The following essay also appeared in The Globalist.

On May 29, Nigeria experienced its first peaceful transfer of power between two elected leaders from rival parties. This is cause for celebration despite Nigeria’s recent hardships.

While it might not seem like it at this moment, Nigeria could also well be on the verge of its long-awaited global economic breakout.

View of Abuja, Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria, 2012. (Credit: Bryn Pinzgauer – Wikimedia)

Among the world’s major economies, Nigeria is now either the 20th or 21st largest national economy in the world (depending on who’s counting).

According to an analysis by PwC released in February 2015, Nigeria is expected to climb 11 places in the rankings by the year 2050. That would mark the single greatest projected increase for any top 20 economy over that time period.

It would also put Nigeria into the top 10 economies worldwide, ahead of Germany and just behind fellow oil producer Russia.

Yes, there are still problems

It is true, of course, that security concerns and corruption could pose challenges to Nigeria’s projected growth. The past year’s government scandals and the violence of the northern insurgency were very much on the minds of voters in the recent national elections.

It is also true that among the major emerging market economies, Nigeria currently ranks as the hardest place to do business, according to the World Bank. It stands at 170th out of all 189 states ranked.

The country’s new president, former General Muhammadu Buhari, has pledged to crack down on corruption and inefficiencies as a top priority.

While, as always in Nigeria, it remains to be seen whether he puts his words into actions, Buhari has at least the advantage of having been around Nigerian power politics for a long time. He will not be cripplingly dependent on inept “advisers” as his inexperienced, neophyte predecessor was.

If the country manages to turn the corner on some of its past ghosts, then there is nothing preventing Nigeria’s dynamic rise.

Ultimately, the demographics are simply too favorable to stop Nigeria’s economic rise altogether in the coming decades.

The very good news

The country, which is sub-Saharan Africa’s 10th largest by land area, currently has 183.5 million people. While that makes Nigeria the seventh most populous nation on Earth right now, it is expected to reach the third spot – ranking behind only India and China by 2050.

Nigeria’s population is slated to increase by nearly 257 million between now and then. That market size makes it an attractive destination in itself. It is also well positioned to become Africa’s business leader, given the dynamics of its entrepreneurial class.

Read more

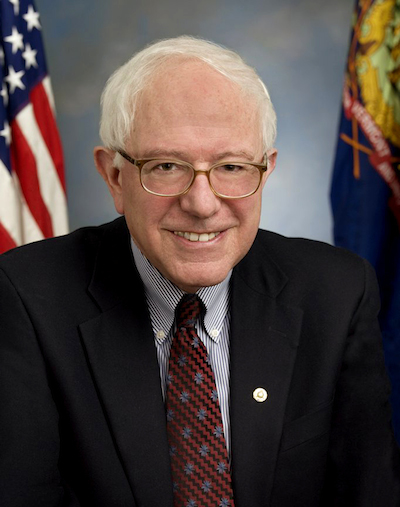

Senator Bernie Sanders has unveiled his latest policy proposal as part of his Democratic presidential campaign: Free public college, funded via a new financial transactions tax to discourage damaging Wall Street speculation. It’s a step up from his earlier

Senator Bernie Sanders has unveiled his latest policy proposal as part of his Democratic presidential campaign: Free public college, funded via a new financial transactions tax to discourage damaging Wall Street speculation. It’s a step up from his earlier