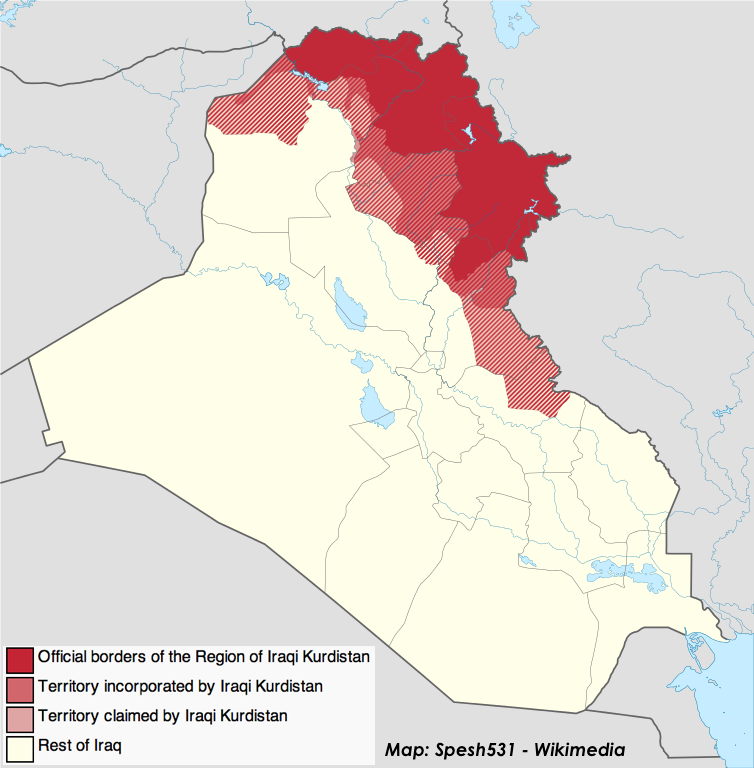

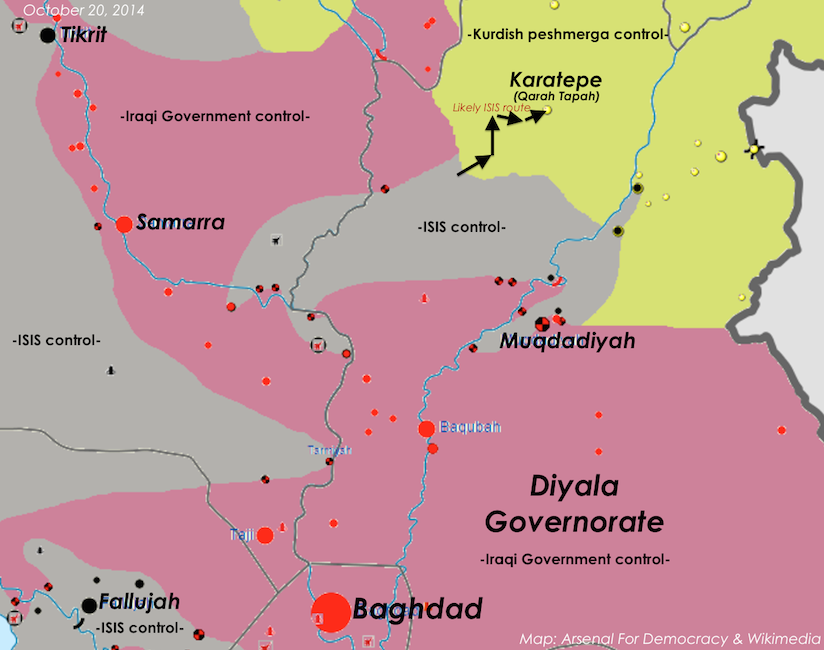

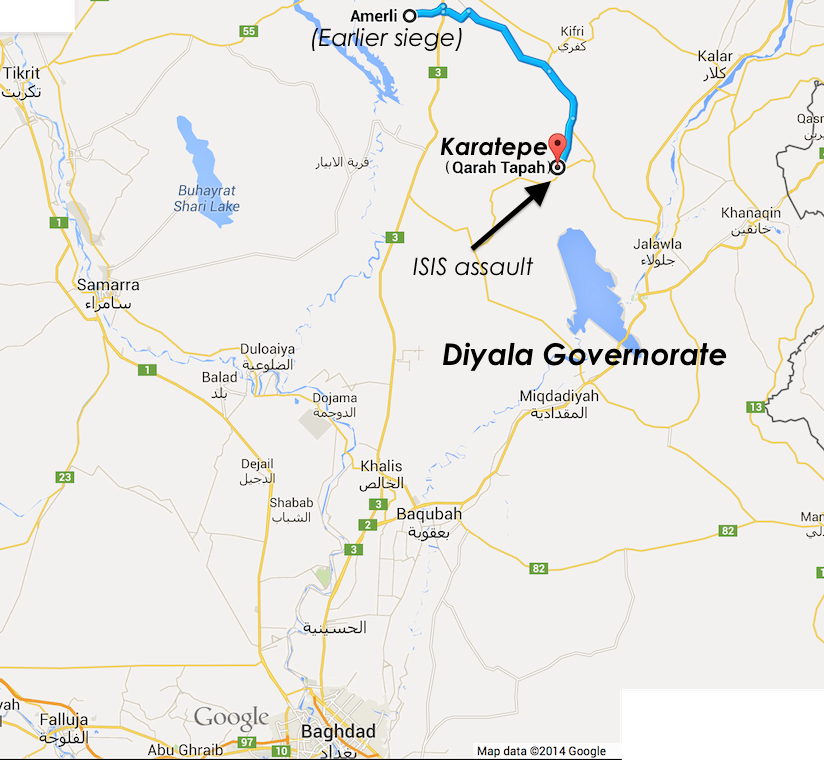

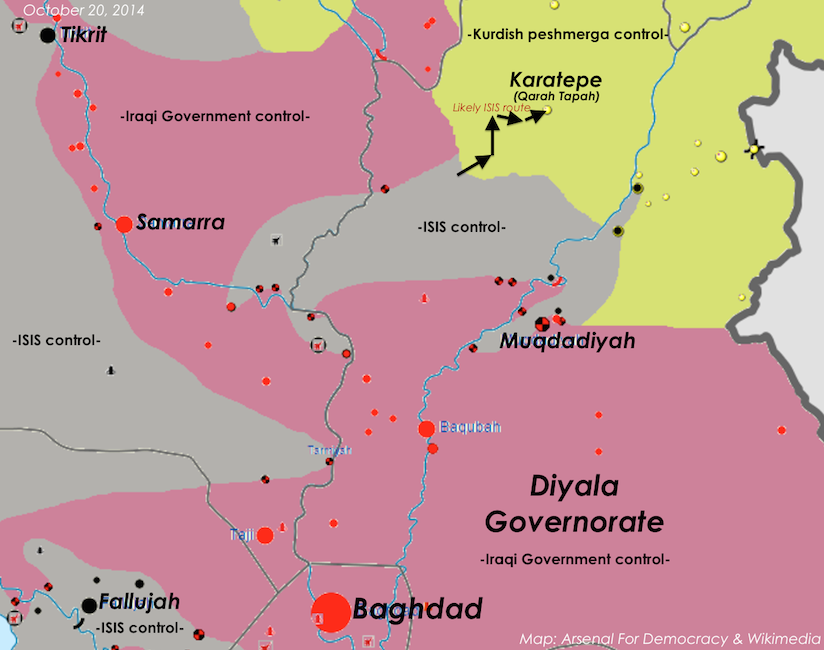

After U.S. airstrikes in August thwarted ISIS incursions into Iraqi Kurdistan from the northwest and broke the ISIS siege of the Amirli, a Shia Iraqi Turkmen town, a division of ISIS in the Diyala Governorate appears to have found a weak point in the armor on the southern side of the zone protected by the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG).

As a result of the June pullbacks by Iraqi security forces and the Iraqi Army, the KRG sphere of responsibility for security now extends south into Diyala, but their peshmerga troops are stretched thin against ISIS and are concentrated on retaking territory in northern Iraq.

ISIS forces staged coordinated attacks against Kurdish peshmerga paramilitary forces all around the Kurdish zone’s perimeter on Monday, October 20, according to a report by Rudaw, the Iraqi Kurdish news agency. Most of these were much further north in the country, however, than Diyala Governorate.

Karatepe under fire

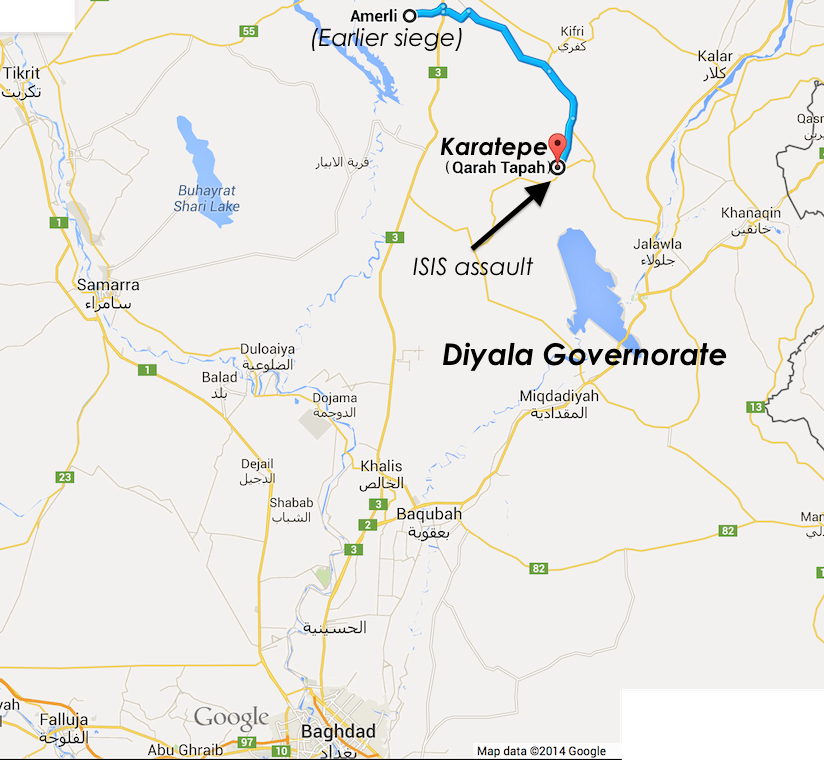

But an encircled group of ISIS fighters in Diyala took advantage of the large stretches of uninhabited and indefensible desert that make up the southern edge of Kurdish control to lead the day’s coordinated offensives by ferociously assaulting the predominantly Iraqi Turkmen community of Karetepe township, which they had apparently identified as vulnerable in a skirmish several days earlier and suicide-bombed the town the weekend before. (Karetepe is the local Turkmen spelling. It is generally spelled Qarah Tapah in Kurdish media and on Google Maps or Qara Tapa in English-language Iranian media.)

The lightly defended town came under heavy ISIS shelling and light arms fire, according to the Karetepe district leader, as reported in Rudaw:

The ISIS attacks began at the outskirts of Qarah Tapah, a town along Kurdistan’s south-western front also targeted by ISIS last week. Three Peshmerga were reported killed and others injured in an intense firefight, according to Mahmoud Sangawi, who is in charge of the district. “We repeatedly have been targeted with ISIS shells,” he said.

“They mean to take on the areas that are populated by Shia in order to carry out another onslaught on them,” Sangawi told Rudaw, referring to Shiite minorities who are living in villages around Qara Tapah.

“Islamic State suddenly began the attack in the early morning while most of people were asleep. They started bombarding the town but Peshmerga responded to their assault immediately,” a Qarah Tapah witness told Rudaw.

Peshmerga forces use intelligence resources to put their fighters on stand-by before an ISIS attack, but “the information this time seemed to be incomplete to guide us how to prepare for their attacks. They changed course and they attacked from different directions,” Sangawi told Rudaw after arriving at the frontline. “We will ultimately destroy them,” he said.

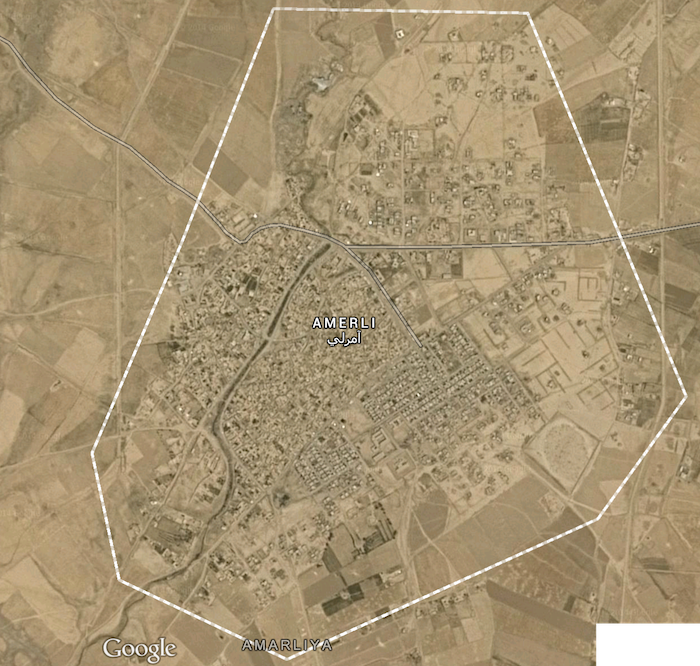

Cnes/Spot Image satellite photo of Karatepe (Qarah Tapah) township in Diyala Governorate. Diyala is an agricultural province with large farms and orchards surrounded by larger deserts.

On October 21, the pressure mounted, according to a report by Kerkuk.net, the official online publication of the Iraqi Turkmen Front, the party which represents the ethnic minority in Iraq’s politics.

Yesterday morning ISIS launched an attack from three directions on Karatepe township of Diyala with mortar and other heavy weaponry. The local people were forced to leave their homes due to the fierce conflict between security forces and ISIS militants. The number of dead and injured have not been determined so far. ISIS militants have seized the western entrance of the town.

Operations Command indicated that until now Karatepe town had been under the control of the Peshmerga and police forces. Operations Command also indicated that fighter aircraft had started targeting the ISIS militants.

Head of Iraqi Turkmen Front and Kirkuk Member of Parliament Erset Salihi called on all Iraqi Turkmen Front offices and organizations in Hanekin and Kifri in the periphery of Karatepe and instructed them to open their doors to refugees and give them necessary assistance.

According to Iranian state media, which favors the Shia-led Iraqi central government, “targeting” of ISIS attackers by “fighter aircraft” refers to assistance by the Iraqi Air Force. I don’t have details on that, but it would likely consist of barrel-bombing from the unsophisticated and generally inept Iraqi Air Force. No coalition airstrikes around the town have yet been reported.

On October 22, Iraqi Turkmen political leaders called a press conference to assert their view that this is a targeted offensive intended to destroy an Iraqi Turkmen population center and is part of a wider systematic purge:

The Head of Iraqi Turkmen Front and Kirkuk MP Erset Salihi spoke at the press conference and demanded the liberation of Karatepe township.

In his statement Salihi said that it was clear that today Turkmen areas were being targeted. After Telefer, Besir Tazehurmatu regions came Amirli. ISIS has started to target all Turkmen regions such as Tuz, Kirkuk, Tavuk. This time the target was Karatepe township in Diyala which is a major Turkmen settlement area. Kurds, Turkmen and Arab inhabit the region in harmony.

“As Turkmen MPs, we demand that air and land interventions are [begun] as soon as possible to ensure the security of those people and that they are armed so that they can protect themselves, their families as well as the land they inhabit.”

AFP reporting, quoting a source inside the town, implied that the population of the town and surrounding villages was at least 18,000 prior to the start of ISIS bombardment and civilians evacuations. An estimated 9,000 people left in the first day of fighting.

Late in the day on Wednesday, the Kurdish peshmerga forces and the Iraqi Air Force appeared to declare a preliminary victory in the battle, but it remains to be seen whether this is a temporary win or a decisive repulsing of the ISIS offensive.

Why here, why now?

Although the ISIS forces in Diyala Governorate are relatively cut off from the rest of ISIS, they draw on a deep well of local support. During the second crest of the Iraq War, after the U.S. surge began, many disaffected Sunnis, Sunni separatists, and Sunni insurgents made the province a major staging ground for attacks on eastern Baghdad, U.S. forces, and Shia Arab paramilitaries. By the time of the U.S. departure, the province had become a hotbed of Sunni resentment toward then-Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, whose autocratic Shia-led government is widely blamed for triggering the rise of ISIS within Iraq over the past twelve or so months.

Overall, the province is home to a more diverse population than those Sunni Arab extremists would like, which may explain the choice of target at Karetepe, as the political leaders suggested in their press conference. Besides its isolation in the desert making it an easier target, the town is home to a contingent of the minority Iraqi Turkmen ethnic group (learn more — jump to bottom), which ISIS has previously attempted to conduct ethnic cleansing on, all over the Iraqi Turkmen homelands. In the north, the minority has been driven out by the tens of thousands along with Yazidis and other minorities. Most prominently, however, Iraqi Turkmen were nearly starved out during the siege at Amirli, near the provincial border of Diyala, until coalition airstrikes and aid drops began. Having failed to take Amirli, 61 kilometers northeast by highway, Karetepe may be a next-best target for sectarian purgers in the Diyala ISIS faction. Indeed, it is actually even more diverse than Amirli, with Arab and Kurdish residents in addition to the Iraqi Turkmen residents.

If ISIS were to dislodge Kurdish forces and fend off Iraqi government forces and Shia Arab paramilitaries, they would be able to initiate an ethnic cleansing campaign in Diyala province that would make it much more strongly Sunni Arab in its demographics. This would likely boost the separatist aims of the Diyala autonomy movement that attempted in late 2011 to declare the province a “semiautonomous region” on par with the Kurdistan Region. (While that effort was joined by the province’s Kurds, the current war has unofficially absorbed most if not all of the Kurdish areas into the neighboring Kurdish provinces, so they would probably no longer be involved in the movement.) The autonomy backers were met with hostility locally from other minorities in Diyala. The Shia Iraqi Turkmen population at Karatepe and elsewhere in the area is generally somewhat more favorable toward Baghdad and Shia Arab governance than the Sunni Arabs or Kurds.

Another strong possibility is that the ISIS forces in Diyala will put enough pressure on Karatepe to force a significant diversion of troops and resources by the KRG, Baghdad, or Shia Arab paramilitaries that other ISIS positions will be strengthened and could regain ground. At the moment they have been pushed back out of the town and its immediate environs, but that may shift again.

Learn More: Who are the Iraqi Turkmen?

Read more