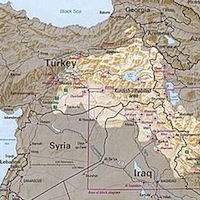

The New York Times this weekend published a “human interest”-type story on Ghassan Hitto — a longtime U.S. resident, Texas executive, and almost lifelong Syrian Kurd exile — who briefly became the first interim “prime minister” of the exiled pseudo-government of the Syrian opposition in Istanbul, Turkey.

My main takeaway from this article is that this story further supports the notion that not only is the Syrian opposition’s civil “leadership” (from the Syrian National Coalition to the “Syrian Interim Government” once headed by Ghassan Hitto) pretty much a complete joke with almost no experience in governmental functions, but it also has virtually no connection to events on the ground.

Whether the myriad rebel groups opposing the Assad regime were winning or losing the war, it made no difference to the so-called leaders drawn practically from everywhere but Syria. And they were so disconnected to the fighters that they never had any ability to influence them in the other direction either. They are — and have been from the start — utterly unrepresentative and irrelevant, yet have been more or less treated as the legitimate government-in-waiting by many (anti-Assad) government officials around the world.

It would almost be funny that this man, who had left Syria decades three earlier as a teen and still wasn’t back, at one point called himself “the prime minister of Syria,” if it weren’t so pathetic. Here are some excerpts from the Times profile:

Mr. Hitto, most recently the director of operations for a Texas-based telecommunications company, became interim prime minister of the Syrian opposition coalition a few days later. What was supposed to have been a two-week trip had evolved into something far more complicated.

Mr. Hitto, who had spent most of his life in the United States, had taken on the task of forming an alternative government to that of President Bashar al-Assad.

[…]

When people involved in the opposition government floated him as a candidate for prime minister, he was skeptical, he said. He had never before held public office. And the alternative government, based in Turkey and filled with expatriates, was still struggling to gain legitimacy.

[…]

His son Obaida was similarly reluctant to leave Syria, even though his father said that on the inside, he would become an immediate target for Mr. Assad’s men.

He questioned why his father wanted to work with the opposition coalition, voicing an oft-heard criticism among fighters and activists.

“I was in Syria where people were coming under shelling and didn’t have anything to eat,” Obaida recalled over Skype. “And there was the opposition coalition; people outside in hotels, smoking cigarettes.”

Though Mr. Hitto ultimately won over his son, who relocated to Istanbul to attend meetings with his father, the perception of the expatriate coalition as a collection of dilettantes and dreamers was one of the many obstacles he faced as he took office.

Back in Dallas, Mr. Hitto was known as a pragmatic community taskmaster, the man you put in charge to make sure the soccer field or mosque gets built. He had a history of activism, whether fighting for the legal rights of Muslims after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, or establishing a group in Texas to help Syrians in need.

But persuading the disparate members of his pseudo-government to agree on anything — while trying to win over rebel leaders who were skeptical of his background in the United States — proved to be impossible. He resigned after less than four months.

It brings to mind the bizarre coalition of embittered, one-upping, tough-talking Iraqi exiles (some of whom were hand-picked by the CIA a decade before) with almost no constituencies or followers left on the ground in Iraq, who managed to convince the (willingly hoodwinked) Bush-Cheney Administration in 2002 — against U.S. intelligence advisories — that Iraqis would uniformly welcome American troops as “liberators” and that assembling a new government would be easy-peasy-lemon-squeezy.

It’s amazing how often the governments of the world rush to proclaim some, essentially, randos with good sales pitches as the once and future kings of the countries whose governments they wish to change. The idea that leaders should have some sort of backing or base of support domestically seems like an alien concept to many.

In the case of Syria, this is just more evidence that there’s no point in the United States trying to support the “opposition” anymore, whether against Assad or against ISIS, because there isn’t one. And by more and more accounts from reporters, there probably never was a real one to begin with.