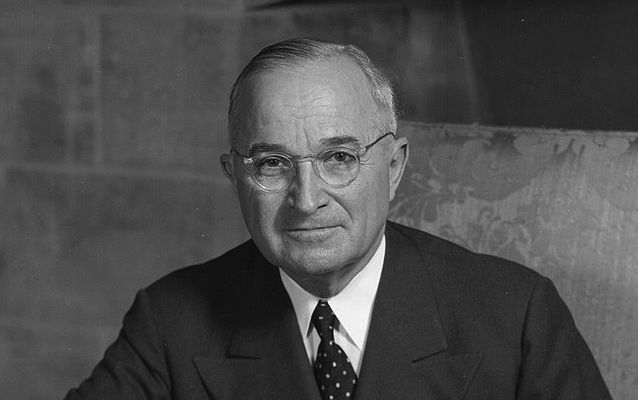

February 2006 Photo: President Mathieu Kérékou (right) of Benin receives Brazil’s president.

One of Africa’s most unusual and complicated leaders — Pastor Mathieu Kérékou of Benin — has passed away at age 82. The former radical military dictator and later civilian democratic president led Benin through several major transformations in its history, eventually earning him the surprising nickname “father of democracy.” BBC News:

Mr Kerekou had two spells as president totalling nearly 30 years, first coming to power as the head of a Marxist regime in 1972.

But he then accepted the idea of multi-party democracy and organised elections, which he lost in 1991. […]

He stepped down in 1991 after losing to Nicephore Soglo in a multi-party poll, but returned to power in 1996 having beaten Mr Soglo at the polls and then went on to win a second and final five-year term in 2001.

From 1972 to 1991, Kérékou served as the country’s military president, pursuing a radical new nationalism in his first two years and then a hybrid of nationalism and revolutionary Marxism-Leninism, backed by the Soviet Union. Much of it was marked by totalitarian violence and incompetent policy management. Over the course of his first presidency, the economic doctrines would grow less and less radically leftist and more moderate, eventually moving even to the center-right by the late 1980s.

During the early period, however, he renamed the country from Dahomey to Benin, in an effort to shed the French colonial legacies and avoid favoring one ethnic group over another, although both labels applied to pre-colonial African states in the area. Eventually, after facing down many coup attempts and amid growing economic stagnation and political unrest, he realized that his days were probably numbered if he clung to power — particularly with the Soviet Union’s fading influence and then disintegration — so he accepted a transition to multi-party democracy when it was demanded by a 1990 National Conference to fix the unraveling domestic situation.

Perhaps most importantly, however, Kérékou did not fight or cancel this transition when it became clear he would not be kept in power democratically, and he gracefully exited the political stage, even asking for forgiveness on national TV for whatever errors and crimes his regime had committed. He was permitted to remain president (albeit with an outside prime minister) through the 1991 elections, which he contested but lost by a landslide. 1991 in Benin became sub-Saharan Africa’s first successful direct handoff of power by a free election since the end of colonialism. This peaceful and stable transition likely helped spark or reinforce the coming wave of democracy in West Africa during the 1990s.

The onetime Marxist and atheist (rumored possibly also to have dabbled with Islam) staged an impressive comeback one term later, in 1996, this time as an evangelical Christian pastor, to become the second civilian president of Benin. This political comeback itself set its own precedent whereby former African military rulers would rehabilitate themselves as wise and experienced civilian candidates for the offices they once held by force.

Kérékou served two five-year terms as a civilian, from 1996 to 2006, before retiring again. Announcing, in 2005, his planned departure from the presidency per the constitutional term limits, Kérékou explained that a lifetime of high-level service had taught him one lesson many times: “If you don’t leave power, power will leave you.” Once again, he was strengthening democracy in Benin and the region.

His successor, President Thomas Boni Yayi, now nearing the end of his own second term had widely been rumored to be considering trying to remove the term limits provision but seems to have bowed earlier in 2015 to similar pressure to leave power before it leaves him. This decision to retire was likely reinforced by the Burkina Faso revolution in 2014 over an attempt to lift presidential term limits and the chaotic political violence in Burundi after the president sought a third term on a technicality. For now, the unexpected legacy of Kérékou, born-again democrat not totalitarian dictator, will live to see another day.