allied opposition forces trapped in Aleppo. The Syrian Army would likely have to withdraw, and the Syrian Air Force might not be able to continue aerial attacks.

Below is my approximated projection of the minimum Turkish Occupation Zone based on various recent Turkish media descriptions, as well as (loosely upon) local highways and land features. In terms of west-east width, this is using the wider “Azaz in the west to Jarabulus in the east” parameter than the one reported in Hurriyet (Marea to Jarabulus). In terms of depth, it is using the much larger 40-50 km measurement from Hurriyet, at least on the southwest corner, where it seems most applicable.

July 24, 2015 projection of the perimeter of a potential Turkish occupation zone and no-fly zone in northern Syria. Click to enlarge.

First, a key observation: Manbij is located on the M4 highway. If Manbij is indeed the big southeast anchor point of the occupation zone, as even the conservative estimate would suggest, that highway not only forms a convenient southern perimeter line but also restricts ISIS movements westward from Raqqa. Moreover, it is the same road that extends to the Euphrates, to the precise spot where the Tomb of Suleyman Shah was located until it was moved in the February operation. So that might be another sign that the incursion was a test.

Second: That’s a pretty huge area, currently controlled (to my knowledge) almost entirely by ISIS and the Syrian Army, except for some of the western locations, which are held by Saudi-backed rebel groups that are theoretically also aligned with Turkey. They might, however, not be overly receptive to a Turkish military occupation in a predominantly Arab territory (though ethnic facts on the ground didn’t deter Turkey’s “peacekeeping” occupation of northern Cyprus in 1974, which hasn’t ended 41 years later). On either side of the Syrian zone are Syrian Kurdish forces and communities (including Kobani, across the Euphrates on the eastern side).

Third: The U.S. no-fly zone would reportedly be based out of Incirlik Air Base in Turkey (see our map) if that deal doesn’t fall apart again.

Fourth, a qualification, as I was taught to make at the University of Delaware Geography Department: keep in mind that I am looking at satellite and road maps with a somewhat limited familiarity with the area in question. Military conditions and physical features on the ground that I can’t see might make some of the lines way off.

[Added at 4:45 AM EDT: While I was writing this report, the wires broke the news that Turkish fighter jets began airstrikes across the border from the Turkish town of Kilis on ISIS targets inside Syria. You can see Kilis is directly north of the northwest corner of the zone mapped above, which means the targets are probably inside the zone. Turkey says the jets fired from within Turkish airspace.]

[Added at 6:25 PM EDT: The Turkish Foreign Ministry has confirmed that U.S. Air Force planes and other coalition partners will be permitted to fly armed and manned missions from Incirlik Air Base and bases at Diyarbakir and elsewhere. The Ministry did not confirm whether a no-fly zone was part of the deal.]

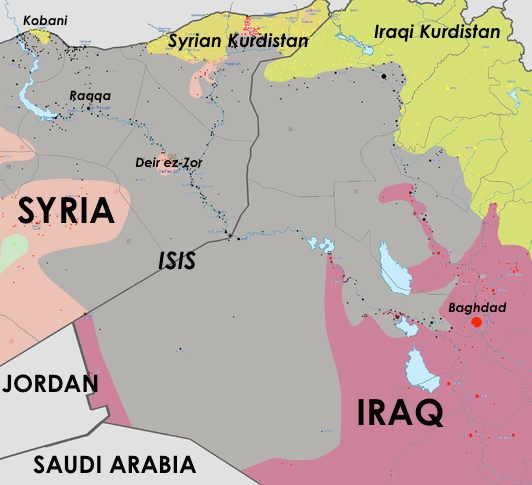

[Added at 3:30 AM EDT on July 25, 2015: And below is a zoomed-out map showing the same area drawn above, this time in red, but within the regional context.]

Regional View: July 24, 2015 projection of the perimeter of a potential Turkish occupation zone and U.S. no-fly zone in northern Syria. Click to enlarge.