I think there are some pretty interesting parallels between the current wave of protests in Thailand and in Ukraine, as barricades are thrown up yet again in the capitals.

The central theme in both is a recurring cycling back and forth of two major political and economic factions under the same sets of leaders, reversed more by political upheaval than constitutionally-approved changes in government, without any sign of a permanent resolution.

In Thailand

After the 2006 military coup against the rural-backed, Red-led government, there was an uprising in 2008 by the Yellow faction and then another uprising in 2010 by the Red faction, which leads us to the current uprising (Yellow).

Commitment to democracy in Thailand is pretty low, in both the military and the urban middle class/business elites. (The latter are both generally aligned with the Yellow faction, against the Shinawatra family’s Red faction. The military and riot police tend to side with the Yellow faction but sometimes intervene against both sides.)

Then again, the Redshirt protestors in the capital’s downtown area in 2010 were basically attempting to lead an armed popular overthrow of the government and were only suppressed when the military decided to remain aligned with the Yellow-led government and cracked down. So, they’re no winners on the democratic values front either.

Now, it’s certainly not unheard of for political parties in developed democracies to have overt, semi-official, or informal party alignments based on class (middle class vs. populist poor) or geography (urban vs. rural and/or suburban), if not both. In fact, it’s probably the norm, if you look at the UK, Japan, France, the United States, etc.

But Thailand, which is still (clearly) not an established democracy, is probably taking the alignments a bit literally. That is despite the low likelihood that either side achieving total political control would result in any kind of social revolution of any serious depth.

But until they solve their political geography and class warfare problem — and until they get the military to stop intervening — Thailand isn’t going to break the endless cycle of totally unproductive but headline-grabbing popular uprisings. And for a country whose economy is heavily centered on tourism, the political situation for the last seven years has not been helpful to anyone.

Meanwhile in Ukraine…

I’m not going to comment on why Ukraine seems to capture more U.S. attention than Thailand, but it seems to. Anyway: Russian-aligned Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych recently ended efforts — initiated by his political opposition years ago and already on the skids anyway — to join the European Union, and announced plans to seek closer economic ties with Russia instead.

This triggered huge protests in the capital because the rival faction’s distaste for a foreign policy decision means it’s time to overthrow the government, again, it would seem. They are the largest protests seen since the late 2004 October Revolution.

I could well be wrong — and there are indeed a lot of dominoes falling inside his own government right now — but I suspect Yanukovych is secure in power, contrary to the excited Western reporting.

Ukraine has long been split between the pro-Russian side and the pro-European side (with high levels of animosity on both sides) and there have been plenty of protests on both sides with varying degrees of success since the USSR broke up in 1991. The pro-Russian side, largely concentrated toward the eastern end of the country, which borders the Russian Federation, is largely composed of ethnically Russian citizens, including President Yanukovych. They weren’t happy about the USSR’s collapse and fear(ed) reprisals.

The ethnic Russians fear reprisals because of the many terrible things the Russian Empire and especially the Russian-dominated Soviet central government perpetrated against the ethnic Ukrainian population, such as the Holodomor planned-starvation genocide under Stalin. The ethnic Ukrainian population is concentrated toward the western side of the country and has aligned itself with Europe, like many of the former Soviet satellites and postwar Soviet Republics (Ukraine is an interwar Soviet Republic).

So why is Yanukovych probably not going anywhere (or at least not anywhere far)? For one thing, it’s worth recalling right off the bat that while it’s true the last time we saw protests this big, in 2004, he was the one pushed to the side, the current protests exist because that uprising didn’t actually permanently get him out of the picture. If it had, he wouldn’t be in office now getting protested.

Much like the Thailand cycles discussed above, such is the rota fortunae of ex-Soviet Republic politics outside Russia: the same set of people cycling up and and down, facing Russia then Europe then back again. Lately we’ve seen the pro-Western/anti-Russian president of Georgia, who arrived in a parallel uprising in 2004, similarly finds his political fortunes fading as an opposing pro-Russian coalition rose to power. Other examples are strewn across the Central Asian ex-Soviet republics.

In Ukraine, it’s especially pronounced and more rapid. Current President (and target of protests) Viktor Yanukovych, as prime minister running for president, literally poisoned his opponent with dioxin in 2004 (see this 2006 photo of then-President Yushchenko’s face post-poison attempt), was kept out of the presidency by popular uprising, and then became prime minister again less than two years later. By early 2010 Yanukovych was elected president anyway, barely five years after the “Orange Revolution.”

But the second reason I don’t see him being flung from office is more specific to this situation: the Russians can do all sorts of things to bolster the Yanukovych government and blackmail the rest of the country into certain foreign and economic policy directions, while the EU can’t.

In contrast to the Russians, the European Union has offered very little and continues to be pretty powerless in helping the opposition. I have no idea what big plan they could suddenly float here, particularly given that Yanukovych is the democratically elected leader of Ukraine and, although repressive, isn’t just some guy who seized power and can be pressured from office. Unlike in 2004 when he tried to steal the election, he’s already in office, because he won. A lot of people don’t want him in office, but a lot of people definitely do. That’s the reality of the East/West split in Ukrainian politics and the citizenry.

Most of the EU’s offers to Ukraine are predicated upon Yanukovych first releasing political prisoners from his opposition, which isn’t going to happen by magic. Unfortunately, it’s not like they have much of a carrot or a stick to back that demand up, particularly since he never wanted a European alliance in the first place. Such demands only work when you have something the other person a) wants and b) can’t get elsewhere.

Now, as I said, I could be proven totally wrong here on the outcome of this latest round of protests, but the excitement of first-person POV camera phone shots doesn’t always translate to political reality.

And, even if Yanukovych falls from power again, he’ll probably be right back on top within 5 years. Ukraine won’t solve any of this for real until they solve their East/West Russia/Ukraine divide. The EU would probably me more useful to Ukraine if it made an effort to bridge this divide and bring everyone together so they can compete democratically and constitutionally for power, without endless recriminations and fear of sudden, repressive policy shifts one way or the other.

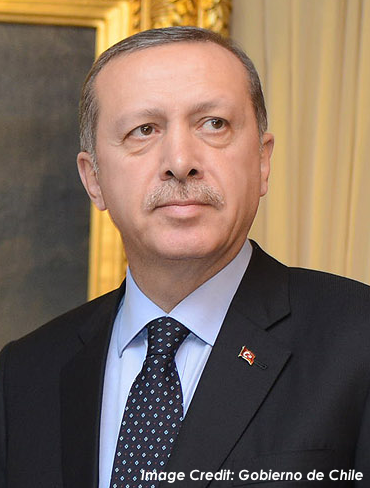

He has been well liked by regional and international leaders for his work in

He has been well liked by regional and international leaders for his work in

One man is alleging

One man is alleging  Another excellent article by Ta-Nehisi Coates (aren’t his always?):

Another excellent article by Ta-Nehisi Coates (aren’t his always?):