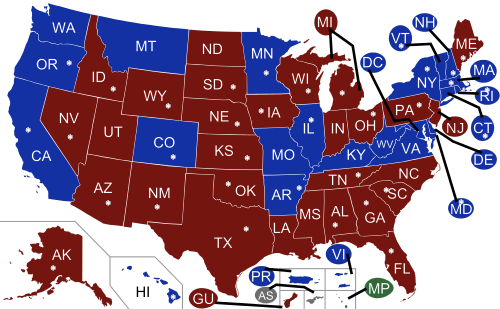

There are a huge number of races for governor up for election this year (which is true of any midterm year since most states adopted four-year terms aligned with the non-presidential cycle). 36 states — almost three-quarters of the states — will be electing or re-electing governors in November of this year, as you can see on the map below:

That’s a lot to take in. All of New England, most of the Mountain West and the Plains States, and so on. 36 states are on the board, and Republicans won a lot of them in the 2010 wave, which puts them in a good position overall, given the power of incumbency. But how do we analyze the state of the races more logically and clearly?

In the chart below, I’ve broken it down in an easy-to-read list form, with the states listed in either the Democratic or Republican column, based on current occupant (there are currently no independents in the state governorships). There are boxes around the retiring or term-limited current governors.

In that graphic, I’ve also put in italics the states that are most likely to be within reach. It’s not exhaustive, of course, just the likeliest. I based that determination — since I confess to being unable to keep up with all 36 races closely — on a) incumbent favorability from a year ago in the last Fivethirtyeight analysis I could find on the governors, and b) whether the voters have a solid preference for one party or the other in the governorship of their state.

In other words:

- a very popular incumbent is very likely to be re-elected (if running)

- a reasonably popular incumbent is pretty likely to be re-elected, even in a swing state

- a very unpopular incumbent is relatively likely to lose if running even in a solid state and could flip the office by negative association even if not running

- a state with a strong preference for one party in the governorship will likely not flip it to the other party whether or not the incumbent is running, even if quite unpopular

- but a state with a tendency to swing (or to elect a governor opposite to its overall preference) is somewhat more likely to flip an open seat to the other party

It’s a bit subjective and un-statistical, but it’s a good way to break down the problem when there are 36 races to analyze and too much data to crunch without being Fivethirtyeight or the like.

Using that assessment system, I concluded that there is a relatively narrow set of races that are fairly likely to be competitive come November.

Democrats’ biggest vulnerabilities — in my eyes — are Illinois, Massachusetts, and Arkansas. Let’s take those one at a time.

- Illinois: Gov. Pat Quinn (D) was an accidental governor elevated during the Blagojevich scandal. He won a very hard-fought race in 2010 to hold onto the office for his own full term. Now he is even more unpopular than he was in 2010, when he survived the Republican wave, and I don’t think the race is going well. That said, there’s very little recent data, and he’s come back from the brink once before.

- Massachusetts: Democrat Deval Patrick hung on in a 3-way race in 2010 but is retiring. Runner-up Charlie Baker (R) has generally been campaigning strongly in his repeat effort, while Democrats have fragmented between terrible, uninspiring, and unheard-of candidates. On top of this, Massachusetts has had a string of moderate Republicans between Dukakis and Patrick, with voters often seeming to prefer the office to counterbalance the single-party rule of the Democratic legislature. Dems may still hang on — indeed, leading contender Martha Coakley is currently polling well ahead of Charlie Baker (which means very little given her past track record and sketchy Bay State polling histories) — but the seat is very vulnerable.

- Arkansas: The state has Republican supermajorities in the legislature, has a term-limited Democratic Governor, Mike Beebe, who recently often seemed like the last Democratic oak standing in a Southern desert. The other windswept tree in the state, Sen. Mark Pryor, is in the political fight of his life right now. (I don’t have a good sense of how the Senate race will affect the governor’s race, if at all.) Dems seem to have a recruited a solid candidate to try to save the governorship, but it will be difficult. The RCP average has a close race, but the PPP poll within that average shows an 8 point advantage for the Republican.

Republicans’ biggest vulnerabilities — in my eyes — are Florida, Maine, Michigan and Pennsylvania. And now let’s take those one at a time:

- Florida: Rick Scott (R) is a terrible and very unpopular governor. Republican-turned-Democratic former Gov. Charlie Crist, his opponent, is far more popular and is polling relatively far ahead. Maybe Scott turns this around, but probably not.

- Maine: Paul LePage (R) is also a terrible and very unpopular governor, who is also (ideologically) a crazy person. He was only elected in a 3-way race in 2010, where the sane people made the mistake of splitting their votes between the other two candidates. Maine isn’t planning to repeat that mistake this year. Haha, just kidding: It’ll be a 3-way race again and probably a nail-biter to the end, between LePage and Congressman Mike Michaud (D). LePage is doing better (somehow) in polls more recently than he was for most of last year.

- Michigan: I am of the opinion that Gov. Rick Snyder (R) has been a horrendous governor for Michigan. He was, last year, almost as unpopular as LePage was in Maine. Democrats have coalesced behind a solid recruit, a U.S. Congressman, Mark Schauer. Nevertheless, Snyder seems to be a good campaigner with a lot of powerful friends (i.e. interest groups) and a ruthless agenda that the tea partiers love. He’s doing well in the polling, unfortunately.

- Pennsylvania: 2010 was a great year for Pennsylvania Republicans. However, Gov. Tom Corbett has been such a bad governor (and was dragged down further by the Penn State scandal) that he will probably be the first governor since the state allowed multiple terms in 1970 to lose re-election to a second term. These “unbroken precedents” in U.S. politics — most of which date back only as far as the 1970s — always tend get broken right after they’re declared ironclad. While researching this post, I saw some posts arguing that he will actually win. (Good fundraiser, incumbency precedent, his past big victories, past popularity before it tanked, etc.) But he’s trailing by high single digits in most polls at minimum and by double digits against several candidates in a lot of polls.

So there are about seven seats to watch right now. It might expand to 10 or drop to 5 as we get closer to November. My guess is that Republicans will lose a few of these seats — which isn’t surprising given how many they are defending — but will retain an overall edge and even pick up at least a couple. That basically means it’s probably going to be roughly a wash overall, without changing much nationally. I think that may be echoed in many of the other contests this year: Republicans will end up in about the same position they were when they started, but still ahead by a bit.

In addition to the much more contemporary mass slaughter of ethnic Chechens by the Russian Federation (and earlier waves of deadly internal deportations by the Soviet Union), there’s the simple, horrifying reality that the Sochi Olympics are being held pretty much at ground zero of a 19th century genocide/mass expulsion.

In addition to the much more contemporary mass slaughter of ethnic Chechens by the Russian Federation (and earlier waves of deadly internal deportations by the Soviet Union), there’s the simple, horrifying reality that the Sochi Olympics are being held pretty much at ground zero of a 19th century genocide/mass expulsion. One of the reasons we have a month set aside to celebrate and remember Black History is because unfortunately the teaching of American History tends to leave it out the rest of the time (which is also why there’s never been a need for a White History Month). However, just because it isn’t taught doesn’t mean it’s unimportant or that it doesn’t count. Here’s one historical event I want to talk about today because — sad to say — I only just recently learned of it myself.

One of the reasons we have a month set aside to celebrate and remember Black History is because unfortunately the teaching of American History tends to leave it out the rest of the time (which is also why there’s never been a need for a White History Month). However, just because it isn’t taught doesn’t mean it’s unimportant or that it doesn’t count. Here’s one historical event I want to talk about today because — sad to say — I only just recently learned of it myself.  A while back I posted the story of the experiences of the

A while back I posted the story of the experiences of the