When Black people and other People of Color speak out about the lack of representation for them in any medium there is usually a lot of pushback. Replies range from pointing to the one example of non-White representation they can find, to the more extreme and exclusionary “If you want to be represented, make it yourself!” The latter is an interesting piece of advice, but it’s entirely too simple.

Moreover, it ignores the fact that Black people have for many years have been doing just that, only to then be punished for it. Throughout history, in instances where Black people in the U.S. tried to make their own place in society, they were met with extreme opposition.

In Memphis TN in 1889, because the success of his grocery store was taking Black customers away from the competing White-owned grocery across the street, Thomas Moss was lynched.

In 1923, the town of Rosewood FL, a primarily Black town, was destroyed after a rumor was spread that the town was housing an escaped Black prisoner. In both cases, and in many other instances of lynchings or any attack on Black communities, the Black victims were attacked because White people were uncomfortable with the idea of Black Success — or even Black Self-Esteem and Assuredness.

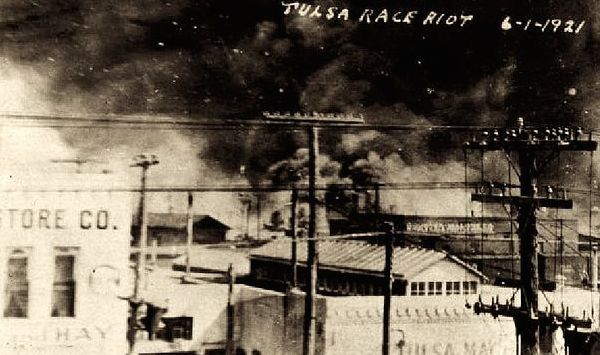

The bombing of Black Wall Street (otherwise known as the Tulsa Race Riot) is a textbook example of the results of this discomfort. In the early 1900s, the city of Tulsa began to grow at a rapid pace. By 1921, just after the first world war, the city was already going through its second oil boom.

The Black neighborhood of Greenwood, although not oil-rich, was prospering in its own right. Segregation meant that the Black residents could not patronize most place outside of the area, but they could own businesses, homes, and more in Greenwood. They did so, establishing good businesses by the hundreds. The neighborhood flourished and became a center of Black affluence, earning it the nickname “Black Wall Street.”

Then, predictably, in May 1921, there was a crime reported. A young White woman was assaulted, and the assailant was said to be a young Black man. The young man under suspicion was arrested and, shortly after the rumors of the events spread, a mob of angry and armed white men decided to take matters into their own hands. They were met by a counter-mob, of Black men, and then the confrontation escalated when shooting broke out.

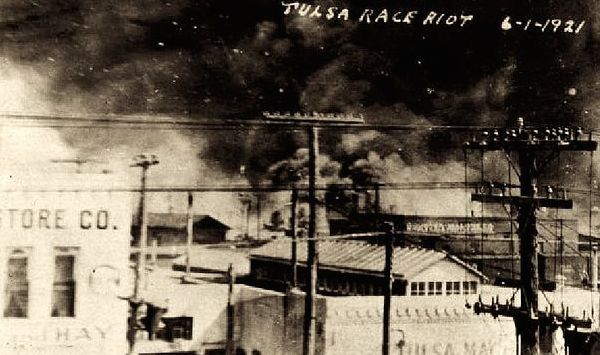

By the next morning, on June 1, Greenwood had been burned almost to the ground, and up to 300 people were killed. Residents even reported that planes had gone over the neighborhood and dropped crude bombs on businesses and residential buildings. Troops were deployed to try to restore order, but it was too late. The destruction left many of the residents homeless and living in tents for almost a year.

Postcard in the collection of McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa, showing the fires the day after the destruction of Black Wall Street. (via Wikimedia)

There is a lot of speculation on what the actual motivation behind the attack was. Although it was initially stated that it was because of the alleged (and later dismissed) attack of the young White woman, there was already high racial tension before then. White residents’ membership in The Ku Klux Klan had grown rapidly in the few years before the attack, and many of the White people in the Tulsa neighborhoods just outside of Greenwood were poor.

Seeing the neighborhood just next door doing so well probably made the already existing tension even worse. The initial accusation of an assault on a White woman by a Black man was a common trope in, and racist excuse for, lynchings or attacks on Black neighborhoods that were doing well economically in the South.

Whatever the motives behind the attack were, this is still a horrendous moment in U.S. history. Although the neighborhood was able to eventually rebuild itself over the next five years, it still goes to show that even when Black people are able to build their own communities, there is still the threat of people on the outside destroying everything.

Maybe instead of the emphasis just being on Black people “making their own” there could be an equal emphasis placed on others not destroying what we do make.