Human intuition seems generally unaware that time passes, instead viewing everything as being just as it always was. This is why we’re so surprised at how old we are looking in the mirror, and anxious thinking about our eventual deaths. It’s also why we say dumb shit like “Sunnis and Shi’ites have been fighting for thousands of years!”

Tag Archives: history

Justin’s Story: Hurricane Katrina’s 10th Anniversary – A Radio Documentary

Description: Justin recounts his evacuation from New Orleans in August 2005, what happened afterward, and what has happened to New Orleans in the 10 years since then. Running time: 1 hour, 2 minutes.

(Interstitial narration by Kelley. Produced by Bill. Recorded during August 2015 in Newton MA and New Orleans LA.)

Don’t forget to check out The Digitized Ramblings of an 8-Bit Animal, Justin’s video game blog.

(Image Credit: Vybr8 / Wikipedia) Caption: A merged derivative of two satellite photos of New Orleans. One was taken on March 9, 2004 and another on August 31, 2005 in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The middle frame of the three-image gif is a fabricated blend of the two source images.

Subscribe to our regular talk show:

RSS Feed: Arsenal for Democracy Feedburner

iTunes Store Link: “Arsenal for Democracy by Bill Humphrey”

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

AFD Micron #16

The origin story of minimum wage laws, part 2

Part 2: Why did some industrialized nations wait so long to get a minimum wage? When did the UK, Germany, and France get minimum wage laws? Why do some industrialized nations still not have legal minimum wages? || This original research was produced for The Globalist Research Center and Arsenal For Democracy.

Why did some industrialized nations wait so long to get a minimum wage?

From a historical perspective, minimum wage laws were implemented first in countries where trade union movements were not strong. Countries such as the UK that traditionally had strong labor unions have tended to be late adopters on minimum wage laws.

In those countries, powerful unions were able to bargain collectively with employers to set wage floors, without needing legislative minimums.

The early gold standard guideline for government participation in wage setting was the International Labor Organization’s Convention No. 26 from 1928 – although many industrialized countries never adopted it.

The convention said that governments should create regulatory systems to set wages, unless “collective agreement” could ensure fair effective wages. This distinction acknowledged that, by 1928, there was already a major split in approaches to creating effective wage floors: leaving it to labor organizers versus using statutes and regulators.

When did the UK, Germany, and France get minimum wage laws?

Much like pioneers New Zealander and Australia, the United Kingdom did adopt “Trade Boards” as early as 1909 to try to oversee and arbitrate bargaining between labor and management. However, its coverage was far less comprehensive than Australian and New Zealand counterparts and cannot be considered a true minimum wage system. Instead, UK workers counted on labor unions to negotiate their wages for most of the 20th century.

The Labour Party introduced the UK’s first statutory minimum wage less than two decades ago, in 1998, when it took over the government following 18 years of a Conservative government that had focused on weakening British unions. The country’s current hourly minimum wage for workers aged 21 and up is £6.50 (i.e. about $8.40 in purchasing power parity terms), or about 45% of median UK wages.

Despite opposition to minimum wages in some quarters, The Economist magazine noted recently that studies consistently show that there is little impact on hiring decisions when the minimum wage level is set below 50% of median pay. Above that level, some economists believe low-level jobs would be shed or automated, but this is also not definitively proven either.

In fact, not all countries with minimum wages above that supposed 50% threshold — a list which includes at least 13 industrialized economies, according to the OECD — seem to have those hypothesized problems. True, some of them do, but that may indicate other economic factors at work.

Germany, Europe’s largest economy, only adopted a minimum wage law after the 2013 federal elections. Previously, wages had generally been set by collective bargaining between workers’ unions and companies.

As a result of the postwar occupation in the western sectors, Germany also uses the “codetermination” system of corporate management, which puts unions on the company boards directly. This too encourages amicable negotiations in wage setting, to ensure the company’s long-term health, which benefits the workers and owners alike.

The new minimum wage amounts to €8.50 per hour ($10.20 in PPP-adjusted terms), or more than 45% of median German pay.

However, in some areas of Germany, the local median is much lower. There, the minimum wage affords significantly more purchasing power. In eastern Germany, the minimum is about 60% of median wages.

In France, where unions have long had a more antagonistic relationship with management, a minimum wage law was adopted much earlier – in 1950. It is now €9.61 per hour (about $10.90 in PPP-adjusted terms), or more than 60% of median French pay.

N.B. Purchasing-power currency conversions are from 2012 local currency to 2012 international dollars rounded from UN data.

Why do some industrialized nations still not have legal minimum wages?

Because of their generous social welfare systems, one might assume that the Nordic countries were early adopters of minimum wage laws. In fact, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Iceland all lack a minimum wage, even today.

Instead, wages in these countries are virtually all set by collective bargaining in every sector – conducted between workers’ unions, corporations, and the state. (This is known as tripartism.) Non-union workers generally receive the same pay negotiated by the unions.

A prevailing minimum or average lower-end wage can usually be estimated, but there is no law. In U.S. dollar terms, Denmark’s approximate lowest wage level is higher than almost every minimum wage in the world. Mid-level wages are even higher. Even McDonald’s workers in Denmark reportedly make the equivalent of $20/hour.

Missed part one? New Zealand, Australia, Massachusetts, the New Deal, and China: How governments took an active role initially, and how they balance economic variability now.

The origin story of minimum wage laws, part 1

Part 1: New Zealand, Australia, Massachusetts, the New Deal, and China: How governments took an active role initially, and how they balance economic variability now. || This original research was produced for The Globalist Research Center and Arsenal For Democracy.

More than 150 countries have set minimum wages by law, whether nationwide or by sector. Other countries have no legal minimum, or governments play a different role in wage setting processes.

Where in the world did government-set minimum wages originate?

In 1894, over 120 years ago, New Zealand became home to the first national law creating a government role for setting a minimum wage floor – although this may not have been the initial intention.

The Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act established an arbitration court made up of both workers and employers. It was intended to resolve various industrial-labor relations disputes in a binding manner. The goal was to avoid all labor strikes.

The court was empowered to set wages for entire classifications of workers as part of these resolutions. It did not take long for this to evolve into a patchwork of rulings that effectively covered all workers.

Today, New Zealand’s hourly minimum wage is about equivalent in purchasing power parity (PPP-adjusted) terms to US$9.40.

Which country first adopted a living wage?

In the 1890s, neighboring Australia was still a loose collection of self-governing British colonies, rather than one country. One colony, Victoria, was inspired by New Zealand to adopt a similar board with wage-setting powers. This occurred shortly before the Australian colonies federated together in 1901 to become one country.

In 1907, Australia pioneered what is now known as a “living” wage when the country’s new national arbitration court issued a ruling in favor of a nationwide minimum wage.

That court specified that it had to be high enough to fund a worker’s “cost of living as a civilised being.” While the ruling soon ran into legal trouble from the federation’s Supreme Court, it remained a crucial precedent in future labor cases.

To this day, Australia has a generous minimum wage. The current rate is about equal to US$11.20 in PPP-adjusted terms. This represents about 55% of median pay. However, New Zealand’s minimum wage is actually proportionally higher, at 60% of median pay.

N.B. Purchasing-power currency conversions are from 2012 local currency to 2012 international dollars rounded from UN data.

Which U.S. state had the first minimum wage?

In the United States, a minimum wage mechanism was first introduced in 1912 at the state level — but specifically for female workers (and some child laborers) — in Massachusetts.

The state passed a law to create a “Minimum Wage Commission” empowered to research women’s labor conditions and pay rates, and then to set living wages by decree. For any occupation, the Commission could set up a “wage board” comprising representatives of female workers (or child workers), employers, and the public to recommend fair pay levels.

The Commission’s decreed wage had to “supply the necessary cost of living and to maintain the worker in health.”

1912, the year Massachusetts passed the law creating the commission, was part of a period of major reforms in the United States, which had become the world’s largest economy.

These changes gave government a more active legal role in economic policy. In 1913, the country adopted the Sixteenth Amendment to the U.S. constitution, which made possible a federal progressive income tax. Also in 1913, the Federal Reserve System was created.

More than a dozen U.S. states followed Massachusetts within less than a decade. However, they had to contend with frequent battles before the U.S. Supreme Court on the constitutionality of government-set minimums. Read more

When The Party’s Over: The 1820s in US Politics

A recent eye-catching Washington Post op-ed, reacting to the surges of Trump and Sanders, posed the historically-based question “Are we headed for a four-party moment?” This op-ed had potential — it’s true after all that the seemingly solid two-party system in the U.S. occasionally has fragmented for a few cycles while a major re-alignment occurs — but, for some reason, it only used the 1850s and 1948 as examples (and 1948 isn’t even very illustrative in my view).

A far more intriguing additional parallel would be the 1820s (and the 1830s aftershocks). In 1820, one-party rule under the Democratic-Republican Party was fully achieved on the executive side of government, and no one opposed President Monroe for either re-nomination or re-election. It was the party’s 6th consecutive presidential win. The Federalists remained alive only in Congress, where 32 representatives (just 17% of the House membership) remained. By 1823, there were only 24 Federalists in the House. By the fall of 1824, they had all picked a Democratic-Republican faction to support.

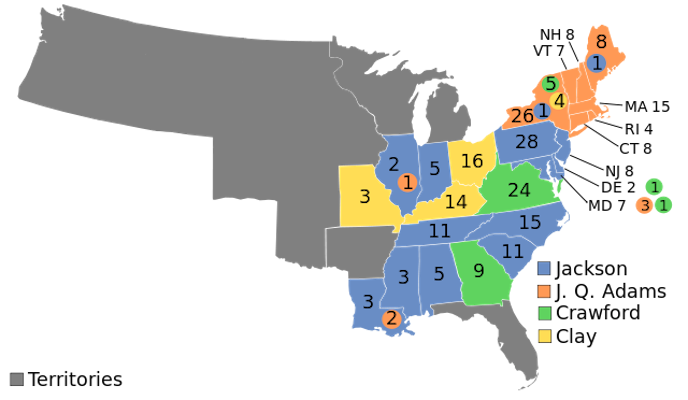

That year’s factionalism, however, was when things fell apart for single-party rule, alarmingly rapidly. The Democratic-Republican Party ran four (4!) different nominees and 3 running mates (Calhoun hopped on two tickets). Andrew Jackson won the popular vote and the most electoral votes, but no one won a majority of the electoral college. So, the U.S. House (voting in state-blocs under the Constitution) had to pick, and they chose Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, the second-place finisher.

1824 presidential election results map. Blue denotes states won by Jackson, Orange denotes those won by Adams, Green denotes those won by Crawford, Light Yellow denotes those won by Clay. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. (Map via Wikipedia)

In 1828, when Jackson set out to avenge his 1824 defeat-by-technicality, a huge number of new (but still White and male) voters were permitted to vote for the first time. Contrary to the popular mythology, not every new voter was a Jackson Democrat, though many were. To give a sense of scale for the phenomenon, both Jackson and Adams had gained hundreds of thousands of votes over the 1824 results in their 1828 rematch. At the time, that was so huge that the increases to each in 1828 were actually larger than the entire 1824 turnout had been.

In part as a result of all of this turmoil in the electorate, the party split permanently that year, creating the Democratic Party (which continues to present), under challenger Jackson, and the rival “Adams Men” trying to keep President Adams in office that year. The Democrats under Jackson won easily in 1828. A third party, the Anti-Masons, entered the U.S. House with 5 representatives.

The defeated Adams Men faction, having lost their titular leader, became the Anti-Jacksons — and were officially named National Republicans in 1830. That year, in the midterms, the Anti-Masons picked up more seats, to hold 17, while a 4th party (under Calhoun) of “Nullifiers” sent 4 representatives. But Jackson’s Democrats held a clear House majority.

The large influx of new voters also still needed to be managed, particularly by the opposition. The three big (or sort of big) parties in 1832 — Democrats, National Republicans, and Anti-Masons — held national conventions (all in Baltimore) as part of this democratization and party-organization push. Democrats, however, still clearly held an organizing advantage. Read more

The surge is a lie. A really dangerous lie.

The mythology of the Iraq War “surge” has been driving me bonkers for years — since at least as far back as 2009 or so, I think; I can’t remember exactly when I started getting into huge arguments with Republicans about it, but I remember a lot of arguments.

The surge was self-evidently a total failure even then, if you measured it by George W. Bush’s own stated objectives: suppress the violence long enough for a political solution to be reached.

As usual, like they did at every point in that war, the administration moved the goalposts to include only the first half (violence reduction) after the second half didn’t work (no political solution) — and many Republicans thus incorrectly believed it had been a success (because the violence was briefly suppressed). Unfortunately, it was an indivisible twin mandate, with the second being vastly more important and meaningful. Achieving the first part without the second can only be read as an expensive and bloody prolonging of the existing failure.

In a comprehensive article for The Atlantic entitled “The Surge Fallacy”, Peter Beinart makes the same point I’ve been making for years now — and extends out the hugely frightening consequences of the myth taking hold in place of the reality so quickly:

Above all, it’s the legend of the surge. The legend goes something like this: By sending more troops to Iraq in 2007, George W. Bush finally won the Iraq War. Then Barack Obama, by withdrawing U.S. troops, lost it.

[…]

In the late 1970s, the legend of the congressional cutoff [as a purported cause of failure in Vietnam]—and it was a legend; Congress reduced but never cut off South Vietnam’s aid—spurred the hawkish revival that helped elect Ronald Reagan. As we approach 2016, the legend of the surge is playing a similar role. Which is why it’s so important to understand that the legend is wrong.

[…]

In 2007, the war took the lives of 26,000 Iraqi civilians. In 2008, that number fell to just over 10,000. By 2009, it was down to about 5,000. When Republicans today claim that the surge succeeded—and that with it Bush won the war—this is what they mean.

But they forget something crucial. The surge was not intended merely to reduce violence. Reducing violence was a means to a larger goal: political reconciliation. Only when Iraq’s Sunni and Shia Arabs and its Kurds all felt represented by the government would the country be safe from civil war. As a senior administration official told journalists the day Bush announced the surge, “The purpose of all this is to get the violence in Baghdad down, get control of the situation and the sectarian violence, because now, without it, the reconciliation that everybody knows in the long term is the key to getting security in the country—the reconciliation will not happen.” But although the violence went down, the reconciliation never occurred.

[…]

The problem with the legend of the surge is that it reproduces the very hubris that led America into Iraq in the first place.

He then cites various harebrained Republican proposals to invade and occupy pretty much every country in the region based on the premise that the Iraq surge was a huge success and more troops = more success.

Less discussed perhaps is how President Obama, while taking much of the wrongful blame for “losing” a war that was already long lost in Iraq, seems to have managed to validate much of the mythology by trying to apply the surge approach (twice?) in Afghanistan with costly non-results.

But that ship has already sailed. In contrast, there is no need for the United States to make the same errors elsewhere going forward in the coming months and years. Misunderstanding what happened in Iraq after 2006 is likely to ensure a repetition of catastrophic mistakes.

Pictured: A December 2007 suicide car bombing in Baghdad during the surge. (Credit: Jim Gordon via Wikimedia)