The bigger picture framing Nicki Minaj’s frustrated tweets about the VMAs.

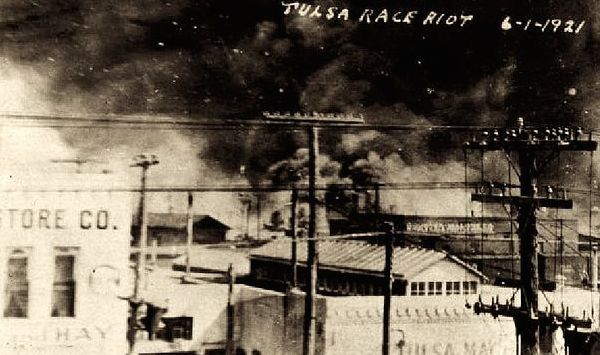

Nicki Minaj at the 2010 VMAs. (Photo Credit: Philip Nelson / flickr)

I’ve said before that there is an unwritten code of conduct that Black women must adhere to in order to be taken seriously, listened to, or even allowed to live.

Most other people will quickly claim it’s the attitudes of Black women that causes us to be dehumanized, but that is untrue. Even when we’re being polite, any disagreement from Black women is treated as aggression. So where and when are we allowed to speak up if we’re being mistreated, when everything we say is considered an attack?

On Tuesday, rapper Nicki Minaj took to Twitter to vent about the VMA nominations. Nicki is by far the most popular female rapper out there right now. She has found major pop success as well. But she has always been very vocal about how Black women in the music industry often don’t get the recognition they deserve for their work.

If I was a different "kind" of artist, Anaconda would be nominated for best choreo and vid of the year as well. ???

— NICKI MINAJ (@NICKIMINAJ) July 21, 2015

She’s no stranger to the way the public sees her (and other Black women) either, so in her tweets on Tuesday, Nicki Minaj states plainly her disappointment at her record breaking video for Anaconda being snubbed for Video of the Year. Nicki points out that although her video was a viral success, broke Vevo records, and was even parodied on the Ellen DeGeneres show, her video did not receive a nomination. She also points out that her video was a celebration of women’s bodies, but it seemed that this type of celebration was only acceptable on thinner artists.

Then this happened.

@NICKIMINAJ I've done nothing but love & support you. It's unlike you to pit women against each other. Maybe one of the men took your slot..

— Taylor Swift (@taylorswift13) July 21, 2015

Within the hour, articles popped up all over the internet about a “feud” between the two women, stating that Nicki Minaj had attacked Taylor in her tweets, even though Taylor Swift’s name wasn’t mentioned once, nor had Nicki been malicious towards other artists.

Nicki, in her own words, was pointing out where she saw how misogyny played a part in who was considered worthy of accolades and who was looked over. She was pointing out a complex problem in the most direct way possible. But it seemed that the media wanted to skip over her entire point and instead focus on a non-existent feud between the her and Taylor Swift.

Taylor Swift’s tweets did more than just derail a real and important point that Nicki Minaj was trying to make. Aside from being the most obvious case of a hit dog hollering, Taylor’s tweet demonstrated a huge issue that mainstream White Feminism has when it comes to dealing with Black women and other People of Color.

They don’t get that our experiences are different from theirs and often try an chastise us for perceived slights against them, while ignoring the real ones we face. Although Nicki Minaj’s tweets are a criticism of the VMAs, Taylor tries to make it seem as if Nicki is “pit[ting] women against women” for simply speaking about her experience as a thick and Black woman in the music industry.

Instead of understanding that Nicki’s experience as a woman is different from what her own might be, Taylor instead falls back to a very narrow — and White — view of what life is like as a woman.

Read more