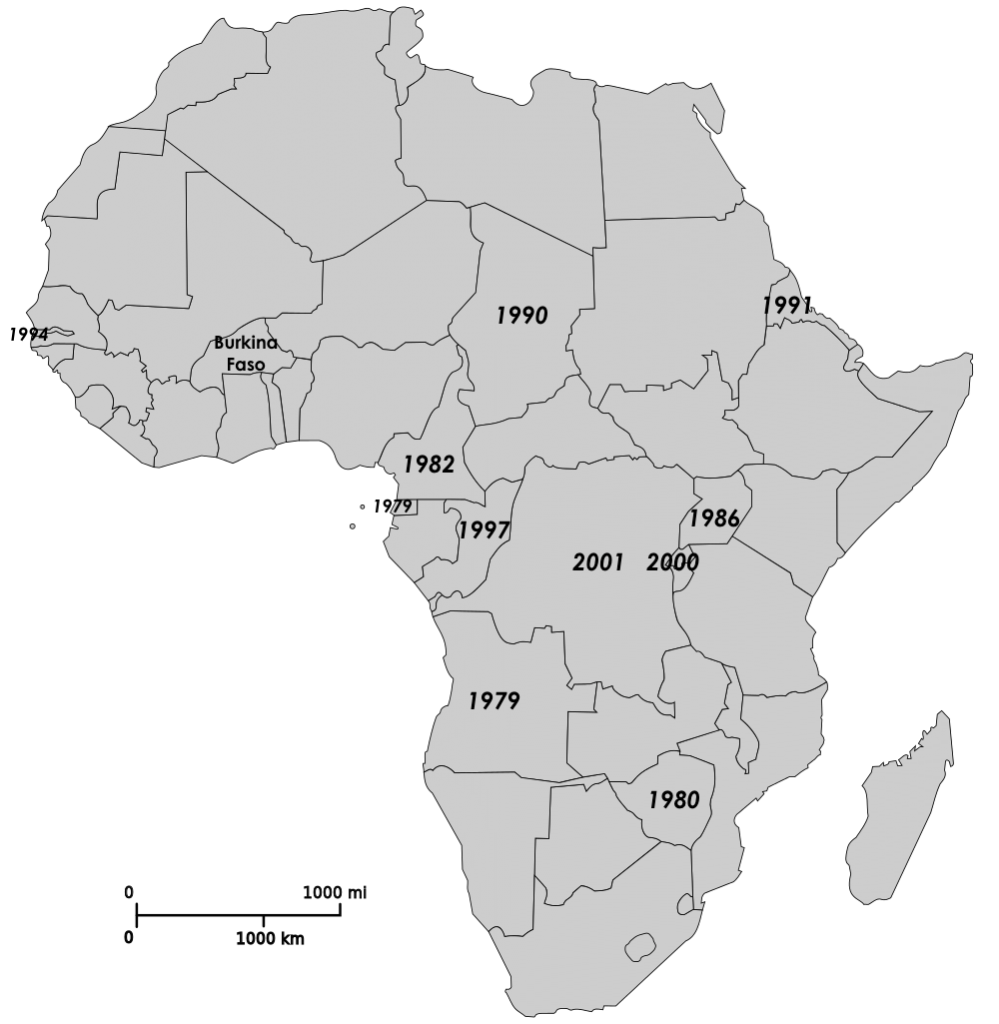

The 27-year West African regime of dictator Blaise Compaoré appears to be collapsing today in Burkina Faso. [He resigned and handed power to the military on October 31.] Here’s what you need to know…

Who is Blaise Compaoré?

President Blaise Compaoré seized power in a violent coup in 1987 (see Fast Facts) and planned to seek election a 5th consecutive time by amending the constitution.

There are literally close to three dozen opposition parties, which tends to keep them very weak. Compaoré, who lives in a ludicrously vast palace, was also the mastermind of the earlier 1983 coup and has killed off all his former compatriots in purges.

In early 2011, as regimes were collapsing across the world (including former patron Qaddafi), Compaoré survived a presidential guard mutiny over pay and protests across the country over the deaths of protesters at the hand of security forces. Riot police in the capital actually joined that uprising. A compromise with the military over the pay dispute regained their support and suppressed the protests.

He has been well liked by regional and international leaders for his work in mediating recent conflicts in Mali, Côte D’Ivoire, and Togo. Plus, until this week, the country was one of the most stable for almost three decades. Compaoré has been a key military ally of France in the Sahel and the United States in West Africa.

He has been well liked by regional and international leaders for his work in mediating recent conflicts in Mali, Côte D’Ivoire, and Togo. Plus, until this week, the country was one of the most stable for almost three decades. Compaoré has been a key military ally of France in the Sahel and the United States in West Africa.

Protests, however, have been bubbling under the surface over unresolved economic struggles for a year or so. Still, they did not erupt into full-scale pandemonium until this week.

What happened this week?

Tuesday, opposition protests in the capital — over a proposed constitutional amendment to remove presidential term limits, scheduled to be voted on at the parliament today (Thursday) — clashed with police and shut down traffic.

Today, the military was deployed into the streets of the capital. According to the BBC feed and reporting, protesters and sympathizers responded by:

– Seizing the state television headquarters and broadcast center

– Torching the ruling party headquarters

– Seizing the parliament building and burning it to the ground (no place to vote on the amendment now!)

– Looting a hotel where members of parliament typically reside when in the capital

– Burning the homes of several cabinet members

– Marching on the presidential palace

– Shutting down the airport and arresting the president’s brother there (presumably as he attempted to flee the country)

– In other cities, government buildings were also burned or looted and protesters clashed with riot police at street barricades and churches

At least five are dead, probably more. There were reports that some soldiers were standing down or actively assisting the protesters, while other photos showed them still pointing guns. Loyalist forces reportedly fired live bullets into the crowd and a helicopter dropped tear gas.

Some protesters have dubbed this uprising the “Black Spring,” either in ethnic comparison to the Arab Spring or in reference to the violence. (I’ll keep looking into that. Edit: From looking on francophone Twitter, the phrase is “printemps noir,” literally Black Springtime, used alongside and in comparison to “printemps arabe,” the French term for the Arab Spring. French Wikipedia also notes that “Noir,” in addition to being the color black, is the predominant ethno-racial identifier in the French language for any person of color from or descended from the darker-skinned populations of the whole of sub-Saharan Africa, which includes Burkina Faso. While the same word is also used for “dark” in the sense of dark humor or dark events, which led to my uncertainty, it is being used in the ethno-racial sense here.)

In a written statement, the president declared a nationwide state of emergency, dissolved the cabinet, called for peace and talks with protest leaders:

“A state of emergency is declared across the national territory. The chief of the armed forces is in charge of implementing this decision which enters into effect today. I dissolve the government from today so as to create conditions for change. I’m calling on the leaders of the political opposition to put an end to the protests. I’m pledging from today to open talks with all the actors to end the crisis.”

There was some dispute as to the validity of the statement, as it was hard to verify it had actually come from President Compaoré.

There is word that a popular retired military general, former Defense Minister Kouame Lougue, is meeting with the military’s current leadership and may be supported in a coup or transition government by the protesters. If a coup is in progress, this would be at least the sixth since independence, but the first since the end of the Cold War. However, a Reuters photojournalist on the ground, quoted by the BBC, said that many protesters view the current military leadership and soldiers as the protectors of the president and enforcers of the state of emergency; they might not be willing to support such a coup.

The Army announced there would be a transitional cabinet in place for the next twelve months until the 2015 presidential election. It was not clear if this meant Compaoré would remain in office until then under their plan.

Added: In an evening appearance on private channel Canal 3 reported by Le Monde, President Campaoré said he would not resign but would withdraw his proposed amendment to the constitution and step down at the end of his current term next year. I don’t expect that will be the end of it, because I believe he will be pushed out or forced to resign within days.

What was the global response?

The United States National Security Council statement:

The United States is deeply concerned about the deteriorating situation in Burkina Faso resulting from efforts to amend the constitution to enable the incumbent head of state to seek another term after 27 years in office. We believe democratic institutions are strengthened when established rules are adhered to with consistency. We call on all parties, including the security forces, to end the violence and return to a peaceful process to create a future for Burkina Faso that will build on Burkina Faso’s hard-won democratic gains.

This is a clear criticism of Compaoré’s bid to remove term limits but also leaves room to condemn the uprising if it proves to be the start of mass violence or a military coup.

The United Nations Secretary General dispatched its West Africa Special Envoy to the country, to arrive tomorrow, although it’s not clear how he will arrive, given the closure of the airport.

The government in France, like the United States, appears ready to throw their ally Compaoré to the wolves, having sent their ambassador to meet with opposition leaders.

Most significantly, the African Union, which typically backs incumbent leaders to the bitter end (out of self-interest), condemned the Compaoré government’s constitutional amendment proposal and suggested support for the protesters. The statement:

The Commission also urges the Government of Burkina Faso to respect the wishes of the people as well as the prevailing Constitution of the Republic of Burkina Faso. The Commission reiterates its commitment to zero tolerance on unconstitutional change of Government and respect for the rights of citizens to peaceful protest.

While explicitly discouraging a coup or popular overthrow, this statement is probably the most significant sign that this will only end with the president’s removal from power, one way or another. At minimum they will be supporting a voluntary resignation and transfer of power, if that can be achieved before something worse happens.

Burkina Faso Fast Facts

Read more

He has been well liked by regional and international leaders for his work in

He has been well liked by regional and international leaders for his work in